Christoph Brech is the master of the meaningful tight shot. In Sea Force One, he focuses in on a pair of workers in a small boat who are scrubbing the hull of Francois Pinault’s black yacht in front of Punta della Dogana during the 2009 Venice Biennale.

The work is included in “Portraits and Power: People, Politics & Structures,” at Strozzina in Firenze. It is interesting to compare their writeup of the piece–

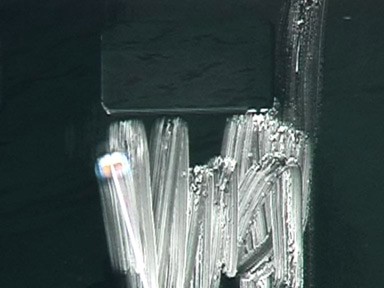

We do not know who was on board the yacht – possibly François Pinault himself, the famous French luxury goods entrepreneur and primary investor in the new Venetian exhibition area. Brech has turned his camera on a moment that would otherwise have gone unnoticed, deliberately choosing not to record the sumptuous affirmation of wealth of the yacht. It is the contrast between the size of the latter and that of the small boat, or between the black hull of the yacht and the evanescent white of the soap and of the reflections upon the water, that brings out the greatness of the vessel, the actual size of which we do not grasp. The artist succeeds in moving beyond the façade of power and wealth by stopping at its surface. He seems to be suggesting that the strategy for the construction of an image of power may lie in its antirepresentation: i.e., the “myth” of power is created by veiling or concealing the identity of those who hold it.

–with the artist’s own:

The yacht Sea Force One is anchored in front of a museum at the Punta della Dogna in Venice. The waves of the lagoon are reflected in the black varnish on the ship´s hull.

From a small boat nearby, workers are cleaning the yacht.

A painting emerges from the broad, white trails of foam on the ship´s dark surface, visible only for a short while until erased by cleansing streams of water.

Once again the reflected waves dapple the yacht.

At first read, I thought Brech’s focus on the formalist, painterly abstraction was notably less political than the Florentine curators’ interpretation. And damned if it doesn’t, in fact, look like a negative inversion of a making of film shot in Franz Kline’s studio.

Which immediately reminded me of the interview Felix Gonzalez-Torres did with Rob Storr, which I’ve reprinted and referenced here several times over the years.

I’m glad that this question came up. I realize again how successful ideology is and how easy it was for me to fall into that trap, calling this socio-political art. All art and all cultural production is political.

I’ll just give you an example. When you raise the question of political or art, people immediately jump and say, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, those are political artists. Then who are the non-political artists, as if that was possible at this point in history? Let’s look at abstraction, and let’s consider the most successful of those political artists, Helen Frankenthaler.

Why are they the most successful political artists, even more than Kosuth, much more than Hans Haacke, much more than Nancy and Leon or Barbara Kruger? Because they don’t look political! And as we know it’s all about looking natural, it’s all about being the normative aspect of whatever segment of culture we’re dealing with, of life. That’s where someone like Frankenthaler is the most politically successful artist when it comes to the political agenda that those works entail, because she serves a very clear agenda of the Right.

For example, here is something the State Department sent to me in 1989, asking me to submit work to the Art and Embassy Program. It has this wonderful quote from George Bernard Shaw, which says, “Besides torture, art is the most persuasive weapon.” And I said I didn’t know that the State Department had given up on torture – they’re probably not giving up on torture – but they’re using both. Anyway, look at this letter, because in case you missed the point they reproduce a Franz Kline which explains very well what they want in this program. It’s a very interesting letter, because it’s so transparent.

I guess it’s the curator’s job to overexplain things [?] but Brech’s title and his discussion of the work in terms of abstraction is plenty political in itself.