Paddy and her commenters have already done a pretty good job sorting through the decision in the Cariou vs. Prince & Gagosian case, and there are other folks out there with far more expertise and time than I who are also weighing in.

And while I still think this case is really troublesome for the whole fair use ecosystem as it applies to the art world–or more specifically, to artistic practice–that effect may not be lasting or widespread. Fair use and transformative work are still messy, ambiguous principles, almost by design, and artists are gonna do what artists have to do. And really, Judge Batts’ decision is so poorly constructed, and ignores or misconstrues so many basic facts of the case, that it can’t hold up to the inevitable, coming scrutiny, much less serve as any kind of practical impact going forward.

Still, it’s so awful, I can’t let it go without calling out a few of the most egregious passages, arguments, and errors. So here goes.

1) Cariou’s Photos Are Copyrighted. NO $#%ing DUH.

This is the first section of Judge Batts’ decision, and it has gotten a lot of media mention from the skimming crowd, even though it seems utterly and entirely irrelevant to anything at all. [p.10]:

Cariou’s ownership of a valid copyright in the Photos is undisputed. However, Defendants assert that Cariou’s Photos are mere compilations of facts concerning Rastafarians and the Jamaican landscape, arranged with minimum creativity in a manner typical of their genre, and that the Photos are therefore not protectable as a matter of law, despite Plaintiff’s extensive testimony about the creative choices he made in taking, processing, developing, and selecting them.

Unfortunately for Defendants, it has been a matter of settled law for well over one hundred years that creative photographs are worthy of copyright protection, even when they depict real people and natural environments.

I have looked, and I cannot find any documents where Defendants actually made this ridiculous claim that Cariou’s photos–arty, black & white, published in a book–are not copyrightable. It’s like the stupidest tumblr excuse ever [I found this image on the Internet, so it must be public domain!], not the argument the copyright lawyer for the most powerful art dealer in the world would make. Why is this even in here?

Look, the closest argument/evidence I could find is an exhibit [Doc. 61-1] rounding up dozens of Google Image searches for Rastas and Jamaican jungles and ganja tours, but that was to counter Cariou’s inference that the only way to take pictures of Rastas is to do what he did, and live with them for ten years. [Which, according to his deposition, it turns out he didn’t do, But whatever.]

Wow, is it really 12:30? I’ve gotta get some sleep. OK, we’re back. And what follows is, by any measure, too long.

2) I Want Exhibit A

Exhibit A, aka the Composite Exhibit, is an apparently comprehensive, illustrated catalogue of all Prince’s Canal Zone paintings; with the images Prince used in each one, from Cariou’s Yes, Rasta book and elsewhere. It is not online. [All these documents are available for purchase at www.pacer.gov. Just search for Cariou to find the case (no. 1:08-cv-11327-DAB). If you regularly purchase copies of public court documents through pacer.gov, consider installing Recap, the Firefox add-on which checks to see if the documents you’re looking for have already been downloaded by someone, and are available for free. It also adds copies of the court documents you buy to resource.org’s growing, free and open archive. Anyway.] Two thirds of Prince’s 27-pg motion to dismiss the suit is taken up by details of the changes, techniques and processes that went into each of the 28 Canal Zone paintings.

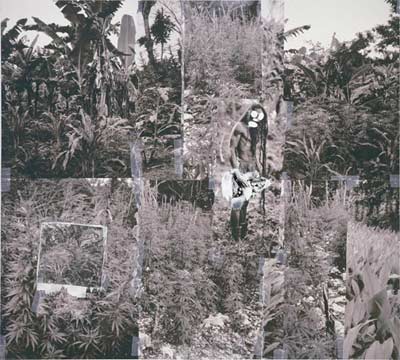

“Richard Prince, Canal Zone, 2008, 107 x 119.5 inches” with source images from Patrick Cariou’s 2000 book Yes, Rasta [via doc 54-24 in Cariou v Prince]

Here is one:

Canal Zone, 2008 In creating Canal Zone 2008 I used the same image that appears in Graduation and Meditation, but once again, I replaced the guitar with a different one and affixed different hands instead. In this painting, the Rastafarian is cut out and placed among the grid-like landscape, which is created from torn, scanned, altered, and reassembled images of foliage I took from various pages in Yes Rasta and, if I recall correctly, may include portions from a book on Tahiti I had come across. I used the photographs of different landscapes because I wanted the painting to appear like a camouflage backdrop, with the guitarist in the midst of lush foliage that has taken control of my fictional island. I also was inspired by Andy Warhol’s camouflage paintings, and his use of grids, so in this respect, I paid homage to him. The Rastafarian in the painting symbolizes a musician who is a solo artists, and is actually a reference to musician Neil Young (deliberately using a black man as a stand in for Young). He is holing an appropriated image of Neil Young’s guitar with proportional hands, and I added a white lozenge facemask as a reference to Picasso. Absent from this painting is any architecture or buildings to create a sense that nothing has survived after the apocalypse, except this man and his guitar and music.

Here, in depositions, in exhibits, there are literally hundreds of pages of testimony and evidence like this. If it sounds banal or pedantic laid out so explicitly, it nonetheless sounds entirely plausible and valid. At least as valid as any art can be that attempts to answer the non-burning question, “What if the world destroyed itself right now, while we’re sitting on the deck of Roman’s yacht in St. Barth’s?”

3) The definition of transformative use of the day:

[Quoting another case quoting Leval, whose article turns out to be the “foundational” argument for “transformative use,” who knew?] “The central purpose of the inquiry into the first factor is to determine, in Justice Story’s words, whether the new work merely supersede[s] the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with the further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.'” [p.14]

…

The cases Defendants cite for their proposition that use of copyrighted materials as ‘raw ingredients” in the creation of new works is per se fair use do not support their position, and the Court is aware of no precedent holding that such use is fair absent transformative comment on the original.

……[A]ll of the precedent this Court can identify imposes a requirement that the new work in some way comment on, relate to the historical context of, or critically refer back to the original works. [p.16]

The “raw materials” term comes from Blanch vs. Koons, a summary judgment which was affirmed by Judge Batts’ own Second Circuit court in 2006. On AFC, JD Hastings says that summary judgments don’t function as binding precedents. If that’s the case, all Prince’s lawyer’s efforts were for naught, which sucks for them. But on the bright side, all Judge Batts’ restrictions and omissions aren’t binding on anyone else, either. Is this really how fair use works, that every judge gets to make up the definition from scratch every time a case comes to court? That is insane.

4) But Judge Batts decided that Prince did nothing and meant nothing. Or worse.

Even by her own reductive definition above, Prince’s paintings could easily be found to be transformative use. But then this: “The Court therefore declines Defendants’ invitation to find that appropriation art is per se fair use, regardless of whether or not the new artwork in any way comments on the original works appropriated. Accordingly, Prince’s paintings are transformative only to the extent that they comment on the Photos; to the extent they merely recast, transform, or adapt the Photos, Prince’s Paintings are instead infringing derivative works.” This position really drives the rest of her argument. And leads to paragraphs such as this:

Prince also testified that his purpose in appropriating other people’s originals for use in his artwork is that doing so helps him “get as much fact into [his] work and reduce[] the amount of speculation” RP Tr. at 44. That is, he chooses the photographs he appropriates for what he perceives to be their truth–suggesting that his purpose in using Cariou’s Rastafarian portraits was the same as Cariou’s original purpose in taking them: a desire to communicate to the viewer core truths about Rastafarians and their culture.

Never mind the key distinction Prince made consistently and Batts never does between “images,” i.e., pictures in a book, and “Photos” and “originals” [!]. Presented with the works themselves, and reams of testimony about people stranded on an island after a post-apocalpytic collapse of civilization, with nothing but music, Batts decides that has absolutely nothing to say about Cariou’s romantic Rasta photos, or their historical context, this is what Batts comes up with: that Prince is basically doing exactly what Cariou did. Except that Prince was painting, not photographing. He was making paintings about photography, and its built-in assumptions of “core truths.”

5) And all this applies to every single Canal Zone painting.

Some of the paintngs, like “Graduation (2008)’ and “Canal Zone (2008),” consist almost entirely of images taken from Yes, Rasta, albeit collaged, enlarged, cropped, tinted, and/or over-painted, while others, like “Ile de France (2008)” use portions of Yes, Rasta Photos as collage elements and also include appropriated photos from other sources and more substantial original painting. 6

…

6 In reaching its determination herein, the Court has examined fully the exhibits and reproductions provided by the Parties and has compared the 29 Canal Zone paintings iwth the Yes, Rasta Photos. The Court sees no need to describe each work in great detail.

Or to consider it, even. It turns out Batts does acknowledge Prince’s alterations and process, but she considered them entirely irrelevant to the question of transformative use. And a painting that “consists almost entirely” of whole, appropriated images is as infringing as one that only “uses portions” as “collage elements.”

In 2009, after I’d posted about what a slam dunk this case would be for Prince, friends of Cariou emailed me with the now-standard traditional photographer’s lament about Prince’s “stealing.” I wrote back to him:

Prince is clearly testing the definition of fair use from the recent Koons case, where two or three transformative gestures–size, format, collaging, overpainting–was considered sufficient. Obviously, Prince publishing a book of the paintings complicates the calculation. And Cariou could argue that some of the works are, indeed, infringing. It’d be a partial victory, but maybe that’d be enough to make the point.

Clearly, that is not what happened.

It’s almost as if Judge Batts, faced with the obvious absurdity of a court weighing, measuring, and calculating the degree of transformation on 29 paintings that included parts of 41 images, opted for the even more obvious absurdity of a court deciding on its own that those paintings have no message and make no commentary, and are thus all infringing works to be outlawed, and even destroyed.

I really want to see Composite Exhibit A now, though.

Alright, I can’t stop at five.

6) Cariou’s supposedly canceled gallery show sounds like bullshit to me.

What’s really amazing about Judge Batts’ decision is how dismissive and diminuitive she is about every assertion Prince and Gagosian’s side makes, and how readily she accepts the most expansive or favorable interpretations of Cariou’s side as settled fact. A clear example of this is the commercial damage Cariou suffered when Prince’s appropriations led directly to the cancellation of an exhibit of Cariou’s Rasta photos. Judge Batts:

Cariou testified that he was negotiating with gallery owner Christianne Celle, who planned to show and sell prints of the Yes, Rasta Photos in her Manhattan Gallery, prior to the Canal Zone show’s opening.

…

Celle originally planned to exhibit between 30 and 40 of the Photos at her gallery, with multiple prints of each to be sold at prices ranging from $3,000 to 20,000, depending on size. She also planned to have Yes, Rasta reprinted for a book signing to be held during the show at her gallery. However, when Celle became aware of the Canal Zone exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, she cancelled the show she and Cariou had discussed. Celle testified that she decided to cancel the show because she did not want to seem to be capitalizing on Prince’s success and notoriety, and because she did not want to exhibit work which had been “done already’ at another gallery.

This is not what the evidence shows at all.

Cariou was deposed on January 12, 2010, and he claimed Celle was his dealer, and had planned a show of Rasta photos for the New York location of her Clic Bookstore & Gallery [p.97]. Celle herself, though, was deposed on Jan. 26, and she said that no, she was not Cariou’s dealer. And their email exchanges from before Prince’s show only mention another body of Cariou’s work, Surfers. Which Celle suggested to her client, the insanely fecund reality TV decorator Robert Novogratz, who was designing a hotel in New Jersey. Celle didn’t take a commission or even discuss prices, sales, prints, anything, with Novogratz, or with Cariou about Novogratz. In both senses of the phrase, it wasn’t any of her business.

A discussion of a Rasta show in New York did seem to take place, but it is not at all clear when. What’s clear is that there was nothing set, and Celle never became Cariou’s dealer. [Though just before she was asked to give a deposition, she did, apparently, accept Cariou’s offer to buy his large collection of rare and vintage photo books for her shop.]

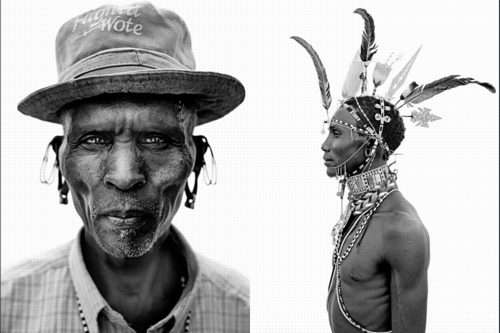

image: Lyle Owerko, the Samburu, via owerko.com]

Celle was at pains to say how Cariou’s Rasta show would have worked in her gallery/shop, especially after she testified that “her goal was to replace probably [probably!] Patrick with” an exhibition of Lyle Owerko’s photos of the Samburu, a deeply “shamanic” Egyptian/Kenyan mountain tribe. But Cariou did. [p. 102]

Q. And why did she think that the Yes Rasta collection fit with her gallery?

MR. BROOKS: Object to the form.

MS. BART [Gagosian’s lawyer]: What’s the basis?

MR. BROOKS: You asked him why did she think.

BY MS. BART:

Q. Did she tell you why she thought this fit with the gallery, did she give you an explanation for that?

A. Well, she does a lot of ethnic photography show.

Q. And she considered the–did she tell you if she considered the Canal Zone show to be an ethnic collection.

MR. BROOKS: Hold on. Canal Zone or Yes Rasta?

Q. I’m sorry, Yes Rasta to be an ethnic collection?

A. Yeah.

First, let’s all have a laugh that Gagosian’s own attorney confused the two bodies of work. If Celle heard of Prince’s show and determined that Cariou was collaborating, and thus got a better offer than her little decorator start-up gallery, then Cariou could have a stronger case for infringement on the grounds of confusion. But that didn’t get cited by Batts at all.

Celle is the former owner/designer of the ubiquitous resortwear chain Calypso. Now I loved Calypso as much as the next Hamptons/St Barths/SoHo-going guy is able to. But it also strikes me that Prince’s work is an entirely credible critique or commentary on the long, checkered history of white, Western civilization’s romantic aestheticization of primitive black folk. And Celle’s ability to swap out one earnest, white photographer’s soulful black & white portraits of a powerful, isolated shamanic tribe with another’s is evidence of the role Cariou’s style of “ethnic” art plays in the dominant culture Prince is commenting on. And his connecting Cariou’s work to similar practices by Picasso are entirely relevant. Prince talked about such things at exhaustive length. And the judge ignored it all.

Also, and it’s an almost insignificant point, dollar-wise, Celle repeatedly points out that she had neither the interest, means, nor the authority to reprint Cariou’s books. Instead, she told Cariou he should get his publisher to reprint several thousand copies of them–so she could sell 50 at a booksigning [p. 156]. Sorry, “50 to 200.”

And one last quote from Celle’s deposition? Does this call her sympathies, and thus, her inclination to tilt her testimony and recollections toward Cariou’s case, into question? Here is an exchange from page 83 of Celle’s deposition, where she is being asked to translate French email exchanges between her and Cariou:

Q. And can you please translate the six lines here?

A. I know really well the “travail” of the work of Mr. Prince and his artistic posture. I have a lawyer, a good lawyer, who si working and very motivated by this lawsuit.

Q. Let me stop you for a second. The phrase “travaille au pourcentage,” what’s that?

A. I have a great lawyer who works–I guess I’m not sure what does that mean because I’m not a lawyer, but probably on a retainer fee. That’s my interpretation, you know, percentage.

Q. “Travaille au pourcentage,” does that mean work on percentage?

A. Yeah, percentage.

Q. Okay. And then keep going. The phrase “et est tres motive”?

A. That is very motivated by the lawsuit or this affair means this business, you know.

Q. The lawyer is very motivated by this affair?

A. Yes.

Q. I see. Go ahead.

I think I see, too. Go ahead.