So much to blog, so little time. I may have to institute a new practice of dumping my interesting-looking browser tabs if I don’t write about or use them within a month, or blogging about them.

For example, ever since seeing a Le Corbusier manhole cover from Chandigarh sell for almost EUR18,000, I’ve been meaning to take this list of locations for Lawrence Weiner’s 2000 Public Art Fund project, and see which of his 19 downtown manhole covers looks the most lootable. But you know how it is with scheduling, holidays, pangs of conscience, snow, &c. &c…

So via Zelkova’s long essay on interactivity and digitization, I find this intriguing 2003 project, C & C, from the Lyon design studio Trafik. Joel, Pierre, and Julien all responded [merci, fellas!] to explain that C & C began as an exploration for a method to create designs for a handmade carpet. So they created a program in C that used the 3D coordinates of shapes created in Autodesk 3ds Max [above] to generate a 2D vector graphic [below].

Needless to say, I like the translational aspects of the project almost as much as I do the Dutch camo landscape-like polys.

One nice consequence of my recent Short Circuit research is seeing and reading up on Sturtevant. From Bruce Hainley’s Aug 2000 essay in Frieze:

As Sturtevant puts it: ‘Warhol was very Warhol’.

This is a complicated statement. How did Warhol get to be ‘very Warhol’? How does one come to recognise – see, consider – a painting, film , or anything by Warhol once he and everything he’s done are slated only to be ‘a Warhol’? It is Sturtevant who knows how to make a Warhol, not Warhol. It is Sturtevant who allows a Warhol to be a Warhol, by repeating him. Copy, replica, mimesis, simulacra, fake, digital virtuality, clone – Sturtevant’s work has been for more than 40 years a meditation on these concepts by decidedly not being any of them.

I’m kind of disheartened by how interesting Chris Burden’s post-minimalist undergraduate work sounds in this fully illustrated repro of Robert Horvitz’s Artforum cover story from May 1976 [volny.cz]

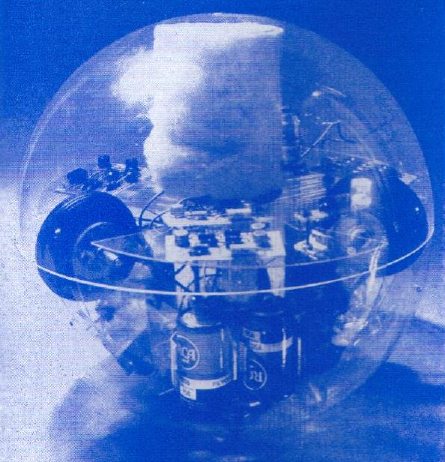

Via the awesome cyberneticzoo.com comes Toy-Pet Plexi-Ball a the 1968 artist/engineer colabo sculpture by Robin Parkinson and Eric Martin, which was included in Pontus Hulten’s MoMA show, “The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age.” The light-and-sound-activated Toy-Pet rolled around the gallery following viewers, until you put it in its fake fur bag. Which made it look like a tribble. Which can’t be a coincidence, can it, Pontus? If you have an engineer collaborating with an artist a year after the Star Trek episode airs?

Awesome kinetic/robotic artist James Seawright was one of the six artists–along with Aldo Tambellini, Thomas Tadlock, Allan Kaprow, Otto Piene, and Nam June Paik–who contributed to WGBH’s groundbreaking TV show/happening The Medium Is The Medium. Which is right in front of my face. And I’ve been staring at everyone but Seawright and Tadlock for a year. At this rate, I’ll be fawning over Tadlock sometime next summer.

Since my Google Street View Trike book project is entirely about the subject, I suspect I’ll keep Olivier Lugon‘s November 2000 Etudes Photographiques essay, “Le marcheur: Piétons et photographes au sein des avant-gardes,” open a little longer. Along with the Google translation.