Let’s for a moment say we won’t even think about the money. If that seems hard, just imagine that someone donated $7,000 to Parkinson’s research and Sacramento women’s college writing scholarships, and in return, rather than public recognition and a tax deduction, they received Group of Shells and Beach Pebbles.

And then they paid $1,960 to a Hudson Valley auction house to warrant that these “approximately 26” shells and rocks–there are, in fact, 32 shells, 17 rocks, and one item whose rock-or-shell nature I could not determine in the auction house’s display photo–that “[t]his group of shells decorated the fireplace mantle in [Joan] Didion’s living room.”

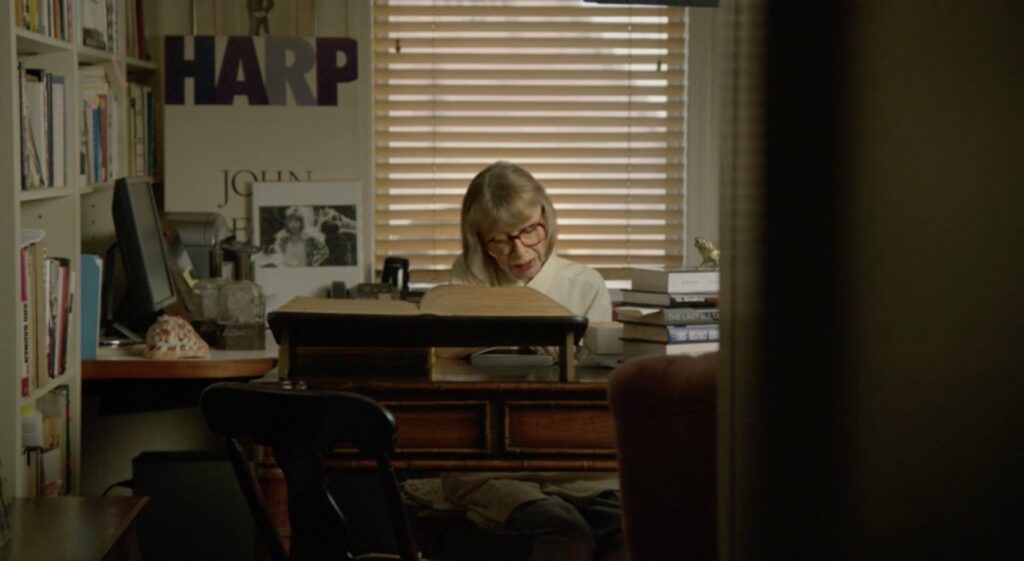

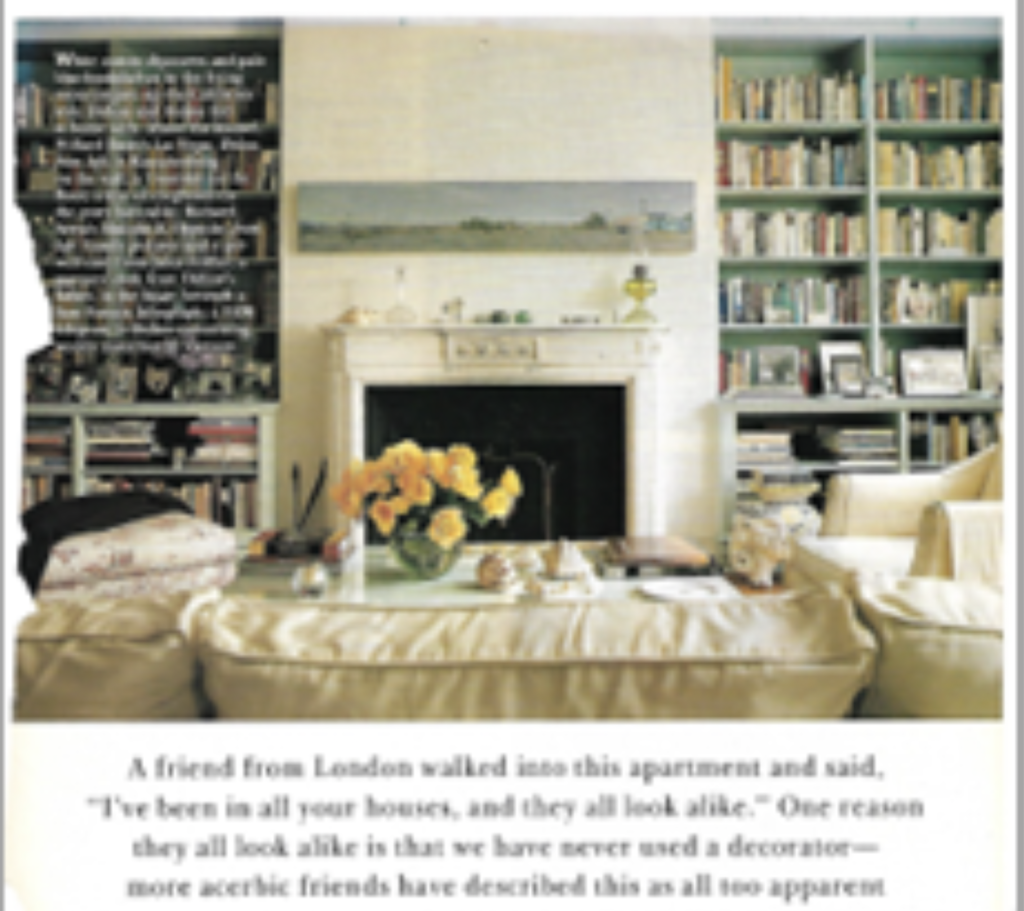

The mantle was the online auction equivalent of the cover lot for the famous writer’s estate sale. The mantle should be familiar to consumers of Didion content; she was photographed in front of it with some regularity. The mantle is, as far as these things go, iconic. Would you want to preserve it? Re-create it? The shells are a necessary part of that, but not all of that, and not only that. Some shells are not there. The configuration changes. In her nephew Griffin Dunne’s 2017 documentary, The Center Will Not Hold, one of the bull’s mouth shells was next to her American Faux Bamboo Writing Table.

In 2006 another of the bull’s mouth shells was in a lacquer tray on her living room table.

And of course, there are many things on the mantle that are not shells. Three Robert Graham sculptures were sold separately. The hurricane lamps were sold in different lots, grouped, not by their location, but according to the shape of their oil reservoirs. The cut glass decanters included sterling bottle labels that were never photographed on the mantle.

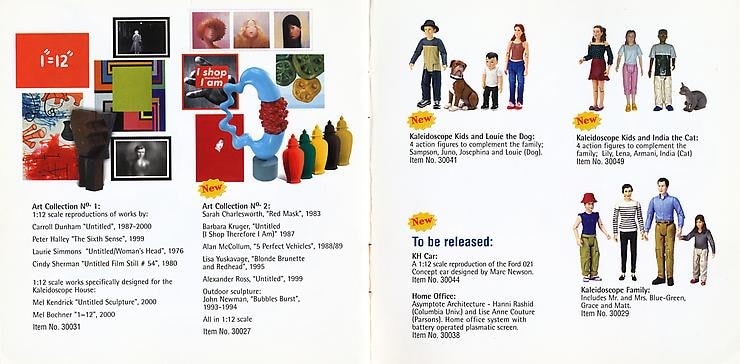

Meanwhile, many objects from the mantle were not in the sale: blown glass floats; a shell-handled letter opener; a small Buddha; a collection of silver objects; a small, sunset-colored painting; a green ceramic sculpture that looks like Kenny Scharf explaining fallopian tubes to Ken Price [that Martin Bromirski identified as by John Newman, a 1993 work titled, Bubbles Burst.]

[OK, sidebar on the John Newman sculpture, which Bromirski identified, and which curator David Platzker also points out was included in an Art Collection expansion pack for Kaleidoscope House, Laurie Simmons’ 2001 modernist dollhouse project. I tried to make sense of the color shifts between the 2006 and 2022 photos, but also the base, and finish, and the scale, all make me wonder whether Didion didn’t have a desktop edition, but a literal dollhouse edition. The dadblogger in me wants to know.]

And then there are objects that don’t appear in Stair’s photo, like the cubic cast glass candle holders, and the miniature Oscar statuette peeking out from behind the whelk.

The whelk feels like an anchor of the mantle installation. Along with the Willard Dixon painting of Las Vegas, of course. Meanwhile, I can find no photos of pebbles on the mantle.

As I tried to understand the implications of Joan Didion’s mantle, I confess, I was only partly successful in not thinking about the money. Just as Didion once skewered the sycophantic retconning of Reagan’s speechifying with political leadership, I was trying to call out the persistent art world conflation of spending money with value or significance. The same mechanisms at work on the shells and pebbles–provenance, materiality, authentication, aura as “contagion magic”, auctions–also shape our relationships to works of art. Sometimes even more so: editioned artworks owned by Joan Didion sold for many times the market price for other editions, the far end of the curve from the Madoff Provenance Project.

More specifically, I was plotting to replicate Group of Shells and Beach Pebbles as a work. But once I started, I had to decide what to replicate: the auction lot? the mantle? the photo of the mantle? which photo of the mantle? Where was the locus of meaning in this folly? As Michael Lobel tweeted when a framed piece of Joan Didion’s mail sold for $41,000, “I honestly don’t understand this world anymore.”

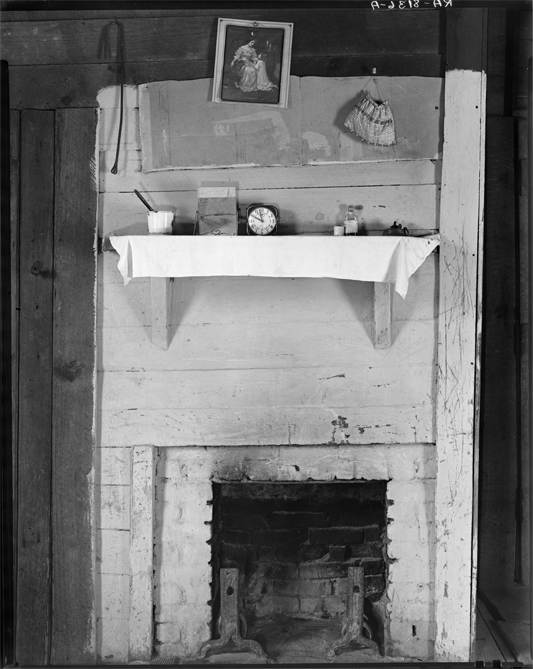

In 2009, filmmaker Errol Morris wrote about “The Inappropriate Alarm Clock,” in a seven-part series for the NYTimes. The subject was Walker Evans’ documentary photos of the Gudger Family’s shack in Hale County, Alabama, which appeared in “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” Morris talked at length with historians and art historians about whether Evans’ photo of the Gudgers’ mantle matched the hyperspecific inventories written by Evans’ collaborator James Agee, and whether the impoverished tenant farmers would even have the one object which Agee did not mention: an alarm clock. Was it perhaps Evans’ clock? And if so, would it impugn the veracity of Evans’ photos, and, perhaps unsettle the foundational assumptions of historical truth in a photographic age?

Which led me back to “The White Album,” and the stories we tell ourselves in order to live. In the screwed upside-down world of the 1960s Didion found herself, she wrote, no longer interested in the stories reported in the news, or the people in them, but only in the picture of them in her mind. “In this light all narrative was sentimental. In this light all connections were equally meaningful, and equally senseless.”

Didion’s mantle has been broken up and dispersed, and money won’t bring it back. Beyond the sentiments they held for friends and family, the objects of Joan Didion’s life became significant because of their proximity to her. Some because she framed them; some because she used them; some because she didn’t; and some because she was photographed with them. In the jingle-jangle afternoon we’re living through now, that makes as much sense as anything else does.