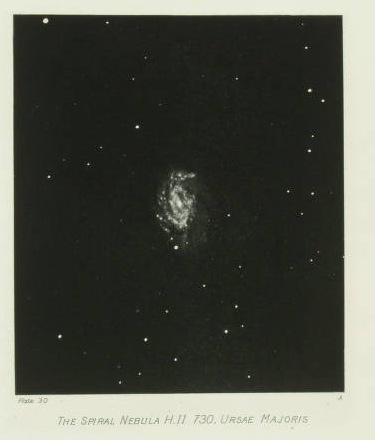

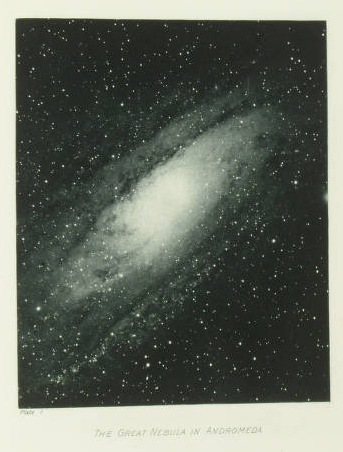

While wandering through the National Air and Space Museum [family’s in town], I stumbled across James Keeler’s lantern slides of spiral nebulae, taken at the Lick Observatory outside San Jose beginning in 1888.

Keeler was a pioneering astronomer at what was the largest reflector telescope at the first permanent mountaintop observatory in the world. He wasn’t the first astrophotographer [moon photos don’t count; everyone from Daguerre forward shot the moon], but he was a great one, and his deep sky photo survey is one of the earliest and most ambitious I’ve found. Keeler photographed hundreds of spiral nebulae and boldly estimated that at the rate he was finding them, there were at least 100,000 of them out there.

Three of his slides are on display at the museum. In the midst of what it called the “photographic fad” of 1890, The New York Times covered a lantern slide presentation Keeler made in December of that year at the New York Camera Club on Fifth Avenue. [Alfred Stieglitz joined the Camera Club soon after in 1891.]

Keeler’s slides, which he acknowledged were executed by a staff member at the observatory, were nevertheless described as “excellent in their make” and “some of the best specimens of star photography.” He went into great depth on the technical challenges of making telescopic photographs of the stars:

The usual method of keeping the star on the plate in photographing was by moving the telescope, but owing to the size of the instrument at the Lick Observatory this was impossible, as the telescope weighed seven tons. The plan adopted, therefore was to make the plate movable by means of turning screws.

…

…it happens that a different focus is obtained in the big telescope. The dry plate is therefore placed in the tube nine feet from the eye piece, a hole having been cut in it for that purpose…When the plate is developed the operator has to go it in a blind sort of fashion, as the smaller star images will not appear till the developing work is done.

…

Photographing stars, especially the small ones, is tedious work, as in some cases teh exposure must last for several hours. During all that time the plate or telescope must be moved so that the image of the star will continue in one place.

Keeler was the director at Lisk when he died suddenly in 1900, and his colleagues undertook to publish his sky survey and photos.

Photographs of NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS. Made with the Crossley Reflector was published in 1908 by the University of California. It contains 70 full page, hand-printed heliogravures [which is French for photogravures, which is actually French for any kind of photo-based printing technique, not just the copper plate-based intaglio-style prints associated with photogravure in English].

The Clark Art Institute has helpfully digitized all 70 of Keeler’s posthumously published plates. So far, I have not found information on the extent or state of his negatives, slides, or other prints. I imagine I’ll be digging into the Lisk and UC archives soon.