On Friday March 22, I went to see Kenneth Goldsmith reading Richard Prince’s The Catcher In The Rye in front of a Prince rephotography piece in MoMA’s 2nd Floor galleries. I’d been bummed to have missed Goldsmith’s talk on Wednesday night [granted, I had an opening of my own, but still] so I wanted to make sure I didn’t miss this most appropriate event. When he saw my tweets about it, KG graciously offered to reserve a ticket for me, a gesture which set a certain expectation in my mind of guest lists, seats, or crowd control.

Even as I asked at the desk for the ticket, though, my sense began to change. I suspected, and was right, that this was not a ticketed gig, or even a gallery talk-style crowd with a limited number of slots which, if you didn’t get one, you could shadow and eavesdrop on anyway. The ticket was for getting into the Museum. Which, of all things and all places, I did not need a comp for MoMA.

The Education Department’s online description of the event as a “Guerrilla Reading” still hadn’t registered fully, though, and I wondered where and how it’d start. I asked a couple of guards in the Contemporary Gallery, and then back in the atrium, but they had no idea where Goldsmith’s audience would assemble. They seemed glad for the info, though. I went back to the Prince to wait.

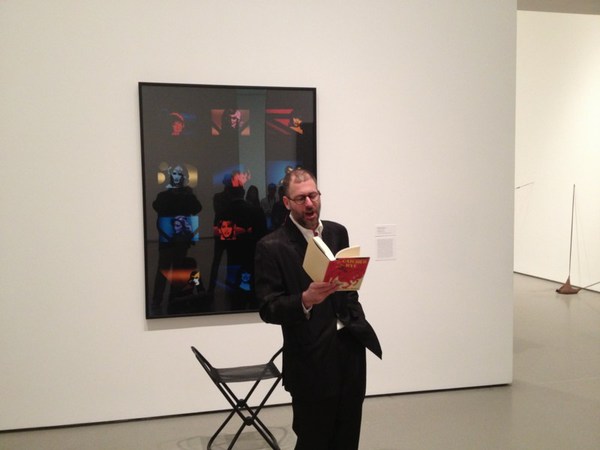

It’s an early 80s grid of 12 photos, or film stills, which I can’t find in the collection. But it had struck me before, and that feeling was even stronger now, as a not particularly iconic Prince. Maybe it had some historical or conceptual significance, but it was no looker. Which made me think about the Modern’s approach to acquiring Prince’s work, which looks pretty uncommitted. There are maybe 20 Princes listed in the collection; most are jokes scrawled on note paper or drawings bundled up in the huge take-it-or-leave-it Rothschild Foundation gift. So yeah, in that context, this C-print is major, but that’s really grading on a curve.

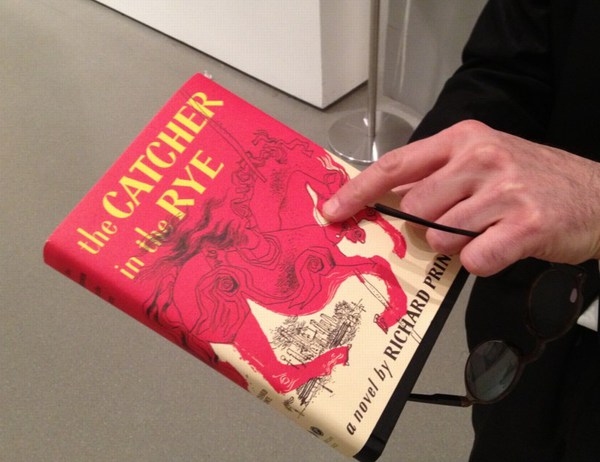

The premise of Goldsmith’s “Poet Laureate” program at the Museum, of inviting writers and poets to select a work on view and then find or create a text to respond to it had clearly, I figured, been flipped for Prince. Goldsmith knew he wanted to read Prince’s Catcher, and was probably glad there was a Prince, any Prince, up to facilitate it. Reviewing it for the Poetry Foundation, Goldsmith called the book Prince’s “strongest and purest work of appropriation in decades.” Coming out in the middle of his copyright infringement lawsuit over the Canal Zone paintings, which was decided disastrously [from RP’s perspective] by the same judge who sided with Salinger to ban publication of an unauthorized Catcher in the Rye sequel, I’d tend to agree.

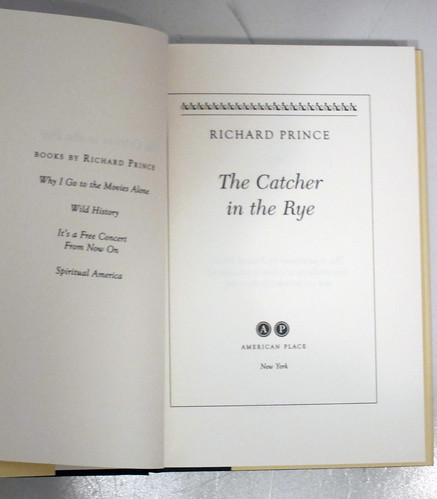

RP TCITR frontispiece image via 6 decades books’ flickr

[One interesting thing that maybe doesn’t pertain here is Prince’s colophon, which reads, “This is an artwork by Richard Prince. Any similarity to a book is coincidental and not intended by the artist. © Richard Prince.”

Or maybe it does pertain. It’s one of the few clues to the work’s identity and existence. Miss it, and your entire context for the object in your hand, or the text on the page, or the voice in the gallery, changes completely.

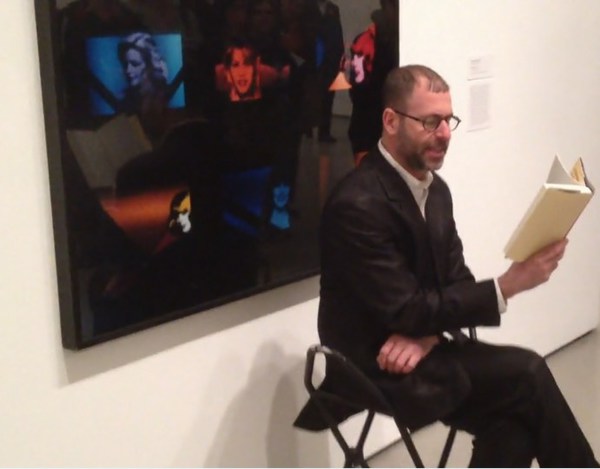

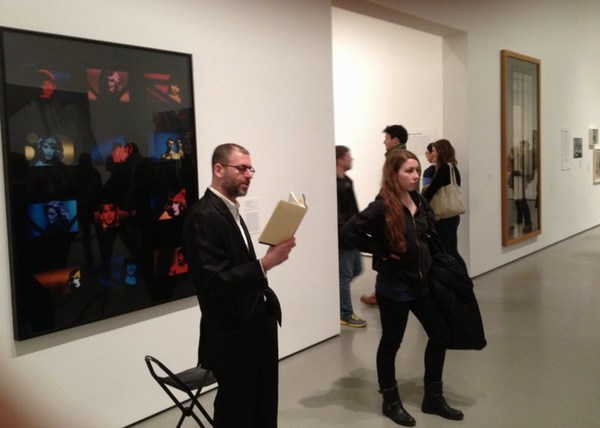

And that is what, I think, happened quite a bit during Goldsmith’s MoMA reading. When he finally did arrive at Prince’s photograph, he was accompanied by a couple of folks from the Museum’s Education Department, but there was no intro, no obviousness. We four were the audience. KG said hi, plopped his bag in the corner, sat on a little museum folding stool, and began reading. And if you didn’t catch the “by Richard Prince” at the beginning [try it yourself, it’s at 00:01 in this audio excerpt], or get in close to read Prince’s name under Goldsmith’s hand on the cover, you thought you were hearing someone reading from the 1st edition of Salinger’s novel. Which would be a pretty inexplicable thing to stumble across in the middle of the Museum of freaking Modern Art.

The happenstance encounter with a guy intensely reading a familiar-sounding tale for some reason, that was the experience. Even as I expected it, it’s remarkable how quickly the White Cube subsumed Goldsmith’s performance. People would stay to watch and listen for a few minutes, then leave. When a couple of people sat on the floor, a few others followed with no problem from the guard. When, after a rotation [of both guard and audience], someone tried to sit down, though, museum protocol reasserted itself, and they would get stood up.

Sometimes there’d be only one or two people. A senior member of the Museum’s curatorial staff stopped by; he laughed as we listened, at how quickly the Catcher in the Rye text came back to him. I told him I thought Prince really managed to capture the flavor of the original. For a couple of minutes, it was just me watching, though there was always someone moving in or through the gallery.

Suddenly Tilda Swinton appeared, walking briskly and straight toward me. She was wearing an emerald green sleeveless dress. [At this point, I should give equal time to Goldsmith’s outfit, which was, for him, shockingly sober: he later told me during a break that his dark suit and white shirt was his nod to Prince’s own preferred, subdued public look.]. A Museum staffer hustling alongside Swinton motioned to a guard, who unroped the doorway next to me, and the two disappeared into an under-installation gallery. [I assumed at the time that Swinton was attending some kind of New Directors/New Films event, but it was only a day later that she appeared, in jeans, in a glass box, making the first of an even more guerrilla gallery performance than Goldsmith’s. So maybe it was something about that.]

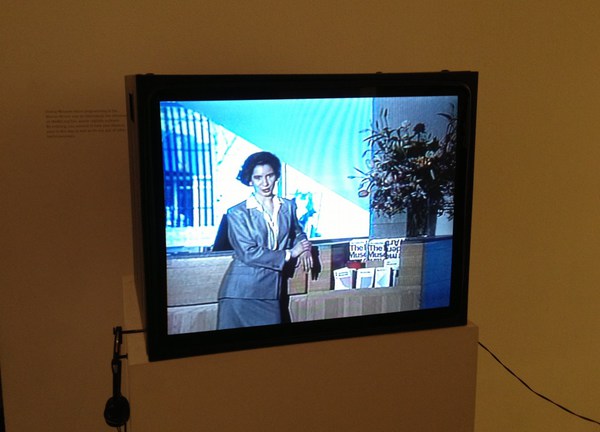

A couple of times Goldsmith pulled a flask out of his pocket and asked me if I’d go refill it. It was the only way to get the water into the gallery, he joked, and he was dying of thirst. It was on my way to the fountain for the first time that I passed a video of Andrea Fraser’s 1989 piece, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, and it hit me that here was a crucial context for Goldsmith’s project and relationship with the Museum.

Fraser had originally created A Gallery Talk and her docent character/construct Jane Castleton at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but MoMA’s version was adapted to itself and the Metropolitan. Personally, I find it a more universal and a more powerful critique of the structural inequality our philanthropic system is designed to perpetuate, and it feels like it could have been shot today–or in 2011, at an Occupy Museums rally. It really is devastating. [For a mute art video on a monitor in a corner.]

Almost 25 years ago in A Gallery Talk, Fraser had nailed the questions Goldsmith’s reading was raising right then for me: what happens in a museum, what belongs in a museum, what gets left out, who decides, what interests are served, what do we experience or expect from art–really, what’s the point of art and creativity at all. And both Goldsmith and Fraser had zeroed in on the Education Department, the institution’s designated mediator between itself, the art, and the public.

I’d like to say that being willing to accomodate the uncertainties of live people and events in the galleries, whether Goldsmith’s “Poet Laureate” set or the larger “Artists Experiment” program, are a mark of progress for MoMA’s Education Department. But it’s more accurately a mark of how thoroughly the institutions of art are able to subsume the critiques of Institutional Critique, and to package this self-examination as part of its programmatic offering.

As it turns out, in the lecture I’d missed, Goldsmith talked about this very issue, critiquing the institution from the inside. The Department of Education & Public Programs, he said, was the secret back door to the Museum, where artists and subversive poets could enter unannounced. And then proceed, presumably, to commence their cultural upheavals. [I think this is the permanent streaming archive of the talk.]

Goldsmith, who founded the incomparable Ubu, is fond of saying that archiving is the new folk art. His talk at MoMA in March makes a similar case for avant-garde poetry, Relational Aesthetics, and Institutional Critique. Which, given what we’ve come to learn about the institution’s view of folk art, cannot be very reassuring.

Anyway, after an hour and a bit, I was needing to leave, but Goldsmith was still going strong. His Museum staff audience had all gone; the mass of Free Friday Nights visitors were starting to line up on 53rd St. In a 2-hour reading, Goldsmith figured, he would probably get about halfway through Prince’s text. I left him there with his public, who would occasionally linger, try to make out what was going on, maybe think they had, and move on. Or as they did with Starry Night and Munch’s Scream, they’d just pose next to him for a picture.

Uncontested Spaces: A Guerrilla Reading By Kenneth Goldsmith [moma]

Kenneth Goldsmith reading Richard Prince’s The Catcher In The Rye at MoMA, March 22, 2013 [vimeo]

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk [moma.org]