For too many years this blog was the top search result for Ellsworth Kelly postcards. I’d Google it myself, hoping to find more, and wondering if my compilations of collaged postcards Kelly made over the years would ever lure some to me. It has not, but last fall, I was rewarded with news from the Tang Museum at Skidmore College of the first comprehensive exhibition of Kelly’s postcards, organized by the Tang’s Ian Berry in conjunction with the artist’s studio and Jessica Eisenthal. Schedule complications kept me from attending, but there is an excellent-looking catalogue being released this spring, and the show will open late this summer at the Blanton Museum at UT Austin.

Though a couple we included in his Guggenheim retrospective in 1996, most of Kelly’s 400 or so postcards made between 1949 and 2005 have never been shown or published. Each venue will show a distinct selection of 150 of the works, and the catalogue reproduces 216 postcards at full scale. It is a veritable facsimile object blockbuster–but I still want to see the real things in person.

The vast majority of the postcards here are from the collection of Kelly, who died in 2015, and his partner Jack Shear, who oversees the artist’s Studio, Archive, and Foundation. That makes them feel personal, like sketches or collages the artist made for himself.

But Kelly also sent them to friends. Tricia Y. Paik of Mount Holyoke College spent many years researching Kelly’s postcard practice and talking with him about it. He saw them in the spirit of Mail Art, and he cared about them enough that he learned to send them “to friends who would keep them, who wouldn’t junk them.”

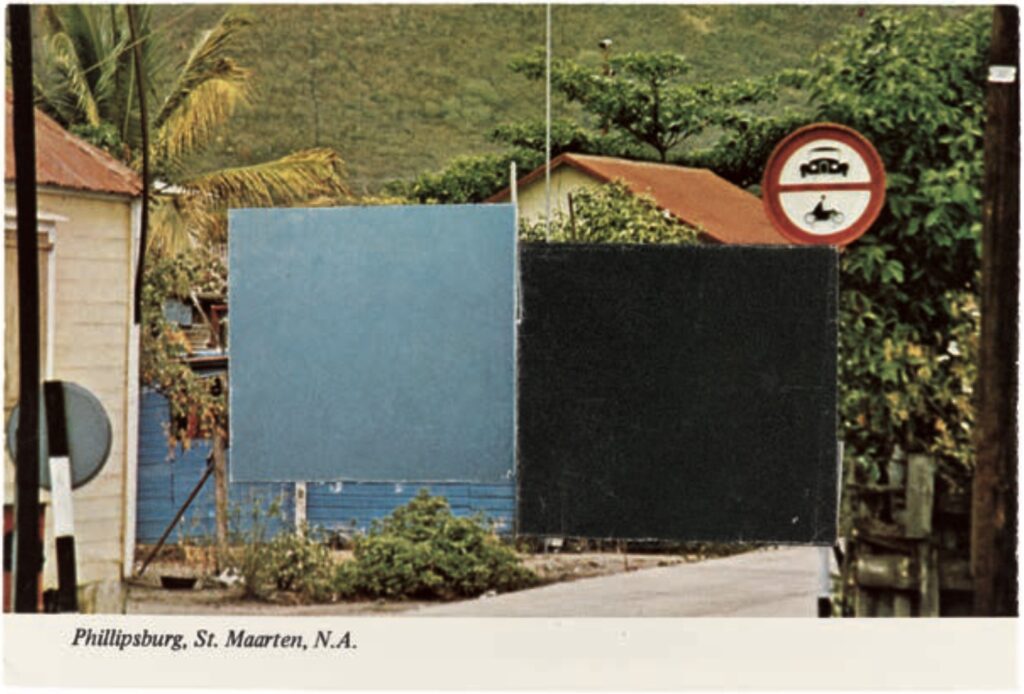

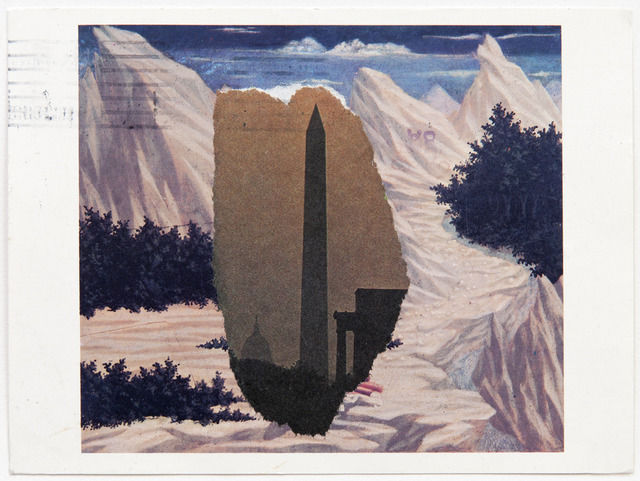

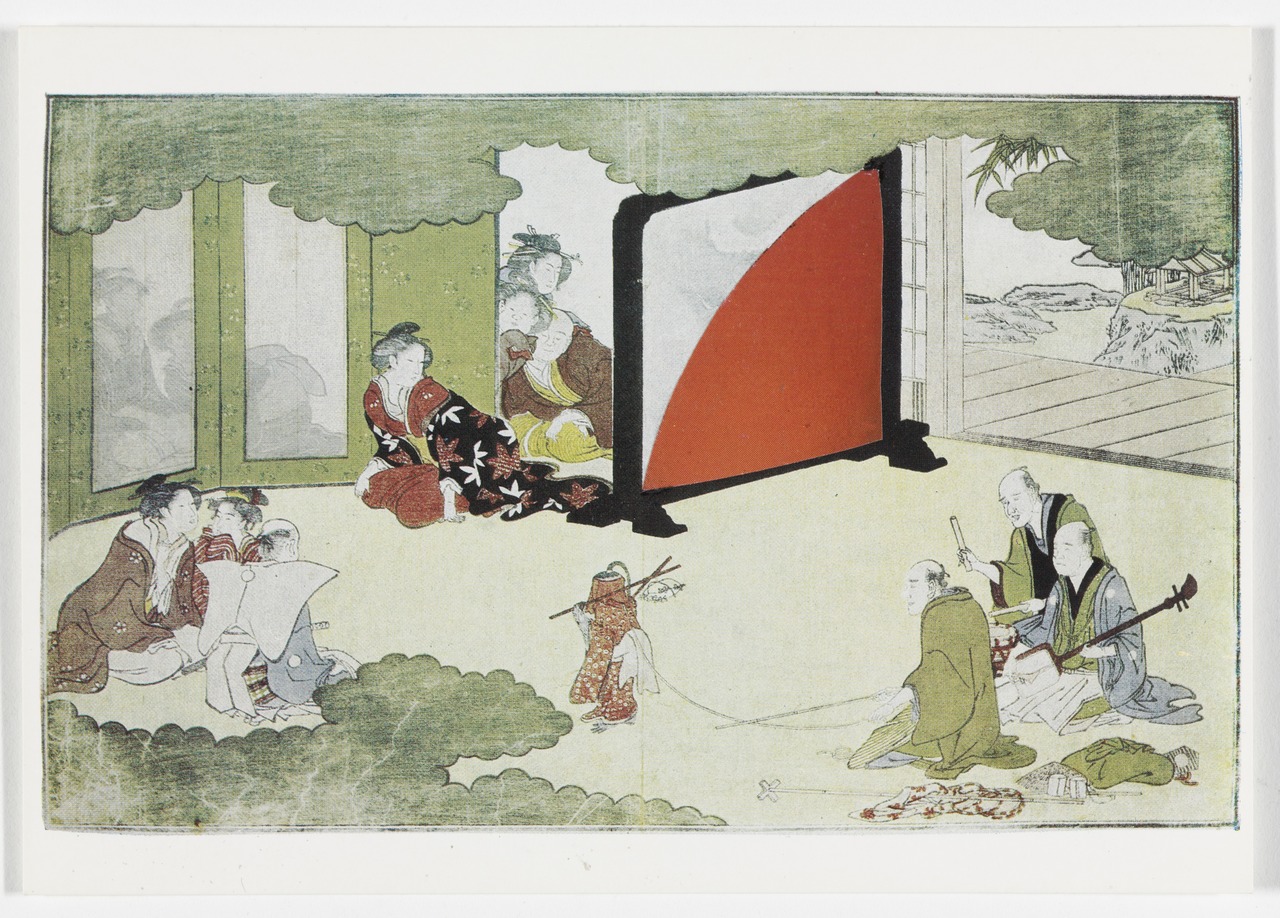

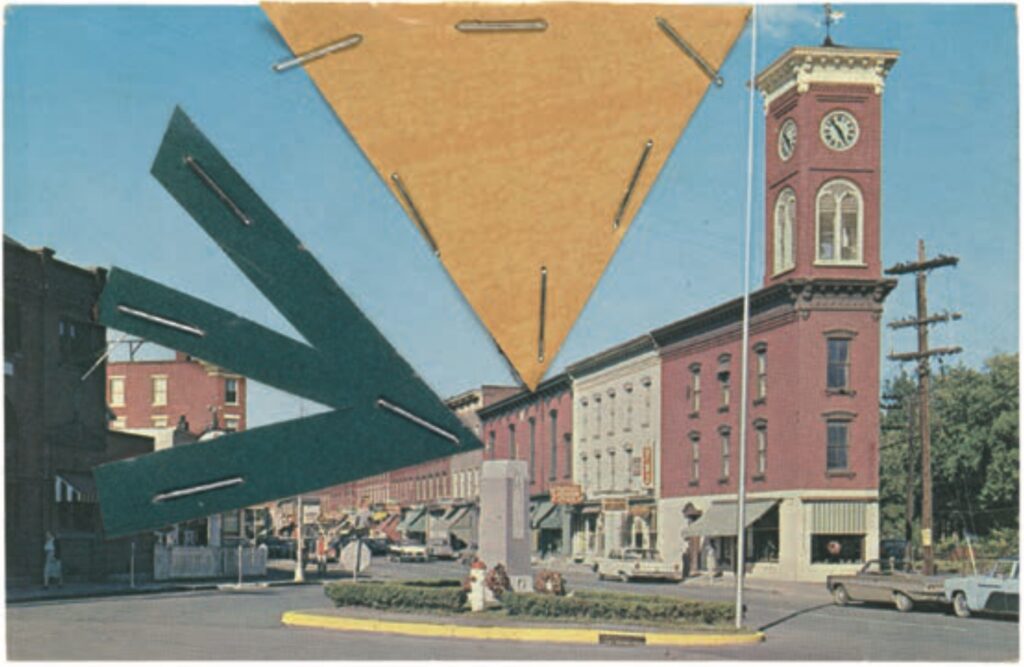

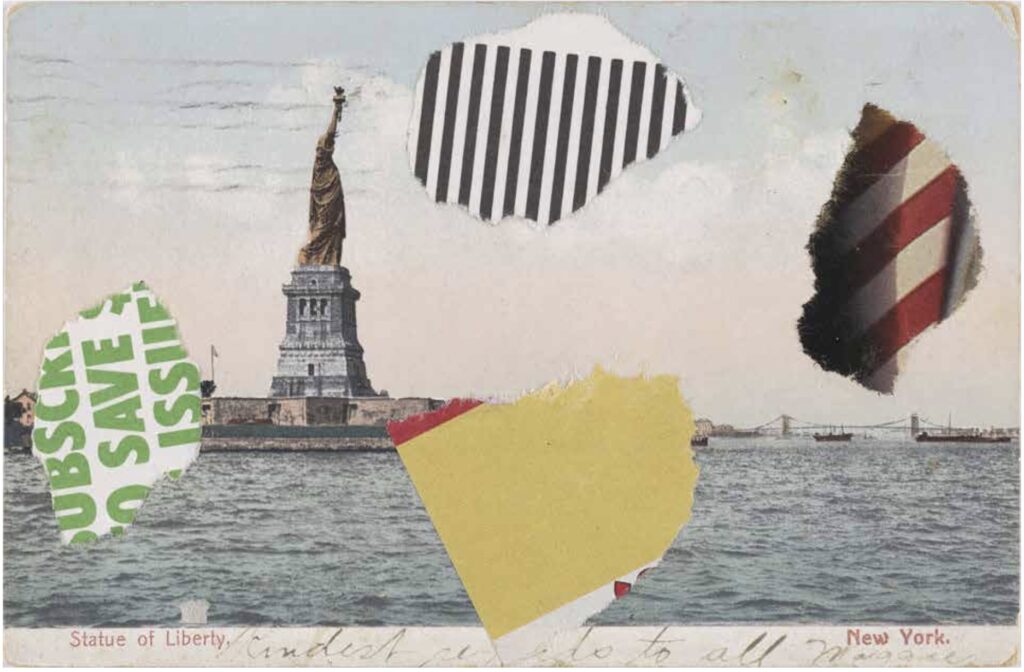

When I first began looking closely at Kelly’s postcards, I was taken by their relationship to his other works, to the way his cut or torn monochrome fragments collaged onto a landscape did or didn’t resemble how his paintings or sculptures were seen in space. They seemed like the perfect inverse of Kelly’s well-established practice: a particular shape, not glimpsed and taken from the world, but made and inserted into it. In that sense they felt related to Gerhard Richter’s overpainted photographs, in which the artist, after finishing his “real” work, captured instances of it with the slightest of gestures by swiping snapshots along his used squeegees.

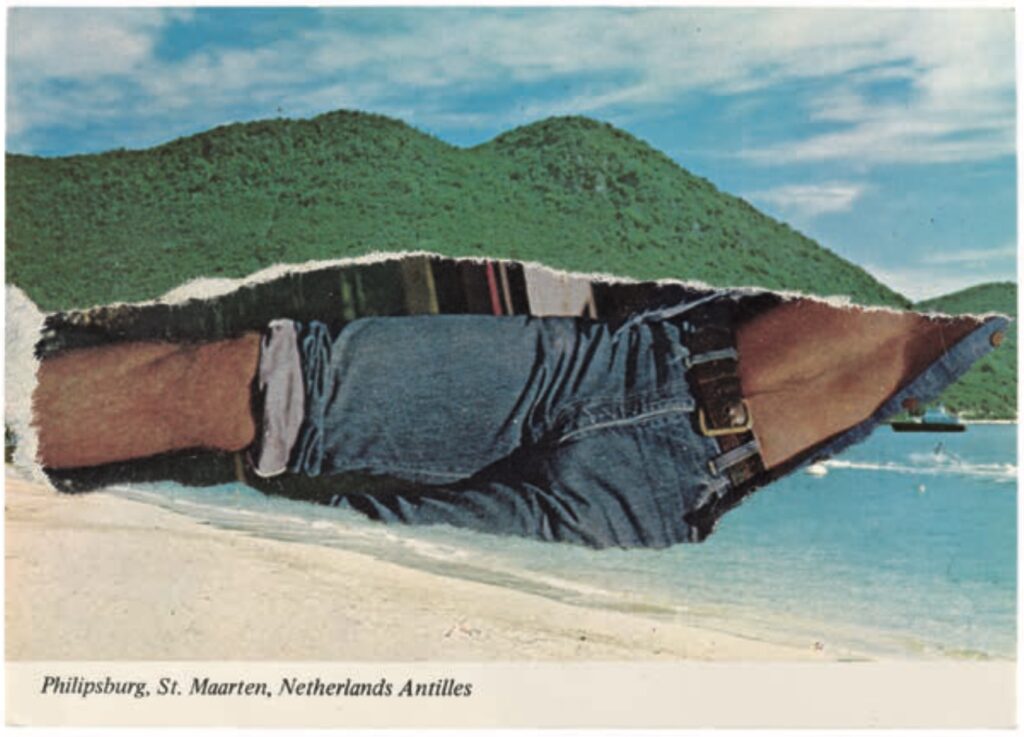

But from living with the catalogue and studying hundreds of Kelly’s postcards, I’ve come to appreciate them as expressions of Kelly’s relationships in his world, not (just) in his work. Like Richter’s snapshots, which he handed out as souvenirs to studio visitors or friends–and which often documented his own travels and the people around him–Kelly’s postcards trace his connections to friends, family, and colleagues. He sent a wave of postcards to show people his new studio in upstate New York [above]. He collaged celebrity photos or sexy body parts torn from magazines onto the beaches of St Martin during his visits to Jasper Johns [below]. He sent them to Shear over the years.

And some he even made from postcards his friends sent him.

Kelly’s painting practice has always felt so singular, even hermetic, in its highly particular way of depicting the artist’s seen world. Beyond Ray Johnson, who Kelly knew since the early 1950s, and the many Mail Art and postcard shows and events around New York in the ’70s and ’80s, which Nayland Blake recalled fondly during a 2021 podcast interview about Johnson, Kelly’s postcard practice underscores how much Kelly was a part of a larger art community, riffing on the world around him, and responding and engaging with the works of others.

Previously, related:

2013: Ellsworth Kelly Postcards

2017: Ellsworth Kelly Dancing Monkey