Photograph of a painting destroyed by Gerhard Richter, Gerhard Richter Archiv via Spiegel

Since I first started looking into them, I’ve wanted to know why Gerhard Richter destroyed some of his paintings. Because, of course, some of them weren’t “destroyed” destroyed, but just painted over, with their previous state being technically defined as a momentary completion, not a work in process. There are only a few like that in the Catalogue Raisonné, though; most of the works listed as “Destroyed” are presumably actually destroyed.

But at least they all got Catalogue Raisonné numbers. Ulrike Knöfel wrote about a different category of destroyed Richters, largely undiscussed and unseen, which were destroyed before the artist began his catalogue raisonné, and which thus, with maybe one exception, don’t have a CR number, and are thus excluded from Richter’s declared oeuvre. Even if they were authentically created by Richter, and shown in exhibitions, and offered for sale.

As Dietmar Elger points out in his biography of Richter, A Life In Painting, Richter actually conceives of the Catalogue Raisonné as a work of art in itself, one which, like Atlas, is still in process.

I recently met with Dr. Elger during a trip to New York, and we spoke about these dynamics of creation, destruction, recognition, and archiving as they play out in Richter’s practice. Elger runs the Gerhard Richter Archiv at the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and maintains the Catalogue Raisonné, so he has a seat at the table for much of this history. After a brief fanboy prelude, in which he signed my book [and my copy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres catalogue raisonne which he was also involved in], we got to talking. [We met for information, not as an actual interview, so I didn’t take notes or record our conversation, and I won’t directly attribute quotes, but just try to capture my recollections.]

“The risk is that I’ll whitewash the other one, too.” “All the more reason to put it away.” “Yes.”

The first thing he wanted to make clear was that Richter destroys paintings all the time. Which is completely understandable as part of the process of making his paintings. If he destroys fewer abstracts, it’s because he knows he can paint over them, so he’s more likely to set a dissatisfying painting aside than to trash it. Anyone who’s seen Corinna Belz’s documentary [above], of course, will recognize this constant questioning of whether a painting is good or done, or whether a painting will stay the way it is.

That was not always the case, though. Richter rather dramatically burned most of his pre-1962 abstract work in the courtyard of the Düsseldorf Academy, and though Elger never pinpointed it, it seems to me that these 60 or so non-CR paintings from 1962-65 were also destroyed together, and not piecemeal. But why?

I’d wondered if perhaps there were condition or material issues with the works; in a 1964 letter, the dealer Heiner Friedrich told the young artist to ditch cheap muslin for the highest quality linen and paint he could find. So maybe these paintings were made with poor materials that didn’t or wouldn’t hold up. Nope, Elger said Richter made that switch almost immediately, though there is apparently an early muslin piece in the archive that’s so thin you can see through it.

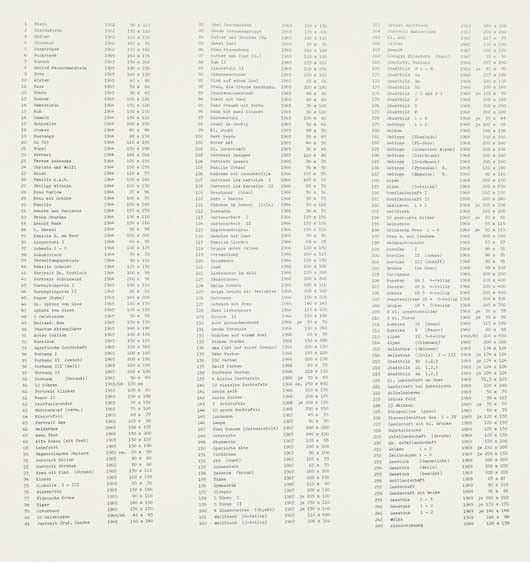

Bilderverzeichnis, 1969, ed. 100, image via liveauctioneers, from a Phillips sale last Jan. for $3,000.

It seems to me that the destruction of these works was part of Richter’s re-evaluation of his work, sometime between 1967 and 1969 and that it’s intertwined with his work on the CR in 1969, when painting was down and Conceptualism was up.

Which, sure, if you think about it: Colour Charts began in 1966; Four Panes of Glass was 1967, and in 1969, Richter published Bilderverzeichnis (Inventory of Pictures) [above], an offset print edition which consists of a numbered list of all the 265 paintings he’d made, and their dates and dimensions. Which looks for all the world like purely conceptual art. And then you realize the last column is full of city scenes and seascapes. Richter had thrown his lot in with painting, while devising a conceptual framework for it.

And so those works which for whatever reason did not fit within that framework got the axe. When the white borders on many early photo paintings like Battleship [below], felt too much like a signature or cliche, they were trashed [and left off the list]. Elger mentioned an early painting of a man on a telephone which actually had a phone cord attached [?!], almost Johns- or Wesselman-style. That was gone. I guess because among Pop artists, Richter only officially liked Lichtenstein.

Photograph of a painting, Battleship(1964), destroyed by Gerhard Richter, Gerhard Richter Archiv via Spiegel

But then you see that some things were added later, or added back. The actual Catalogue Raisonne includes many paintings that were left off Bilderverzeichnis, Richter’s first list, starting with Party, from 1963, which was stuck in at CR2-1, in the middle of 1962. Which should be enough to signal the CR’s constructed, subjective, and not-strictly-chronological nature.

Elger mentioned specifically that several Umgeschalgene Papiere (Turned Paper) paintings had turned up over the years and have been worked back into the CR. Also that there are paintings–or painted things, including gifts and such–which are authentic, but which are not given CR numbers.

With the CR in flux, or in formation, I wondered if Richter actively pursued early works to destroy them, like Johns has been known to do. Apparently he does not; for Richter, leaving them out of the CR is separation enough.

Which should be small comfort for the owners of the early paintings I heard about at the opening of Richteriana. It turns out there are a few very early paintings which were shown, and sold early on, and which have been authenticated, but which are nevertheless not in the CR. They’re the serendipitous survivors of Richter’s late 60s trashings, if not his editing. I’m kind of fascinated to see them.

Previously: Editing A Life In Painting