Holy smokes, Richard Prince, Patrick Cariou, Larry Gagosian, Judge Batts, Bob Marley, Richard Serra [! I know, right?], Brooke Shields, $18 million in artwork, the fate of appropriation, the implosion of the gallery system, copyright apocalypse, there’s so much mayhem to discuss, where to start?

Let me cut to the chase here, and focus on the single most important takeaway of the Cariou v. Prince & Gagosian Canal Zone case: he won’t be suing me.

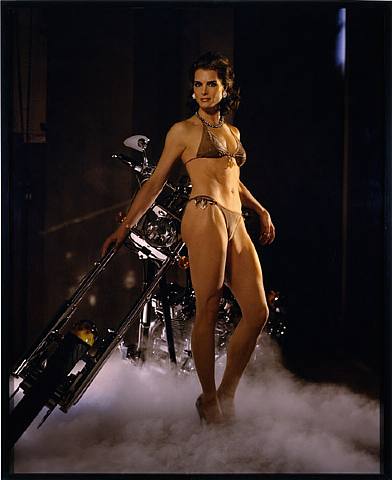

During a deposition, Cariou’s lawyer Daniel Brooks asks Prince about his 2005 work Spiritual America IV [above], for which he appropriated Sante d’Orazio’s photo of an adult Brooke Shields re-staging the 1975 Gary Gross photo of a 10-year-old Shields which Prince rephotographed and showed in 1983, in a temporary storefront gallery he rented on the Lower East Side and called Spiritual America:

Q. Do you know if Spiritual America Four is copyrighted?

A. No, I don’t know.

Q. Do you share the proceeds when it was sold with Mr. D’Orazio?

A. No. No, I don’t.

Q. You keep the proceeds?

A. When there’s a sale of this image, yes, it’s between myself and the dealer who sells it.

He was–I gave him a print.

I also gave Brooke Shields a print.

Q. She must have been appreciative?

A. I’m a, you know, agreeable guy..

Q. So getting back to, in Exhibit 6 where you said, However it would not bother me in the slightest–excuse me–for someone to appropriate my work.

A. Yes.

Q. Would that extend to Spiritual America Four?

A. Yeah. I mean I don’t–I don’t try to control those kinds of things.

Q. But I mean just you wouldn’t mind if somebody did exactly what you did–

A. They already have.

Q. You can scan it–

A. I saw it on someone’s screen–

[overtalking]

Q. You wouldn’t m ind if somebody sold Spiritual America Four, somebody else?

A. No.

Q. Without your permission?

A. They don’t need my permission.

Q. And you’re saying it has been done?

A. I don’t know whether they’ve been able to sell it. I haven’t been able to sell mine. Whether they’ve sold theirs, I don’t know.

Q. Well, you sold some of yours, right?

A. I sold some of mine, yes.

Q. And how do you know somebody else is trying to sell Spiritual America Four?

A. I’ve seen it. That’s the thing about technology, it’s what’s new, it’s what one has to adjust to. I’ve seen it on the web.

Q. And that’s fine with you?

A. It’s fine with me, yeah. I have no control over it. I mean, it’s their piece, not mine.

A. It’s their piece?

A. They’re putting their name on it.

Q. Who is they?

A. I don’t recall. I don’t know who the person is.

Q. Okay. So your view is if you create a work of art–do you consider this a work of art?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. If you create a work of art anyone else who wants to is free to copy it and sell it?

A. That’s the optional or the operative word you just said. Free.

Q. Right.

A. And art is about freedom. It’s not about being restricted. If I was restricted then I couldn’t transform these images.

Q. So but as far as you’re concerned, somebody else can just copy Spiritual America Four, make no changes to it, and sell it, and that’s fine with you?

A. Yes, that’s fine with me.

Q. That’s part of your artistic philosophy?

A. I believe that, yes.

Q. Does it matter if the person copying your work is an appropriation artist or does it not matter, can anyone do it, as far as you’re concerned?

A. There have been people who are known as appropriation artists who have done what I’ve done because of what I did.

Q. Right. But let me ask you this. Do you feel that because you are known for appropriating the work of others your reputation itself entitles you to engage in that artistic practice?

[Prince & Gagosian’s lawyers both object]

A. Reputation is a tricky word.

Q. Well you have a reputation for borrowing, appropriating things from other people, right?

[Objections]

A. My intentions were never to make myself a reputation. It was always–my intentions were always to make great art.

Q. Okay. But you are aware that you are known as somebody–prominently known as somebody who appropriates work of others?

[Objections]

A. I am told that, yes. I don’t necessarily acknowledge it.

Q. And whether you are or not, you don’t feel that your reputation for that practice has anything to do with your right to do it, your freedom to do it, right?

[Objections]

A. I don’t understand the question.

Q. I know. It was badly worded. You said before, you think people are free to take the work of others, copy it, and sell it, right?

[Prince’s lawyer objects]

A. I believe artists–

Q. Artists?

A. –should be as free as possible, yes, in their studios.

Q. And does it matter if those artists are known for the practice of appropriating or not?

[Prince’s lawyer objects]

A. It could be an art student. I would encourage it.

Q. Okay. I understand.

Spiritual America IV may have been a bad example for Brooks to cite. It’s a rare case where Prince actually collaborated with D’Orazio to make the work instead of rephotographing one. He asked D’Orazio to arrange the shoot for him. Another image from the series is on the cover of D’Orazio’s own monograph, Barely Private. Which may be part of the reason why the AP of Spiritual America IV didn’t sell for the Princeian estimate of £400,000-600,000 that Phillips put on it in July 2009.

[from pp. 117-123, Richard Prince’s deposition conducted Oct. 6, 2009, excerpted and filed May 14, 2010 as part of Prince’s motion to dismiss the case against him. Here’s a PDF (3.6mb), 1 of 2 submitted with this filing.]