One of the first and only reports I could find that discussed San Francisco photographer Morton Beebe’s pioneering 1979 copyright infringement lawsuit against Robert Rauschenberg is Gay Morris’s Jan. 1981 article on photo appropriation in ArtNEWS. The title pretty much says it all: “When Artists Use Photographs: Is it fair use, legitimate transformation, or rip-off?” [excerpt here.]

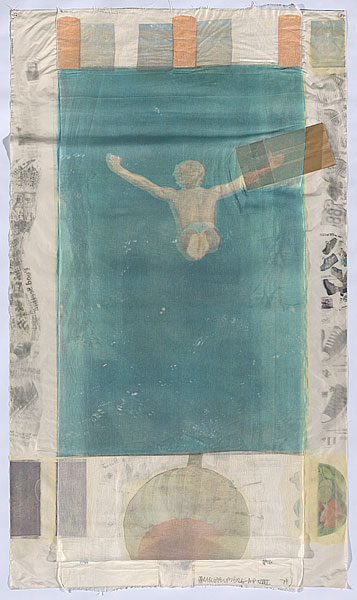

Beebe and Rauschenberg settled before the case really got rolling–for $3,000; a copy of Pull, the Hoarfrost Edition that included a two-layer, screenprinted version of Beebe’s “Diver” image; and a promise of a good faith effort on the part of Gemini and Rauschenberg to include a photo credit for Beebe whenever Pull was exhibited or published. [The extent of Gemini’s subsequent ability and/or effort to secure such credit from institutions can be seen in the print studio’s own catalogue raisonne at the National Gallery of Art. Where there’s no mention of Beebe.]

When I first called him a few weeks ago, Beebe told me what he told Morris, even though the settlement was paltry, and his lawyer got basically all of it [including, if I understand correctly, Beebe’s initial copy of Pull]: I consider it a victory for myself and for photographers.” [update: nope, according to his website Beebe kept his copy of Pull and only sold it in 2004, along with his correspondence, and a print of his original photo.]

Rauschenberg’s and Gemini’s lawyer, Irwin Spiegel, meanwhile, continued to assert the right of artists “working in the medium of collage…to make fair use of prior printed and published materials in the creation” of their original artwork.

Though he opens with Beebe v Rauschenberg, which may be the first actual lawsuit filed against an artist for using a photograph, Morris’s ArtNEWS article covers a lot of photographic territory. It conflates the use of photographs by artists to make paintings or prints–like Warhol’s use of Patricia Caulfield’s flowers photo, taken from a magazine, or Larry Rivers’ drawing based on Arnold Newman’s portrait of Picasso–with companies using photos in fabric patterns and in publications without permission or payment. Which seem like completely different scenarios, though it’s not like the copyright world reflects that, even 30 years later. It’s still “a legal issue,” as Caulfield said in 1981, “because there’s a moral one.”

photo of hibiscus flowers by Modern Photography executive editor Patricia Caulfield, published in that magazine in 1964 where it was found and used by Andy Warhol

What bugged Caulfield, she said, was the way using an image without recognition or permission “denigrate[s] the original talent.” [Definitely read Martha Buskirk’s account of Caufield’s sexist denigration at the hands of Team Warhol in her great 2003 book, The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art.] For Newman, it’s the way these artists “think it’s just a photograph” without considering that there is a person behind the photograph, as Morris writes, “just as there is a person behind a painting.” Beebe’s complaint, too, was primarily one of “recognition.”

And undeserved anonymity never hurt so bad as when you have to find out about it in Robert Hughes’ Time cover story that the World’s Most Famous Artist’s latest , greatest masterpiece was basically your uncredited photo:

But the delicacy of his touch produced its masterpiece in the Hoarfrost series he did with Gemini in 1974. The Hoarfrosts are sheets of silk, chiffon, taffeta, one hung over another. Each sheet is imprinted with images from Rauschenberg’s bank. In Pull, 1974, the dominant one is of a diver vanishing into a pool, seen from above, swallowed in blue immensity like a man on a space walk. No reproduction can attest to the subtlety of its play between the documentary “reality” of collage and the vague beauties of atmosphere.

And that comes just a few paragraphs after Hughes praised Bob’s amazing aversion to fame and his generous love of collaboration, even at his own expense. [“Dozens of people ripped Bob off for money and time,” a friend from the ’60s recalls, “and he knew it, but he never said a word against them.”]

I mention all of this, partly because it still sounds so familiar: the indignation of wronged photographers. The artists defending their innocent intent, freedom of expression and transformative practices. The vast disparities in celebrity, critical response, and economic value between the sourcer and the sourced. The near-universal frustration with the expense and hassle of the court system, which almost always culminates in a privately negotiated, not litigated, settlement.

Beebe told Morris that he settled rather than “risk losing the case on ‘a technicality.'” He told me that Rauschenberg, whose LA-based lawyer had argued to have the case dismissed or moved out of [Beebe’s hometown] San Francisco because of the onerous burden of traveling there, caved rather than go through a deposition. [Which, given Richard Prince’s fraught experience being deposed, is understandable.] Though Beebe also touted the judge’s sympathetic-bordering-on-slamdunk statements to me, I think he recognized that the settlement was the best deal he was gonna get.

I’ve obtained and reviewed the court documents in Beebe v. Rauschenberg. In the case’s one court hearing, held on June 13, 1980, Judge Robert H. Schnacke scoffed at Spiegel’s assertion that just being “an artist of international repute” didn’t mean that Rauschenberg fell under the Bay Area court’s jurisdiction, and anyway, Los Angeles was far easier for his client to reach. And he repeatedly voiced skepticism toward what he called, “copying”:

THE COURT: I’m a little concerned that an artist of international repute finds it necessary to copy photographs into his finished product. I appreciate that I’m not current on all present modes of art, but I thought there was a distinction between copying and artistry.

MR. SPIEGEL: Well, certainly, but that gets into the merits of the case and when we get to the merits–

THE COURT: Apparently the international repute of the artist in some way was relevant to our argument. I was just wondering if [his] international reputation was built upon the fact that he copied other people’s work.

Nevertheless, Judge Schnacke ruled that Beebe would need to front Rauschenberg’s travel expenses to San Francisco for a deposition. Which might have had some impact on Beebe’s priorities as well.

I think I’ll do at least one more post that looks at the way the conflict unfolded–the timeline feels nontrivial to understanding the case itself–and to looking into the “technicalities” of Beebe’s image, where it ran, and how Rauschenberg & Gemini used it. And I’ll probably scan and post at least some of the key court documents, especially Beebe’s complaint and Gemini’s rather extensive information requests and affirmative response.

Meanwhile, to start, I’ve transcribed the first letters of exchange between Beebe and Rauschenberg, which were precipitated, Beebe said, by Christo & Jeanne-Claude recognizing Beebe’s “Diver” from Time Magazine. It all sounded so amenable and promising.

Letter from Morton Beebe to Robert Rauschenberg, dated January 4, 1977, published as Exhibit X in Docket #13, Beebe v Rauschenberg et al, C 79-3372 RHS:

Dear Mr. Rauschenberg:

Imitation is the height of flattery. In seeing the outstanding cover story on you in Time Magazine of November 29, 1976, I noticed, as did a number of my friends, a remarkable similarity between the reproduction of your original piece of art, entitled “PULL, 1974,” of a diver vanishing into a pool. There is a remarkable resemblance to a photograph of mine of a Mexican diver plunging off a cliff in Acapulco, copyrighted in 1972, and published as a portfolio of my work by Nikon, the camera company. It’s remarkable that the image of the boy diving superimposed over the reproduction in Time Magazine match perfectly on a light box. Here enclosed is a copy of the Nikon advertisement of the time.

I have admired your work, in fact while in New York in November I flew down to Washington to see the Museum of Fine Arts’ One Man Show, of your handsome composites, prints and sculptures. You having been in the lead of protecting artists rights, I was stunned to see one of my images so obviously borrowed without recognition. It is much to your credit to have developed a program of buidling royalties into sales contracts for artists.

I would appreciate hearing from you on this matter. When next in New York this spring I hope we shall have a chance to meet. We have friends in common.

Best wishes for a happy new year.

Morton Beebe

Letter to Morton Beebe from Robert Rauschenberg, dated January 27, 1977, published as Exhibit Y in Docket #13, Beebe v Rauschenberg et al, C 79-3372 RHS:

Dear Mr. Beebe,

I was surprised to read your reaction to the imagery I used in “Pull”, 1974. Having used collage in my work since 1949, I have never felt that I was infringing on anyone’s rights as I have consistently transformed these images sympathetically with the use of solvent transfer, collage and reversal as ingredients in the compositions which are dependent on reportage of current events and elements in our current environment hopefully to give the work the possibility of being reconsidered and viewed in a totally new concept. [yes, that’s one nearly unpunctuated sentence. -g.o]

I have received many letters from people expressing their happiness and pride in seeing their images incorporated and transformed in my work. In the past, mutual admiration has led to lasting friendships and, in some cases, have led directly to collaboration, as was the case with Cartier Bresson. I welcome the opportunity to meet you when you are next in New York City. I am traveling a great deal now and, if you would contact Charles Yoder, my curator, he will be able to tell you when a meeting can be arranged.

Wishing you continued success,

Sincerely

Robert Rauschenberg

[2017 update: non-working Beebe’s website have been redirected to a 2011 copy on the Internet Archive.]