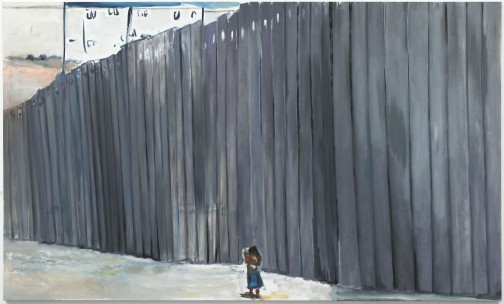

Figure in Landscape, 2009

I’m probably enjoying reading the legal filings in Craig Robins’ lawsuit against David Zwirner a little too much. [Randy Kennedy’s got a nice summary in the NYT today; basically, Robins says Zwirner revealed a confidential sale of a Marlene Dumas painting, which landed the collector on the artist’s blacklist, which Zwirner said he’d fix and didn’t, and that Robins could choose some Dumases from the current show, which he couldn’t.]

I’ve got no horse in this race, and I’m not a fan of Marlene Dumas’s work. [Though I admit it’s hard to consider it separate from the uncritical adulation that accompanied the outsized market hype of the last few years. And I did find some of these new paintings–including the three Robins said he wanted to choose from–admirably Tuyman-esque.]

What I am is fascinated by the language and the assumptions of collecting [and buying and selling] art that underpin it. The overly precise, legalistic argumentation of the filings reveals just how dependent many of the art world’s core interactions are on elision, subjectivity, and intentional ambiguity.

First, from the amended/updated version of Robins’ original complaint:

First, from the amended/updated version of Robins’ original complaint:

10. Thereafter in early 2005, defendants [i.e., Zwirner] breached Agreement I [i.e., the confidential sale a couple of months earlier in October 2004] by disclosing to MD that plaintiff [Robins] had in fact sold “Reinhardt’s Daughter,” [right] which defendants ultimate, apologetically and unequivocally admitted when plaintiff called defendants out on the issue. MD then immediately placed plaintiff on her personal “blacklist”, i.e., that plaintiff would not be able to buy any MD artwork in the Primary Market. Plaintiff’s placement on MD’s blacklist was and is a direct result of defendants breach of the confidentiality of Agreement I. [p.4, emphasis added to signal points of amusement]

This is clearly, awesomely Dumas herself. Zwirner had no need to “call Robins out” on the sale; he was a party to it. So at some point, within weeks or months of the deal, Dumas confronted Robins about secretly selling her work. His unequivocal apologies notwithstanding, he landed himself on “her” blacklist.

But Dumas is not actually named in the lawsuit, only Zwirner [and his galleries/legal entities.] So the artist herself is not a “defendant,” but the language of the complaint seems to indicate that at one point, Robins considered making her one. So while he sold work secretly through another dealer not the artist’s, and then abjectly–and, it turns out, unsuccessfully–apologized when she called him out, at some point in the last few weeks between drafting his lawsuit and filing it, Robins came to appreciate that suing an artist for blacklisting him was probably not the most effective way to get off her blacklist. I would count this as progress.

But onward. Part of the “irreparable damage” Robins is claiming is that he labored as a collector all this time–from 2005 until last month–under the faulty impression that he would be able to keep collecting Dumas’s work:

17. The unconscionable injury to plaintiff and plaintiff’s collection includes, in part, the works referenced below, which plaintiff would not have purchased to improve plaintiff’s collection, and enhance plaintiff’s reputation, and repeatedly exhibiting plaintiff’s collection featuring MD’s work.

Just remarkable. I really want to bold the whole thing. Robins details eight Dumas works he bought, presumably on the secondary market, and the hanging of Dumas’s work in a museum, his office, and his home, where, “during Miami Basel Art Fair, hundreds if not thousands,” of “major collectors” and “the public” tour and discover “who plaintiff is collecting, and who plaintiff believes in, which also is a big commitment by plaintiff to those artists.”

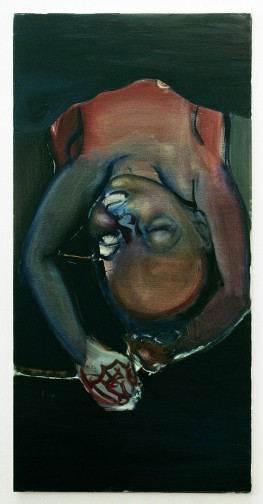

Under Construction, 2009

Robins also suffered “irreparable damage” because the blacklist

degrades and/or diminishes Plaintiff’s current collection and takes Plaintiff’s current collection off the list of frontier collectors of MD’s work and limits Plaintiff’s ability to have a full cross-section of MD’s work. [21, p.10]

Frontier collectors. Reinhardt’s Daughters was from 1994. Assuming he got it new [update: Ah, no. as Sarah Douglas reports, Tilton testified it was a secondary market piece. THIS is a transcript I’d like to see, your honor. -ed.] –Dumas’s output is typically characterized as low, and the work rarely came up at auction before the mid 2000s–Robins probably bought it, as “emerging art,” from Jack Tilton, the artist’s longtime New York dealer until 2008 when–here’s Zwirner talking to Deborah Solomon in the NYT about the wooing process and the switch:

It literally took four years before Marlene committed fully,” Zwirner told me, during which time he visited her in Holland on two occasions, met her in Venice on two others and assembled an ambitious show of her older works. In the end, Dumas was probably won over less by Zwirner’s charming attentions than by her affinity with the artists he represents. They include art stars like Luc Tuymans and Neo Rauch…

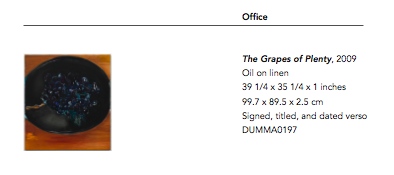

As for the deal and the sale, Robins told Zwirner his top three picks from the show: large-scale paintings of the wall Israel has constructed in the occupied West Bank. He was turned down, and instead, was offered “the right to purchase only (and no other work) MD’s most aesthetically undesirable work that is not even exhibited in defendants’ exhibition rooms.” [14, p.6] [That would be The Grapes of Plenty, 2009, which the Zwirner checklist shows as being located in the office. He then asked the court to prevent the sale of, “at a minimum, one or more of the Three Paintings” he said he’d like to choose from.

Which is a nice point to switch over to Zwirner’s filing, where he basically denies the existence of any agreement, and anyway, that’s not what they had agreed:

There is no “definiteness as to material matters” in the supposed verbal agreement to give Robins “first choice, after museums,” of “one or more” Dumas works. The alleged deal does not specify: (1) how may works Zwirner would sell to Robins; (2) at what price or price range the sale or sales would occur; (3) the duration of the agreement; (4) the time allotted to Robins to select or pay for a particular work or works; or (5) whether Robins would be given his “first choice” to buy whatever he wanted, or the “first choice” to buy a work or works selected by Zwirner. Under one reading, the supposed deal entitles Robins to buy one Dumas work, of Zwirner’s choosing, at a price set by Zwirner. Under another reading, Robins is entitled to buy every single Dumas work now on display at the current show, other than those acquired by museums, and may pay only what that [sic] he deems commercially reasonable – rather than Zwirner’s prices – while taking as long as he deems fit to make such payment.

“In such circumstances, the alleged agreement is void for vagueness: the parties failed to agree upon the essential terms.”…While Robins might protest that he and Zwirner made the agreement in principle in 2005, and that the details of piece(s), price(s) and timing would be worked out later, “‘a mere agreement to agree’ is unenforceable for indefiniteness where material terms are left open for future resolution.”…Indeed, the deal that Robins alleges is so “vague and indefinite that there is no basis or standard for deciding whether the agreement ha[s] been kept or broken.”…After all, Zwirner offered to sell Robins a painting from the current Dumas show – “The Grapes of Plenty” – but Robins declined the work.

Thus, besides the fact that Zwirner did not make the agreement, even if he had it would be unenforceable under N.Y. Gen. Oblig. Law, unenforceable under N.Y. U.C.C. and, moreover, void for vagueness. Robins has no likelihood of prevailing on his claims premised on this supposed agreement. [p16-17]

Here we have one of the most powerful dealers in New York, then, arguing that key elements of his business–because, come on, I think it’s clear that Zwirner gave Robins a Dumas assurance, and it had nothing to do with the extreme hypotheticals argued above–are entirely beyond the constraints and requirements of the laws governing business practice, and there’s nothing, legally, Robins can do about it.

Zwirner’s response also quotes Robins on the Dumas he was offered, calling it “close to last, if not the last, and least expensive choice” of the show. And “I would more accurately classify [this] as a glaring sarcastic insult than a work of art.”

The irony, of course, is that Robins is right on many of his counts. After selling Zwirner a significant early painting when the market was white-hot and works were hard to find, getting stiff-armed on the major Dumases and getting offered a decidedly minor work is an insult. And it would signal to some people that he’s not a “frontier collector” anymore, that he’s been cut out of the loop from the work he’d “supported” when it was new and cheap. But the insults don’t stop there:

Robins alleges that Zwirner promised to give him “first choice, after museums,” to buy “one or more” Dumas works shown at David Zwirner Gallery. Zwirner did just that: Robins was given the “first choice, after museums,” to buy “The Grapes of Plenty,” which is currently on display in the show. The fact that the work was not Robins’ “first choice” does not mean that Zwirner breached a promise to give Robins the “first choice” to buy a Dumas work. Undoubtedly, Robins believes that the supposed deal was to give him his first choice but such are the vagaries of verbal agreements. [p.17, emphasis, awesomely, in the original]

The conclusion of Zwirner’s motion is as stinging as it is disingenuous–and in just two sentences!

This is a suit brought by a wealthy plaintiff displeased that he cannot get what he wants when he wants it. He has offered nothing more than his own assurance that Zwirner made him a promise that, on its face, is absurd: a supposed pledge–when Zwirner did not even represent Dumas–that, if Zwirner ever did represent her and exhibit her work for sale, Robins would have “first choice, after museums” to buy “one or more” such works, without regard to price, quantity, competing buyers or duration of the purported promise. Perhaps most strikingly, there is not a shred of documentation–no contract, no letter, no fax, no e-mail, no text message, no nothing–reflecting either this alleged agreement or the equally ludicrous one never to reveal the sale of “Reinhardt’s Daughter,” a million dollar work of art with a new owner who can make his, her or its own judgments about whether to exhibit or publish the work.

Indeed, the buyer is not identified by either party. Zwirner’s filing says only that

On November 8, 2004, Zwirner facilitated the sale of the work to a Swiss gallery, which indicated that it would re-sell the work to a private Swiss client. The Swiss gallery paid $925,000 for the work, and Robins made a significant profit.

In March 2005, in the midst of a stunning 100-fold run-up in her auction prices fueled in part by actual speculator Charles Saatchi, a a show of Dumas’s older work opened in New York at Zwirner & Wirth, a joint venture between Zwirner and a Swiss gallery, Hauser & Wirth. Reinhardt’s Daughter was exhibited in the show–and published in its accompanying catalogue. Zwirner & Wirth dissolved their venture in 2009. The painting is currently listed on David Zwirner’s website.

[note: The Robins v. Zwirner case documents are available online via the US Courts PACER Case Locator. It’s Case No. 1:2010-cv-02787 in the 2nd District. Documents are $0.08/pg to retrieve, but thanks to an awesome Firefox extension called Recap, the public court documents someone else has retrieved are added to the Internet Archive and are made available to everyone for free. So, you’re welcome. If you are a PACER user, think about installing Recap yourself.]

post title: via a&w root beer

images all marlene dumas via david zwirner gallery