This artnet investigation by Zachary Small into attempts by his dealers to uncancel Chuck Close ends up highlighting the failures of the art world to deal with sexual harassment, especially when there’s money to be made. Or male power to be preserved. Small notes how Close’s gallerists at Pace protected him, thwarted attempts by those accusing him of coercion to seek accountability, and sought to reboot his presence and market–and who themselves turned out to be perpetrators of workplace abuse, for which they’ve suffered no professional consequences.

Rob Storr also turns out to be spineless when the artist whose MoMA retrospective he curated sexually harassed a student at the art school he’d invited him to, Yale.

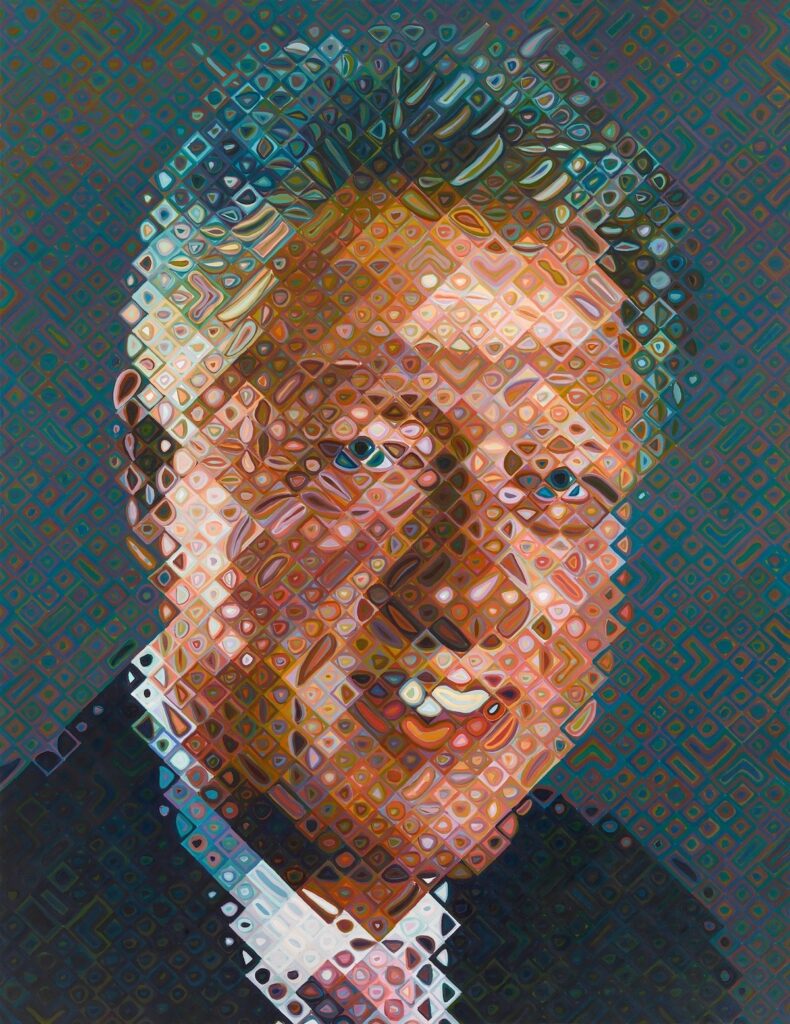

Small’s article reminds me that though Close’s work is now not on view in many museums, his 2006 portrait of another sexual predator whose legacy remains unresolved, Bill Clinton, continues to hang at the National Portrait Gallery, with a two-sentence acknowledgement of Close’s accusers. [The new portrait of Donald Trump nearby contains no such disclaimer.]

But then, this is an art world where Carl Andre could keep showing with his dealer Paula Cooper, and could eventually get a five-museum international retrospective, after killing his wife. So it’s not like Arne Glimcher’s got no reason to hope.

Maybe the solution is for museums to lean into it, and present Close’s work as what it turns out to be: the product of a sexual harrasser in a system set up to coddle them. How does Close’s intense, close-up portraiture of his friends and the powerful reflect the male-dominated structures and networks that made his fortune? Museums should be free from worrying about what impact actual, critical curating might have on the market value of their Closes, right? Though it might be tough to get lenders.