Holy smokes, who knew that Rhonda Lieberman had the complete works of Thorstein Veblen in that Celine bag, and that she’s not afraid to swing it?

After years of quiet one-eyebrow-raised reportage from the art world circuit, Lieberman has published a blistering takedown of neo-Gilded-Age collecting in, of course, The Baffler. And yet somehow, she seems to manage to leave most [non-Crystal] bridges unburned. No small feat.

I was ready to storm the ramparts, when I was caught by this paragraph:

Bernie Madoff’s prized piece of office art was a four-foot sculpture of a screw that he frequently dusted off himself (he, like Donald Trump and scores of other plutocrats, is a notorious neat freak). A defense lawyer pleaded for the valued object to be photoshopped out of court documents, lest it be prejudicial to members of the jury. When Madoff’s Ponzi scheme went bust, J. Ezra Merkin, whose feeder funds supplied Madoff with investors, was no longer Mastering the Universe quite so comfortably. So he sold his stunning batch of Rothkos for $310 million. Whenever I see a Rothko I think of Madoff, and how the afterlife of modern art is now yoked to the pissing matches performed by the big swinging dicks of Wall Street.

Merkin’s Rothko firesale in the earliest days of the Madoff scandal, I know. But this screw is new to me. Let’s learn more.

OK, that was fast, here it is:

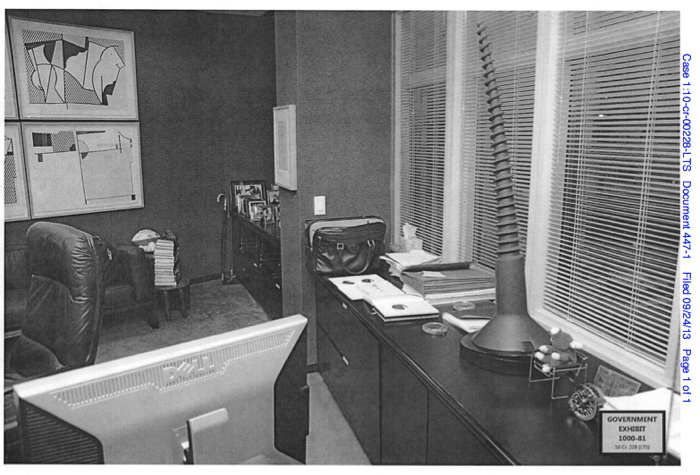

Government Exhibit 1000-81, document 447-1, 2008 photo of Bernard Madoff’s office showing [r to l] a Beanie Baby in a tiny Wassily chair; Claes Oldenburg’sSoft Screw, 1976; Henri Matisse’s Tete de Femme, 1952; and plates III & VI of Roy Lichtenstein’s Bull Profile Series, 1973

The court case is for a group of former Madoff employees, and last September federal prosecutors and defense attorneys debated the meaning of the sculpture, its symbolic embodiment of the firm’s “lad culture,” and its implications for the alleged accomplices’ case:

The screw sculpture appeared in photos of Madoff’s desk, and a witness would testify that it was removed during an SEC on-site examination in 2005, prosecutors said. But defense lawyers argued that it was unfair to link a possible symbol of ripping off investors to their clients.

“The issue with this screw is that there is a secondary meaning that the government is going to try to implant with the jury, that it was a kind of inside joke… that was known to some of the defendants here,” said Eric Breslin, the lawyer to Madoff account manager Joann Crupi.

That quote is from Newsday, quoted in a lengthier discussion at Above the Law about the implications of the judge’s unusual order that evidence be Photoshopped before being introduced. I’m still trying to find the redacted image.

Anyway, the sculpture, as you might guess, is by Claes Oldenburg. It’s called Soft Screw, from a 1976 Gemini G.E.L. edition in cast black urethane on a mahogany base. Madoff’s example is signed 15/24. There were also three artist proofs, one special proof, and three publisher’s proofs.

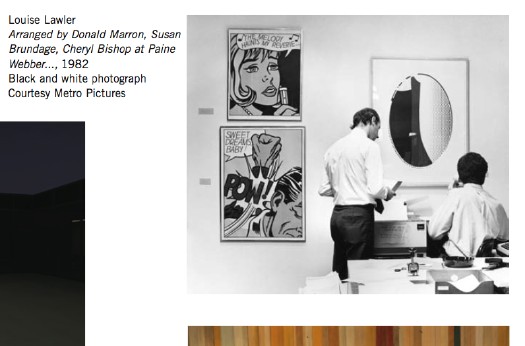

In documenting the “crime scene,” government investigators have inadvertently made their own Louise Lawler photo. The Lichtensteins remind me of an actual Lawler, Arranged by Donald Marron, Susand Brundage, Cheryl Bishop at Paine Webber, 1982 [above], which was in the Met’s Pictures Generation exhibition in 2009. The self-satisfied wall text accompanying that Lawler bugged me because of how it privileged museums as interpreters of meaning.

Lawler’s work is so fascinating precisely because it explores the life [sic] of art outside of the white-glove, white cube of the museum, and it gains power from the unexpected resonance between the autumnal colors of a Pollock and the Limoges; between a Lichtenstein print and a fax machine. It should be a reminder of what gets lost when art’s only presumed destiny is to end up in a museum.

And really, is there a greater reminder of loss than Bernie Madoff? Let’s consider the meaning of a giant, soft screw in the office of a legendary investment manager who everyone he worked with quietly knew was a running a decades-long con. Or the undiluted symbolism of Lichtenstein & Picasso bulls in the collection of the former chairman of NASDAQ. Or Jasper Johns numbers prints 0-9 and Twombly’s graffito abstractions in a firm with an entire floor dedicated to forging a paper trail for its non-existent transactions.

Madoff’s edition of Lichtenstein’s Bull Profile Series, 1973, is #31/100, btw. image: USG Exhibit 1000-79

Maybe it’s here in the offices and conference rooms of the financial industry where art functions best: as abstractions of the predatory system it’s embedded in; as markers of cultural refinement in a ruthless boiler room of capitalism; as a spoonful of aesthetic sugar to help the banking go down.

And nothing says art commodification quite like the large-edition prints Madoff favored. Most of the three dozen or so name brand artworks decorating Madoff’s office were made in editions of 75, 100, 150, even 250 and 300. And soon you’ll be able to invest yourself, because it will all be for sale. The Wall Street Journal reported last summer that a bankruptcy judge approved the sale of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Services (BLMIS)’s art and furniture at Sotheby’s. Though originally planned for last fall, I just spoke with Sotheby’s, and the Madoff hoard, such as it is, will be included in the prints sale this May.

another example exhibited

Which gets me wondering: would it be possible to capture and preserve the Madoffian implications of these works as they are wrung through the art market? Can we flag these specific examples of these prints as Collection Bernard Madoff forever, and see how they perform going forward? Not just in terms of the market, but in their critical dialogue, their meaning? Can Madoff’s example, 4/24, of Ellsworth Kelly’s Colored Paper Image XIV (Yellow Curve), 1976, mean something different than ed. 22/24, above, which Susan Sheehan Gallery just brought to the Armory show? And can ed. 15/24 be forever known as Bernard Madoff’s Soft Screw?

Bunch of Asparagus, 1880, Edouard Manet, collection Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne, image: cabbagegames

In his Project 74, Hans Haacke pieced together the ownership history of a little Manet painting, Bunch of Asparagus, from the German-Jewish artist whose work had been banned by the Nazis, to the ex-Nazi banker who headed the committee which bought the work for the the Wallraf-Richartz Museum. Can we not do the same thing prospectively, writing Madoff into the history of each of his artworks as they go back into circulation? I think we can.

UPDATE Wow, these screws are so screwed. Art conservation researcher Joy Bloser emails that around 2007, various examples of Oldenburg’s Soft Screw started melting. Or to put it another way, THEY STARTED MELTING. The urethane began an irreversible process of depolymerization, reverting to a liquid. The bendy tip of the screw usually starts dripping away. Here’s one image of a drippy screw; here’s an album of several more screws from the edition. What an incredible mess. Apparently, urethane reversion is exacerbated by inconsistent mixing; or exposure to light, heat, or moisture. When screws became discolored, some gallerists apparently recommended collectors just polish them up with Armor-All. Bernard Madoff insisting on dusting his own Soft Screw may be one of the most prudent, conservation-minded decisions he ever made.

Hoard d’Oeuvres [thebaffler via Giovanni Garcia-Fenech]

Bernie Madoff’s Giant Screw: Is Photoshop A Proper Rule 403 Remedy? [abovethelaw]

Madoff Office Furniture, Art to be Sold at Auction [wsj]

Exhibit A: Property from BLMIS, the 8-page list of Bernard Madoff’s artworks [PDF, published by WSJ at documentcloud.org, backup copy here at greg.org]