Whether it heals all wounds, time does cool all hot takes. When the Gursky show opened at the Hayward Gallery in January, I was immediately set off by this kicker from Laura Cumming’s review in The Guardian:

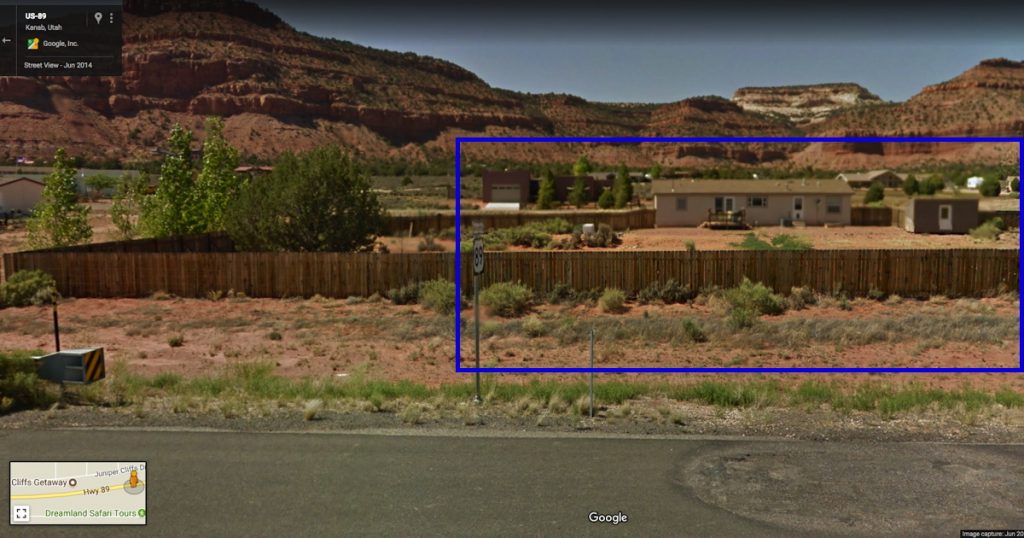

But the show’s masterpiece is unlike almost anything Gursky has made before. It is a new work, a single shot of some prefab houses skimmed on a mobile phone while driving through Utah. The photograph registers the speed of the car racing through the landscape – and modern life – in all its random glitches and blurs. At the same time, the houses look perilously ephemeral against the ancient mountains behind them. This fragile little thing, a spontaneous and disposable shot, is enlarged to the size of a cinema screen – a monumental homage to the mobile phone and the outsize role it plays in depicting our times.

Not just Gursky using a phonecam, but Gursky doing something new? Now that is news.

In addition to the phone and all its quotidian implications, what caught my attention was the subject: Utah. I had, just a couple of weeks before, driven along the very road in southern Utah as Gursky. I was also in the middle of a two-month mess on my server, which necessitated rebuilding my blog and its underlying software and databases. But that could wait until I identified the precise stretch of highway Gursky had captured. So I set out again, on Google Street View.

From the geology and the development, it was possible to narrow down the site of Gursky’s photos to the roads around Zion National Park, and east from Zion and Kanab, toward Grand Escalante and Staircase National Monuments. The sections of this rural, two-lane highway with guard rails and fresh blacktop were even fewer. And none of it matched.

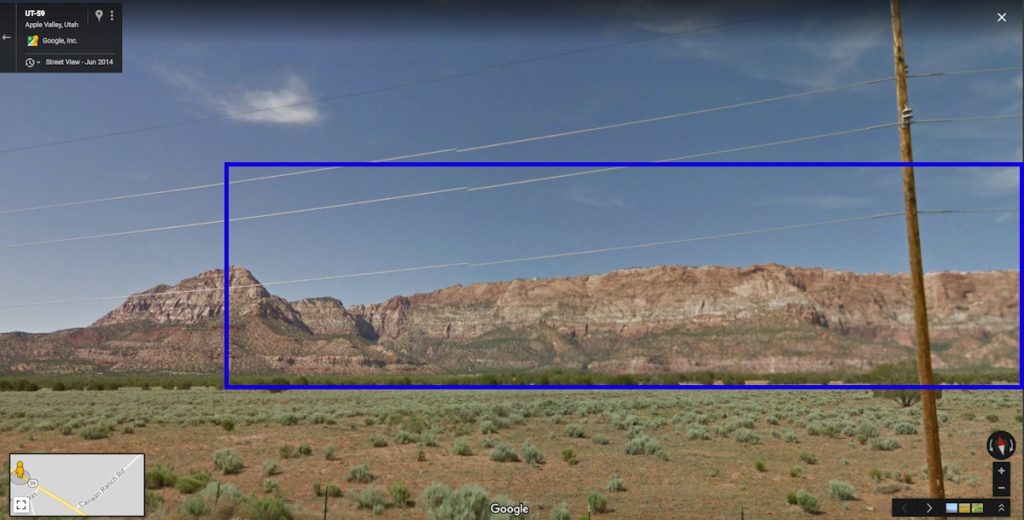

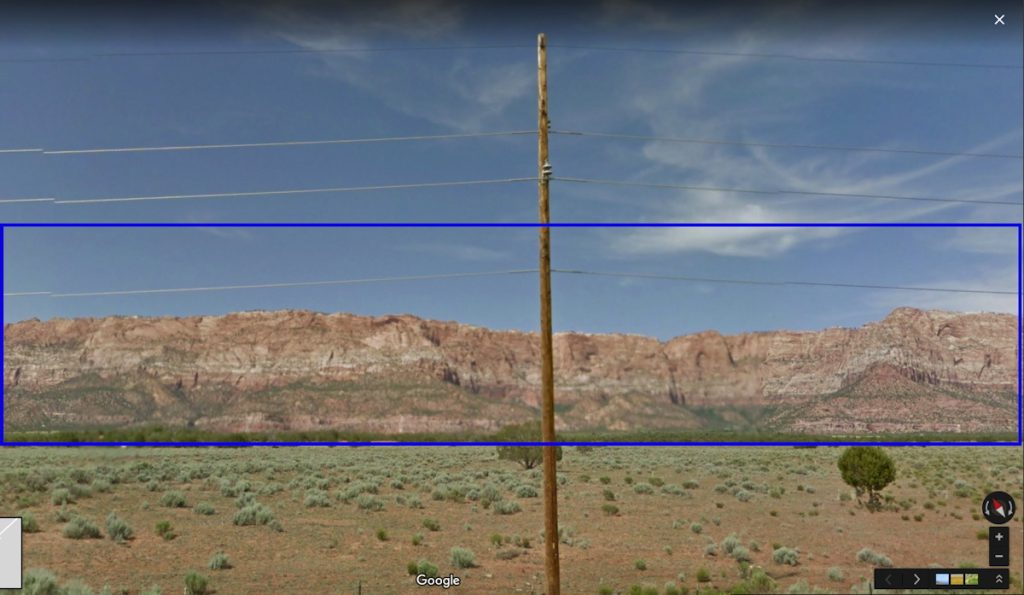

This section of Utah is very sparsely populated, and very few roads cross it at all. So the options dwindled very quickly. But on the road between St George and the border-straddling polygamist towns of Hildale, UT and Colorado City, AZ, I recognized the striated mountain range immediately. But there were no houses at all.

Which, two things: it’s now obviously a composite. But before that, those poles. Gursky’s original image is full of blurs and artifacts, including what are apparently some disembodied pole fragments. These artifacts, coupled with the disparate blur on houses, patios, guard rail, etc., led me to assume Gursky had experimented with an iPhone’s panorama feature from a moving car. That he was exploiting the stitching algorithm of the phone, a source of found digital manipulation.

But of course, this turned out not to be the case. What hit me during these first few days was that this Gursky was being presented as a single image when it was now obviously a composite.

And so I set out to find the site of the other, lower half. Which, with every Streetviewed mile, was turning out to be an entirely fictional, constructed composition. While trying to rebuild my webserver I wandered the highways again, finding this or that house; meanwhile the more accurate version of Gursky’s process emerged: that he’d taken photos with a phone, and then returned to reshoot sites with his regular camera, and–like always–he just fixed the whole thing in post.

So my Gursky bust turned into a Guardian factcheck. And I was left dissatisfied, again, by Gursky’s view, even as I grew intrigued by Google’s. I found myself indexing the differences: vantage point, height, date, blur, glitch, and stitching. I imagined Streetview’s rooftop, panoramic compositor, and Gursky’s passenger driveby–which turned out to be a tripod on the shoulder. And I tried to imagine what it’s like for a maker of ambitiously scaled images to work in a world where giant companies are constantly taking a picture of the entire earth. Maybe the better digital analog for Gursky’s practice isn’t Google at all, but etsy.

In good etsy form, I have knocked off Gursky’s image by collaging the elements I’ve found. If/as I find more, I’ll add them until…until what? I don’t know, I guess until it’s done, or I get bored. If you see something say something.