I just learned that Joseph M. Carrier, the former RAND Corporation analyst in Vietnam, who cruised Danh Vo in 2006 at an artist talk for a residency in Pacific Palisades, then invited him to his house, showed him his vast archive of photos, documentation, research, ethnographic material, and erotica, then invited him to go to Vietnam together, has been alive all this time, and only passed away at the end of November 2020.

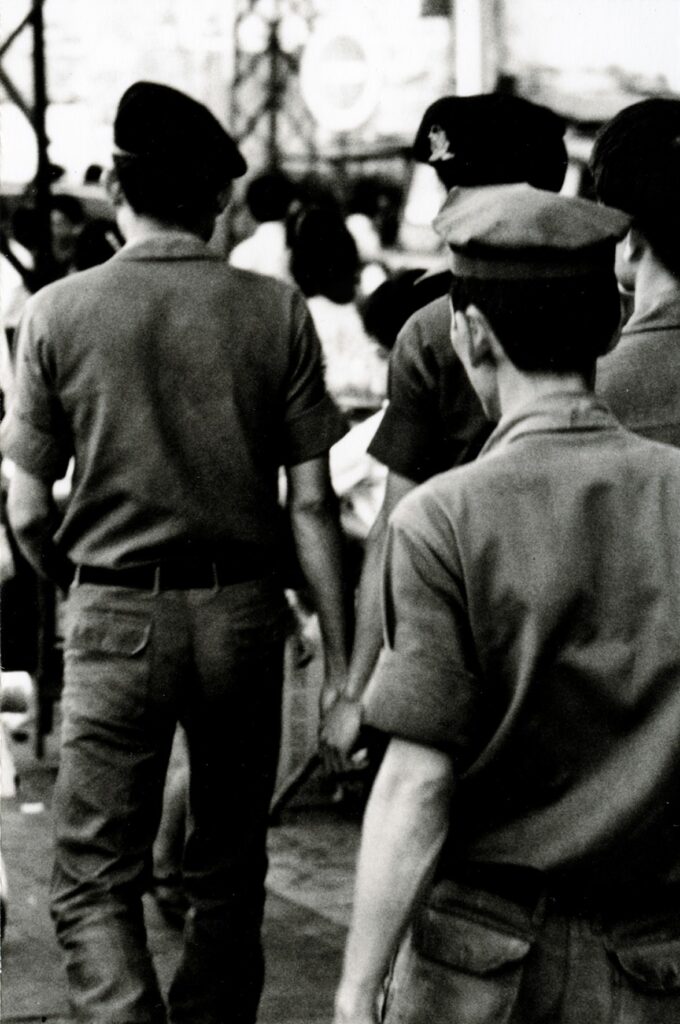

Carrier has been an important presence in Vo’s work and career. Vo first showed creepshots Carrier took of young men on the streets of Vietnam as Good Life (1966/2007) at Bortolozzi in Berlin, but these homosocial images have been included in many of Vo’s shows since. He’s discussed them both in terms of Carrier’s own experience as a gay man fired for his gayness, and as projected autobiographical content of Vo’s own lost life in the war-wracked country he fled as a child in the 1970s.

As Vo explained to Adam Carr in 2007 before the Berlin show opened:

What is incredible is that he kept diaries, papers from the RAND Corporation, love letters and lots of photos and original negatives. What’s more incredible is that he gave it all to me!

Primarily I think this whole affair I have with Joe’s material is an act of divine justice for not really having my own history. As a refugee my parents left it all behind, mentally and also physically. No pictures or documents of my family’s life in Vietnam exist, and its a kind of magical coincidence that I got this archive which I strangely but sincerely feel belongs to me.

Sure enough, at an Art Basel Statements installation in 2008, Vo exhibited a copy of Carrier’s will, which mentioned Vo’s inheriting Carrier’s archive.

The three-way affair between Vo, Joe, and his material also manifested in a 2009 show at Buchholz in Cologne, “Boys seen through a shop window.” Carrier wrote the press release for the show [pdf] in strikingly personal first-person non-artspeak, but the show really did look like Vo had cleaned out Carrier’s house and turned it into one giant installation piece.

But Carrier was still alive and going strong in 2010, when Vo talked of staying with him on another trip to LA, before his Artists Space show which featured photogravures made of Carrier’s images.

At the time the perceived dynamic of Vo’s relationship with Carrier was colored by Vo’s relationship with Michael Elmgreen, who he was dating at the time, but whose signature he also secretly forged on a Danish Arts Council grant so he could go to the opening of Prada Marfa as a photographer’s assistant.

Vo talked a bit about the ambivalence and instrumentalization of relationships and relationship structures in 2007 [when he was still marrying friends and immediately divorcing them, just to add to his official last name], in the context of a refugee’s desperate survival tactics. But, as he said even then, “I was a boat refugee when I was four, but I’m pretty dry now.”

Vo’s work, and his collaborations, especially early on, were unsettling, not just because of what he called “parasitism,” but because of his forthright ambivalence even then to forefront his questioning of the fundamental assumptions of human interaction. Finding out about Carrier’s death–and the fascinating, complicated and varied life he led–underscores the efficiency of the art context to reduce him to a sort of found object. But it also exposes the limitations we all face in understanding the nuances of someone else’s relationships. Which feels like part of Vo’s point all along. Meanwhile, I think Danh’s gonna need a bigger storage unit.

Obituary: Joseph M. Carrier [palipost.com]