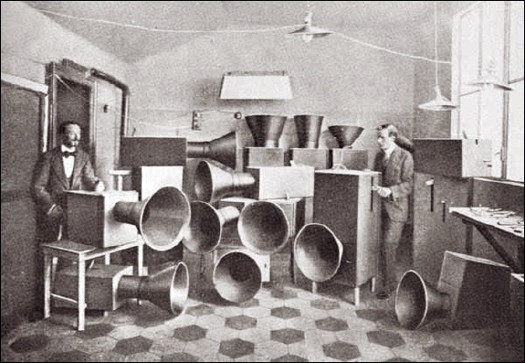

That’s Futurist painter Luigi Russolo on the left being helped by his friend Ugo Piatti, probably around 1913 or 1914. They stand amidst Russolo’s musical instruments, intonarumori, noise-intoners, which were designed in accordance with the principles laid out in Russolo’s Futurist music manifesto, l’Arte dei Rumori, The Art of Noise.

Though the trajectory of his ideas and influence is not quite as clear as The Hydra’s otherwise excellent recounting of his legacy imputes, Russolo was an innovator and visionary in the use of noise, found sound, in musical composition.

In The Art of Noise, Russolo makes a bold, lucid argument for music of the future to adopt the sounds of the world, especially the sounds of the machine, which had irrevocably changed the world’s aural landscape:

Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men. For many centuries life went by in silence, or at most in muted tones. The strongest noises which interrupted this silence were not intense or prolonged or varied. If we overlook such exceptional movements as earthquakes, hurricanes, storms, avalanches and waterfalls, nature is silent.

…

In the pounding atmosphere of great cities as well as in the formerly silent countryside, machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion.

Then there’s this, the source noise for his Intonarumori, the sounds of the modern world:

the gurglings of water, air and gas inside metallic pipes, the rumblings and rattlings of engines breathing with obvious animal spirits, the rising and falling of pistons, the stridency of mechanical saws, teh loud jumping of trolleys on their rails, the snapping of whips, the whipping of flags. We will have fun imagining our orchestration of department stores’ sliding doors, the hubbub of the crowds, the different roars of railroad stations, iron foundries, textile mills, printing houses, power plants and subways. And we must not forget the very new noises of Modern Warfare.

Indeed. Russolo’s first public demonstration of Intonarumori was in Modena in April 1913. An instrument called the scoppiatore variously called the exploder or crackler, it replicated the sound of an internal combustion engine, not, actual explosions. That would be the detonatore, which came soon after.

I realize that it was not mentioned specifically in Russolo’s list of noises, but how can you not think of hail cannon when you see that photo up there? Russolo was born in 1885 in the formerly silent countryside of the Veneto, which was at the heart of the hail cannon boom [sorry] at the turn of the century. Thousands of hail cannon were installed across the region in 1901-02; in 1904, the Veneto was the site of the first official scientific study of hail cannon’s effectiveness. [They failed, and once-enthusiastic farmers turned against them en masse and sold their hail cannon for scrap.]

Did Luigi perhaps recall a pastoral orchestra of hail cannonfire from his youth when he wrote his manifesto? I have no idea, but it’s interesting to think about. None of the intonarumori recordings on Ubu sound like the modern hail cannon these guys try to throw their Barack Obama basketballs into.

On an object note, Russolo’s original Intonarumori were destroyed or scrapped, but his nephew Bruno Boccato has refabricated some following his uncle’s original plans. I think these are they.