Walker Evans the photographer also painted. Yesterday, art historian/hero Michael Lobel tweeted a selection of Evans’ paintings from the Metropolitan Museum, which holds the artist’s estate and makes copyright claims on it.

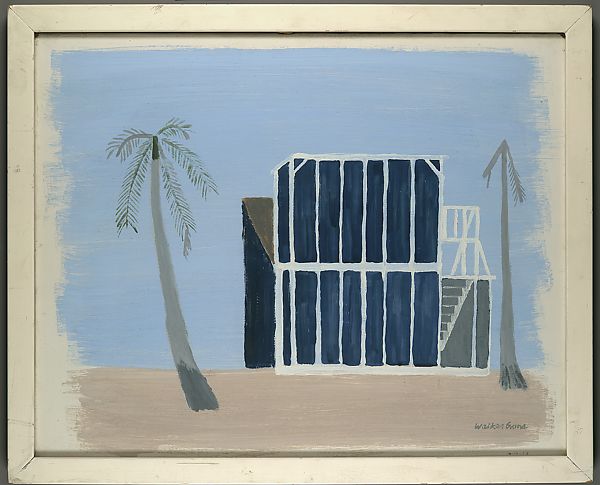

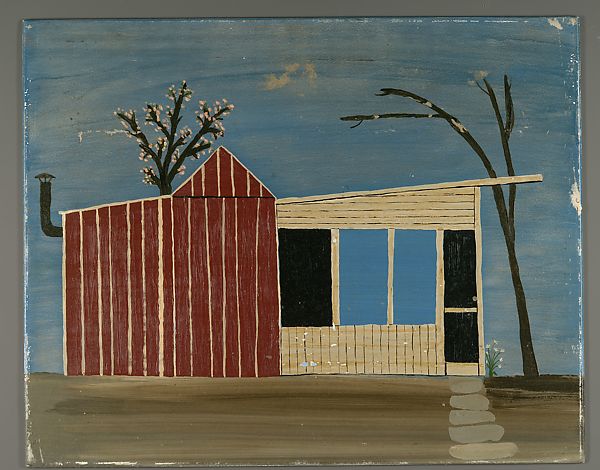

The quickest way to describe Evans’ painting is to say he was in the School of Jacob Lawrence. There are 17 paintings by Evans at the Met, plus photos of one–and probably two–others, plus one by his second wife. All are stylized, spare, and flat, painted in tempera on paper or panels. Unlike Lawrence, who often includes figures and crowds in his tempera paintings, Evans’ are landscapes and homes, and buildings, empty of people.

What was Evans’ painting practice like? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Who knows? I can’t find anything written about it. Evans and Lawrence collaborated on a Fortune Magazine essay in 1948, but Evans was deep in MoMA in the 1930s. He was friends with Lincoln Kirstein; he photographed African sculpture en masse in 1935; and had a show in 1938. So he would have been around in 1940-41 when Lawrence made his epic Migration Series. There’s a painting of Evans painting, by Dorothea Eisner, from 1944 [it’s more legible in a photo of it by Aaron Siskind at Yale than in the Met’s ridiculous thumbnail.] But except for a few which have specific dates written on the back, the Met dates them all to the “1950s-60s.”

Many of the paintings are of beaches, palm trees, and shacks on beaches with palm trees, and so were likely painted during visits to his sister on the west coast of Florida. So was painting an escape, a diversion? Evans also made photographs in Florida of palm trees, shacks–and paintings. Vernacular paintings like signs, murals, and graffiti, were some of Evans’ favorite subjects. Or rather, he often included them in his photographs. So there’s a relationship between his photos and his paintings, or between photography and painting.

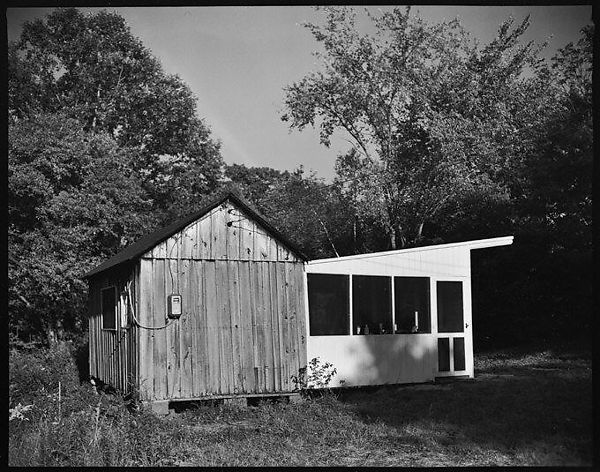

Sometimes Evans made photos and paintings of the same thing, from almost the same spot. The Met dates the photo of the barn/studio above, built for Evans’ first wife Jane Smith, to the 1940s. On the painting of the same barn/studio, Evans wrote the date, Sept-Oct. 1963, eight years after he’d divorced Jane, and three years after he married his second wife Isabelle. On the one hand, it’s right there in front of him, so why not paint it whenever? On the other, that’s a lot of time and life logged between the photos and the painting.

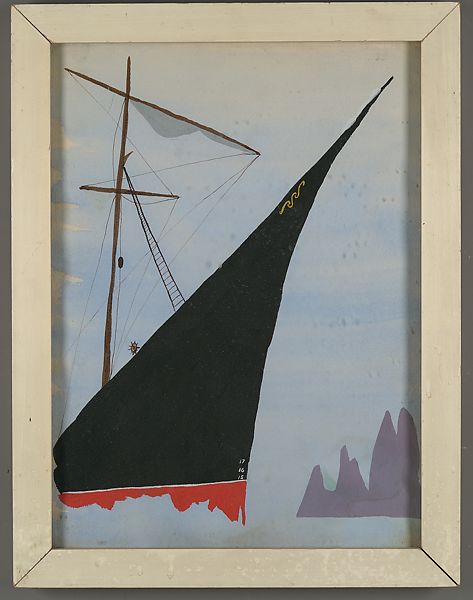

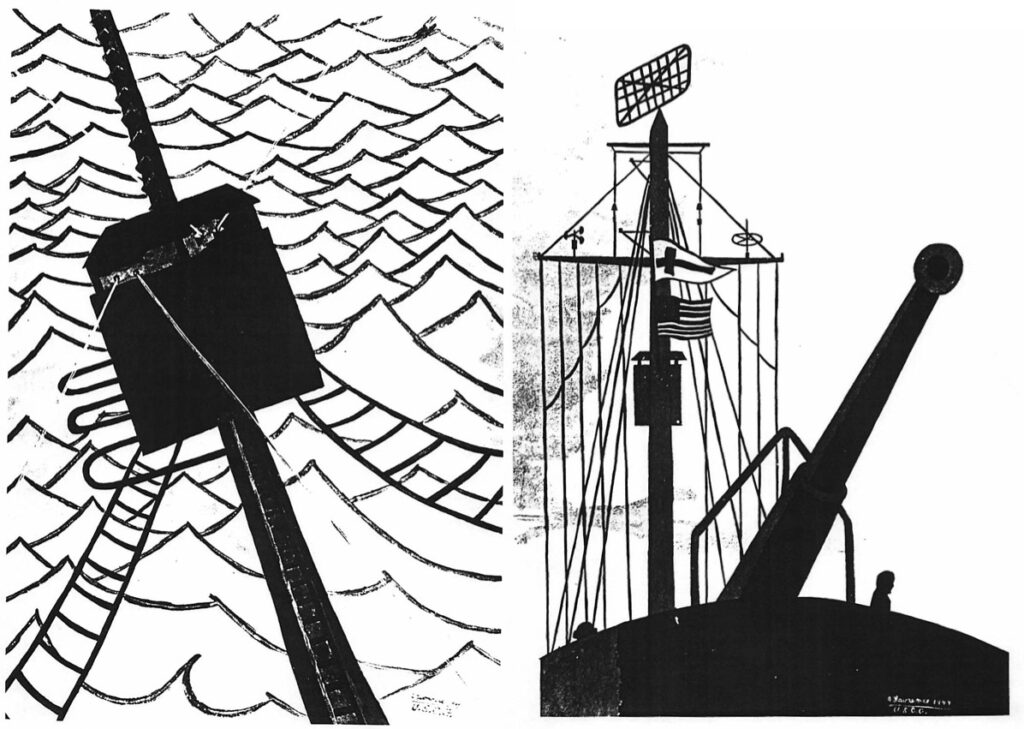

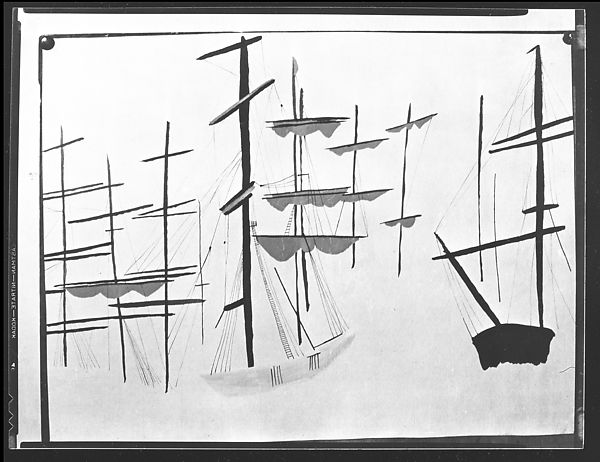

My favorite Evans painting (besides all the rest), the bold, diagonal abstraction of Ship’s Prow is also the most Lawrencian. [The bracketed titles on these are descriptions, not, presumably, the artist’s choice, but who knows?] Ship’s Prow reminds me a bit of a couple of the lost wartime paintings Jacob Lawrence made while serving in the US Coast Guard as part of the first integrated crew of a US military vessel, the repurposed luxury schooner, USS Sea Cloud. He showed them at MoMA in 1944.

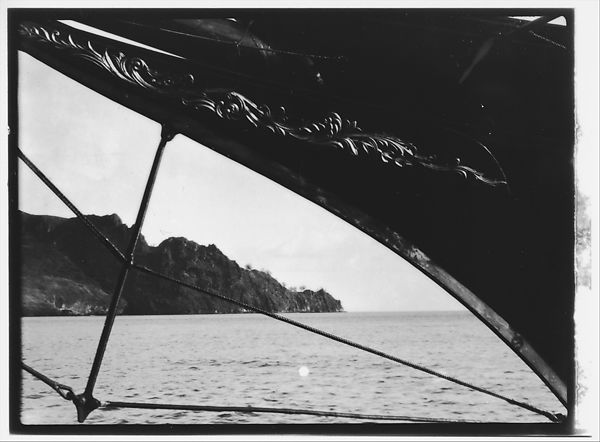

Which is interesting to see alongside photos made in 1932 while on a months-long cruise to Tahiti on another schooner called Cressida. Evans had been invited to photograph the trip by Adolph Dick, a gay, yacht-loving, sugar scion, who chartered the Cressida before buying her sister yacht, Te Vega. They had both been built just before the USS Sea Cloud, and at the same shipyard. Originally named the Hussar, the Sea Cloud was the world’s largest private yacht, created for Marjorie Merriweather Post. All three ships were converted for wartime service and back.

If you paint schooners on tempera, they’re gonna look like that, to some degree. And as interesting as the synchronicities are, it’s really only relevant to fleshing out some dates. Evans’ Cressida/Tahiti photos were a private commission; none were included in his 1938 MoMA show (titled, of course, American Photographs, so) or, for that matter, in 1971. Assuming Evans saw Lawrence’s 1944 MoMA show, when did he even paint that ship’s prow looming over that rocky coastline?

The bow and rigging of the ship looming over the rocky coastline in this 1932 photo with “(Cressida?)” in the description matches archival photos of the Cressida. Meanwhile, that gold scrollwork also matches the bow in the painting, so I think that’s the Cressida, too. Did Evans paint [Ship’s Prow] in the 1950s-1960s, from photos he made in 1932? Did he paint it in the 1940s, after seeing Jacob Lawrence’s work? Did he paint it in the 1930s?

When did he paint this, then? Because if the Met’s date is solid, and the suggestion Ben Shahn painted it is because 1930-33 is around the time he and Evans lived together, then I don’t think it’s by Ben Shahn. But if the Shahn idea leads to the date, then the date’s up in the air, too, because I still don’t think this was by Ben Shahn.

Walker Evans’ paintings will never eclipse his photographs, but they are related, and interesting in their own right. Evans’ paintings of construction sites, buildings, and interiors all resonate with the photos he made. Given these connections, and the prominence Evans gives painting as an element in his photos, it feels like an area ripe for study, and for closer viewing. Yet it seems only two of these paintings were ever exhibited, and none since the Met took over Evans’ estate in 1994. Thanks to @DanielClauzier for pointing out the inclusion of several paintings in the 2017 Centre Pompidou exhibition, which traveled to SFMOMA in 2018. The Pompidou’s video includes another painting of a streetscape, not in the Met’s collection. So maybe they circulated more than we (I) know. [Of course, what I don’t know is filling this website. Sort of the point.]

For four directors now, the Met has treated their vast collection of Evans material as an asset to be controlled, not as an artistic subject to be shared and studied. How Lobel found this handful of paintings in the Photography Department’s 10,000+ unsearchable, unscrollable, unzoomable thumbnails of the Walker Evans Archive is only the first mystery to be solved here.

Previously, related:

Wait, How Could There Be Lost Wartime Paintings by Jacob Lawrence?

Walker Evans’ Beauties of the Common Tool

After After After