Hang with me, there’s a lot here, and I don’t really have the bandwidth to go into it right now, so I’m just going to slap it up here for now:

Walker Art Center curator Bart Ryan recently talked with Liam Gillick and Hito Steyerl about writing as part of their/art practice.

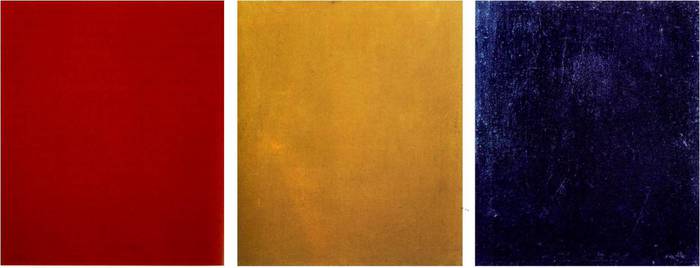

It’s part of 9 Artists, Ryan’s show about, well, I’m sure the title says plenty. Until I read the 28,000-word catalogue essay, I’m just going with the title. Steyerl’s 2007 work Red Alert is in the show, though. It’s three redscreen monochrome monitors mounted in landscape, a gesture she describes as “the logical end of the documentary genre,”

Pure Red Color (Chistyi krasnyi tsvet), Pure Yellow Color (Chistyi

zheltyi tsvet), Pure Blue Color (Chistyi sinii tsvet), 1921, each panel 24.5 x 21 or so

in a similar way to Rodchenko declaring his 1921 three-panel monochrome, Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure Blue Color represented the logical end of painting.

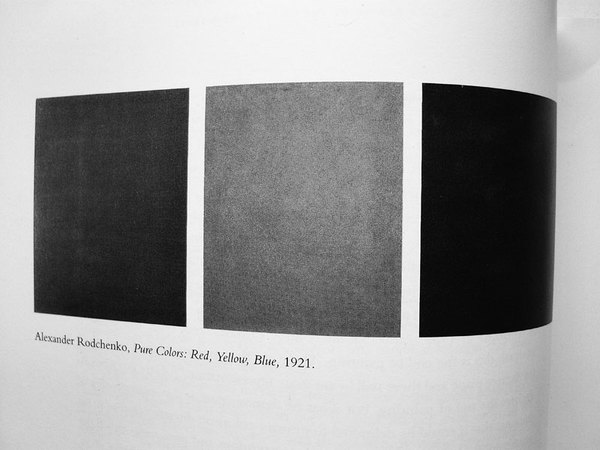

image of October reproduction of Rodchenko monochromes via e-flux

Which paintings now always remind me of a 2010 e-flux journal article about October magazine, which it turns out I’d misremembered a bit, but that’s OK. Bernard Ortiz Campo wondered about art writing and why October only printed black & white images of artworks:

In the spring of 2000 in an article on Nikolai Tarabukin, the journal reproduced three monochrome paintings by Alexander Rodchenko: Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, and Pure Blue Color. These three paintings, reproduced in black and white, resulted in three rectangles showing different shades of gray. As I looked at them, I found myself asking whether it made sense to reproduce them at all. I even entertained the possibility that the reproductions weren’t images of the actual paintings, that perhaps they had been “rendered” by the journal’s photomechanical process, and that the only thing that identified them as paintings by Rodchenko were the captions. I intuited that this extreme case could offer a reason for the black-and-white reproductions–hypothetical, of course, for being the fruit of my speculation, but a reason nonetheless.

I remembered this as imagining that the Rodchenko monochromes themselves didn’t actually exist except as illustrations. And black & white ones at that.

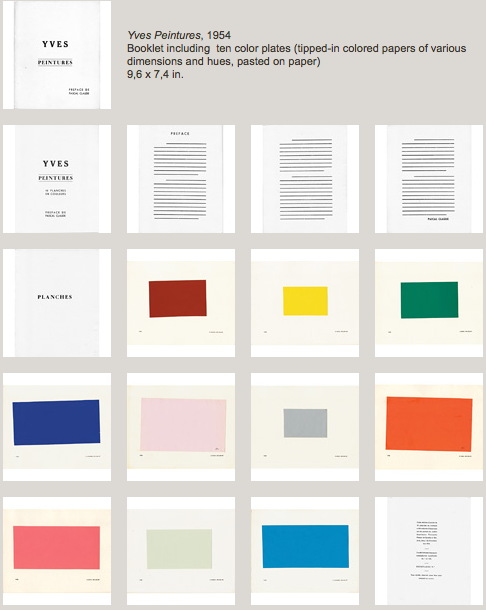

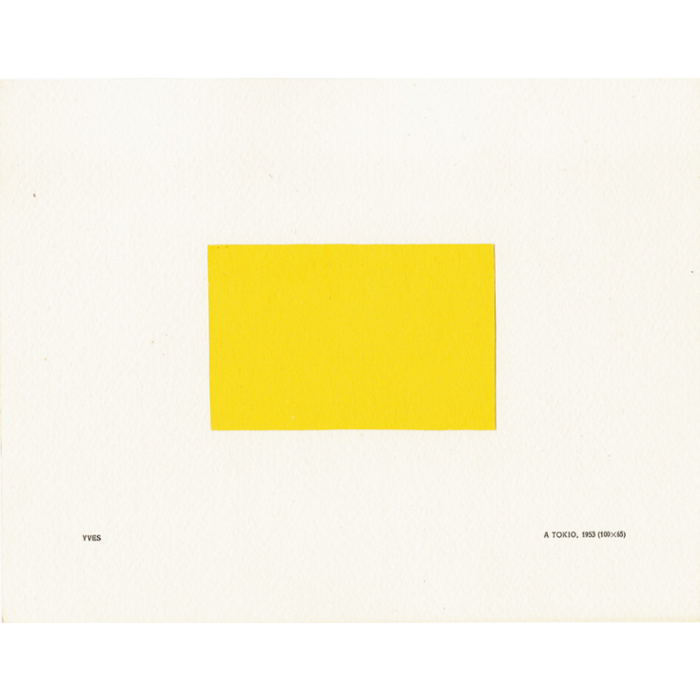

Yves Peintures, 1954, image: yveskleinarchives.org

Which reminded me of one of my absolute favorite Yves Klein works, a book, or maybe it’s a portfolio? More a catalogue. Yves Peintures bears the mind-bogglingly early date of 1954. The Klein Archives lists it as “his first public artistic action.” It is a looseleaf booklet with ten color plates of monochrome paintings that don’t exist.

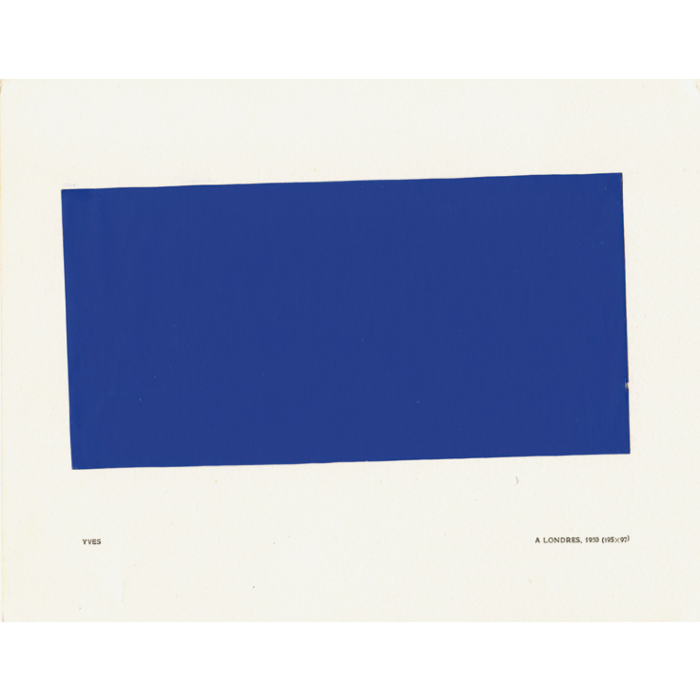

They are commercial samples of colored paper, tipped in and given arbitrary dimensions and locales/titles: a Londres, 1950 (195 x 97); a Tokio, 1953 (100 x 65), &c. The accompanying text, credited to Pascal Claude, is entirely strikethroughs, assuming it was ever any less fictional than the paintings. [Speaking of writing, Philippe Vergne loves Yves Peintures even more than I do; he goes nuts for it in this 2010 essay about how Klein basically started and ended everything ever.]

I’ve never been able to figure out quite how many copies of Yves Peintures exist, much less how I will get my hands on one. The Archives illustrates five examples, each different. [Actually the colophon says it was published in a numbered edition of 150, but less than 10 are thought to have survived.]

The Archives has also authorized a facsimile of Yves Peintures, produced by Editions Delicta, in an edition of 400. I don’t know how many variations are in that one, if any. I will guess none. The obvious solution is to make one myself, as the logical end of fictional monochrome artist book making.