I really like Richard Prince’s Hoods; they felt like thoughtful work of their time–I’m thinking of the Loaded Neo-Minimalism of the early 90s, though they bracket that–and they were an unabashedly beautiful standout series at the Guggenheim in 2007. If they’re not under-known, I think they are, Randy Kennedy’s valiant efforts notwithstanding, under-appreciated. [Prince’s comment via Kennedy about not seeing a distinction “between his making and collecting practices” was a huge kick in the pants for me in 2007, btw. More on that another time.]

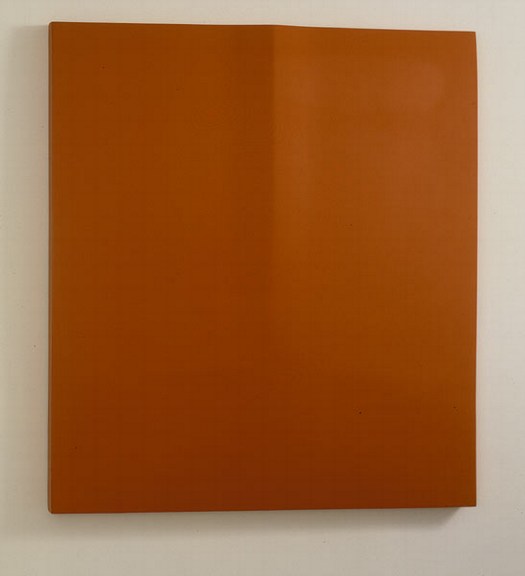

A friend’s sweet Prince Hood at “Spiritual America,” 2007, image: artobserved

Maybe it’s kind of hard to discuss them when the artist pretty much wrapped them up so sweetly himself:

It was the perfect thing to paint. Great size. Great subtext. Great reality. Great thing that actually got painted out there, out there in real life. I mean I didn’t have to make this shit up. It was there. Teenagers knew it. It got ‘teen-aged.’ Primed. Flaked. Stripped. Bondo-ed. Lacquered. Nine coats. Sprayed. Numbered. Advertised on. Raced. Fucking Steve McQueened.

That’s typically cited as coming from 2003, from an interview with Jeffrey Rian published in Phaidon’s Richard Prince monograph, but the Q&A was actually first published in March 1987 in Art in America. [2024 update: Rian emailed to correct this; the Phaidon interview was new and separate from his AiA piece.]

I totally get the car culture finish fetish approach, but I wonder why I like the messier, Bondo-ier ones a little better? Some kind of vestigial taste for the painterly? An unacknowledged prejudice against outsourced fabrication? A closer link to the aesthetic brilliance of the hoods’ found, unfinished driveway project origins?

Untitled (SB Hood #1), 1989, “acrylic, cast fibreglass and wood,” sold for £313,250 last week at Christie’s.

I was pondering on this very question when I saw this hood coming up at Christie’s, where it sold last week. [For my money, I’ve always liked the painting-style, wall-mounted hoods best–the hung-whole ones, not the ones embedded in canvases, which seem superfluous and accede too much for me–but the floor models are Juddful and irreverent, no doubt. Oh, except this one at Larry’s, which, um, Matthew Barney. But the installation does make one think maybe the hoods are only under-appreciated in public discourse. Maybe in their proper context, surrounded by enough architecture and acreage, they’re beloved.]

Anyway, as I’m reading the critical texts at hand–the auction catalogue’s lot notes–I see this:

Inspired by a trip to Los Angeles in 1987, Prince takes the molds of cars he has always admired–Mustangs, Challengers, Chargers, all masculine uber American models– and paints them, celebrating the simultaneous engineering of the American machine and his own sculptural prowess.

And I’m like, wait what? Did Prince take fiberglass molds of car hoods to celebrate his sculptural prowess? I thought the whole point was not having any sculptural prowess, so he ordered them from the back of Hot Rod magazines. Time for a cross-check.

Professor Phillips de Pury, you sold Pro Street (1992-2002), the most expensive Car Hood to date, for $744,000 in 2006; what do you have to say on the matter?

Pro Street is unique amongst Richard Prince’s car hood series; it spans the entire ten years […I- -ed.] he was in production with the other examples from the series. Inspired by a trip to Los Angeles in 1987, Prince takes the molds of cars he has always admired–Mustangs, Challengers, Chargers, all masculine uber American models–and paints them, celebrating the simultaneous engineering of the American machine and his own sculptural prowess.

Yes, well then. That seems appropriate.

Now if we could just clear up a question about the materials. It says Untitled (SB Hood #1) is “acrylic, cast fibreglass and wood.” But when it sold in 1995 it was listed as “Wood & oil, body compound, cast fiberglass.” So I’m just, I know it seems nitpicky, but–you know what, never mind how it’s made or from what, I guess the important thing is it made the reserve.