This the 81st anniversary of his birth is the perfect time to say Derek Jarman had Vivienne Westwood’s number, and she knew it.

In Artforum, punk obituarist Derek McCormack tells The Story of The T-Shirt:

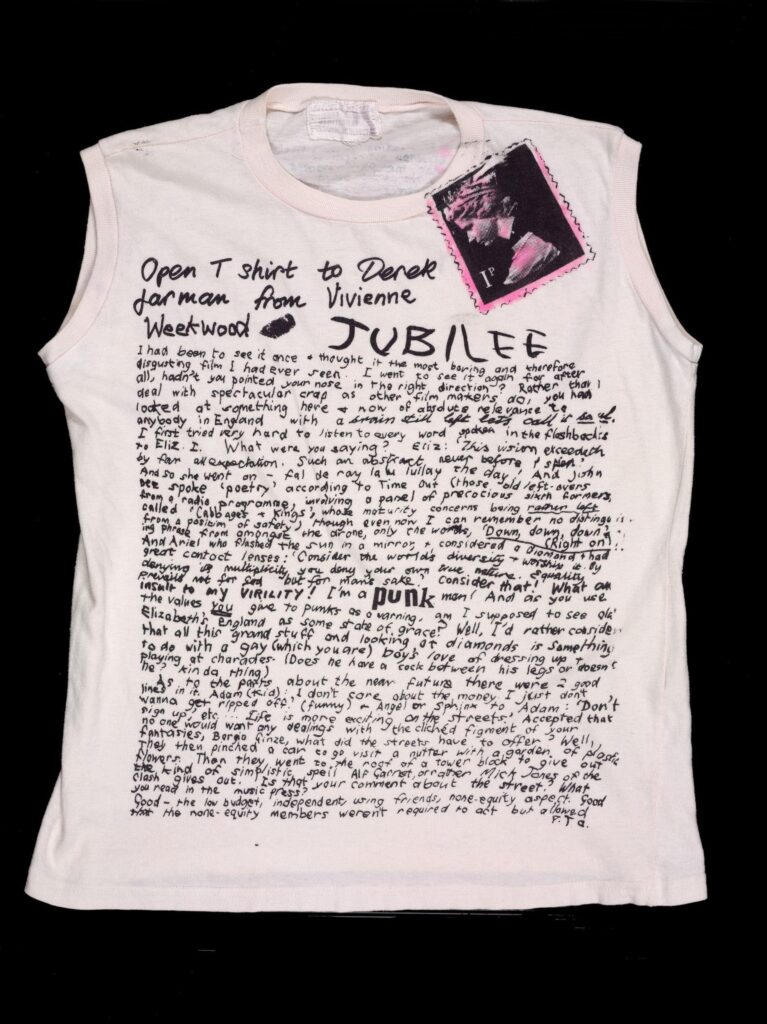

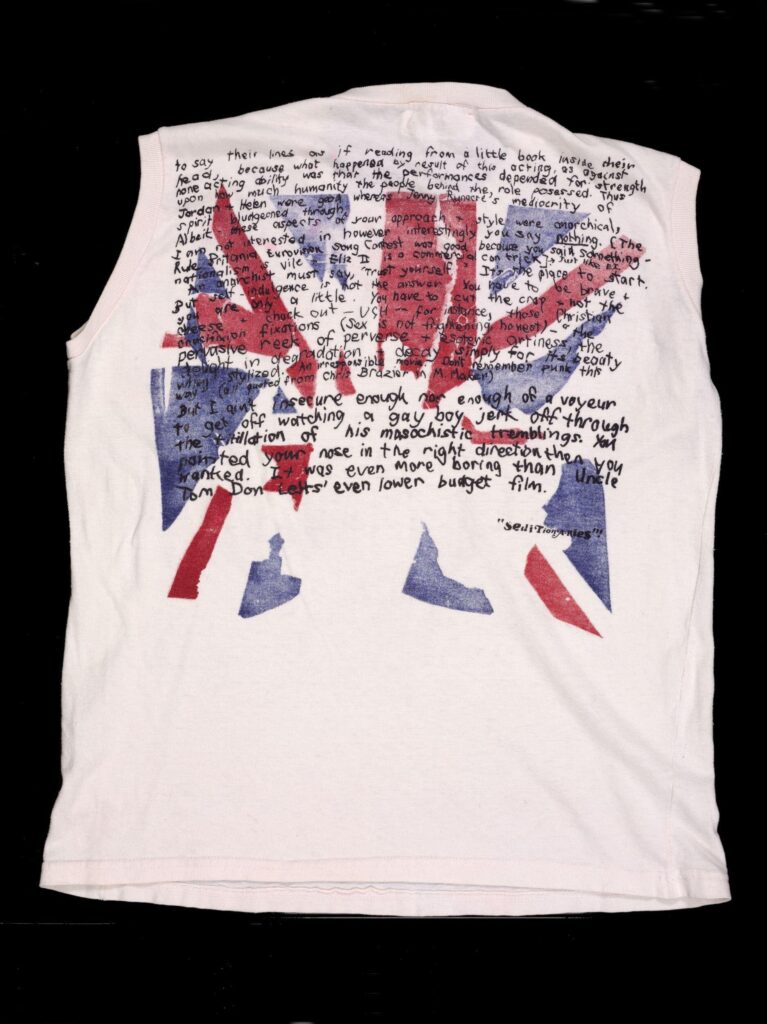

What wicked words she had! What pissy pronouncements! After seeing Derek Jarman’s Jubilee in 1978, she him a “letter” –actually a screed, which she screen-printed onto shirts and sold at the store she owned with Malcolm McLaren: “I had been to see it once and thought it the most boring and therefore disgusting film I had ever seen,” she wrote [on the shirt]. “I’d rather consider that all this grand stuff and looking at diamonds is something to do with a gay (which you are) boy’s love of dressing up & playing at charades. (Does he have a cock between his legs or doesn’t he? Kinda thing)…”

You could say the words on the shirts were there to communicate something, but you’d be wrong. This wasn’t communication; it was spectacle. The T-shirt is a lousy medium for messaging: you can convey a slogan, but it must be concise–passersby can’t stop you to pore over what you’re sporting. So what McLaren and Westwood did was perverse–they did way too much and went way too far…”

So Westwood writes 700 words calling Jarman the worst things she could think of–boring, nostalgic, uptight, low budget, and gay–but that’s not important; it’s just spectacle.

What’s important is this: The shirt was dressed in words. The fashions Westwood and McLaren made at their store were the first to meld literary text and textile. They did it because–unbelievably–nobody else had. They did it to see what could happen, to see if words could fuck up clothing and if clothing could fuck up words, if one could damage or destroy the other –so punk! They did it with the thought that new words and clothes could be created from the destruction–wasn’t this their credo, that one should destroy culture? Wouldn’t this mean that they could be both creators and critics of a new culture–fashion design as criticism and criticism as fashion design?

Jarman didn’t call out just any nihilistic, exploitative, fascism-loving punk in Jubilee; this was Westwood and McLaren’s punk, the new culture they were creating, and they were not amused.

As historian Jim Ellis noted, Jarman modeled the punk intellectual/ goosestepping lip syncher Amyl Nitrate after Westwood, and the fascist mobster/producer Borgia Ginz after McLaren. [The actress Jordan was a Jarman friend who worked in Westwood’s shop, Seditionaries, and managed Adam Ant, who is also in the film, and who was ripped off by McLaren in real life.]

Jubilee‘s punk found family all wear text-on-textile, RAF surplus jumpsuits handpainted with a quote that could be about a society perilously in thrall to spectacle: “I hope they are watching. They’ll see. They’ll see and they’ll know, and they’ll say, ‘Why she wouldn’t even harm a fly.'” Which is, in fact, Norman Bates’ Mother’s voice in his head in the closing scene of Psycho.

After a long day of murder, firebombing and castration in the city, all the punks but one end up chilling at Ginz’s country estate in Dorset–and watching Nazi rallies on the telly with literal Old Man Hitler.

Jarman saw that Westwood & McLaren’s punk wasn’t new culture, but an inextricable facet of the one culture England had. Turns out it’s the same one that packaged rebellion on a T-shirt on a band on TV, and that ushered Margaret Thatcher into power the next year. The one that rebelled [sic] by revealing you hadn’t been wearing underwear when you got knighted by the Queen.

The diss T-shirt Westwood sent to Jarman is as much an admission as an embrace of the cynical punk culture Jarman portrayed. The last line, the racist callout of “Uncle Tom Don Letts’ even lower budget film” as boring gives the game away: in 1978 Letts released The Punk Rock Movie, a documentary of iconic bands’ early performances which he shot while DJ’ing at The Roxy. Letts’ film was released in June 1978, four months after Jubilee, and eight months after McLaren’s own Sex Pistols film project–to be directed by Russ Meyer from a script by Roger Ebert–had collapsed. With competition looming for their movie no one would see, Westwood & McLaren figured they could get more from punk selling T-shirts no one would read.