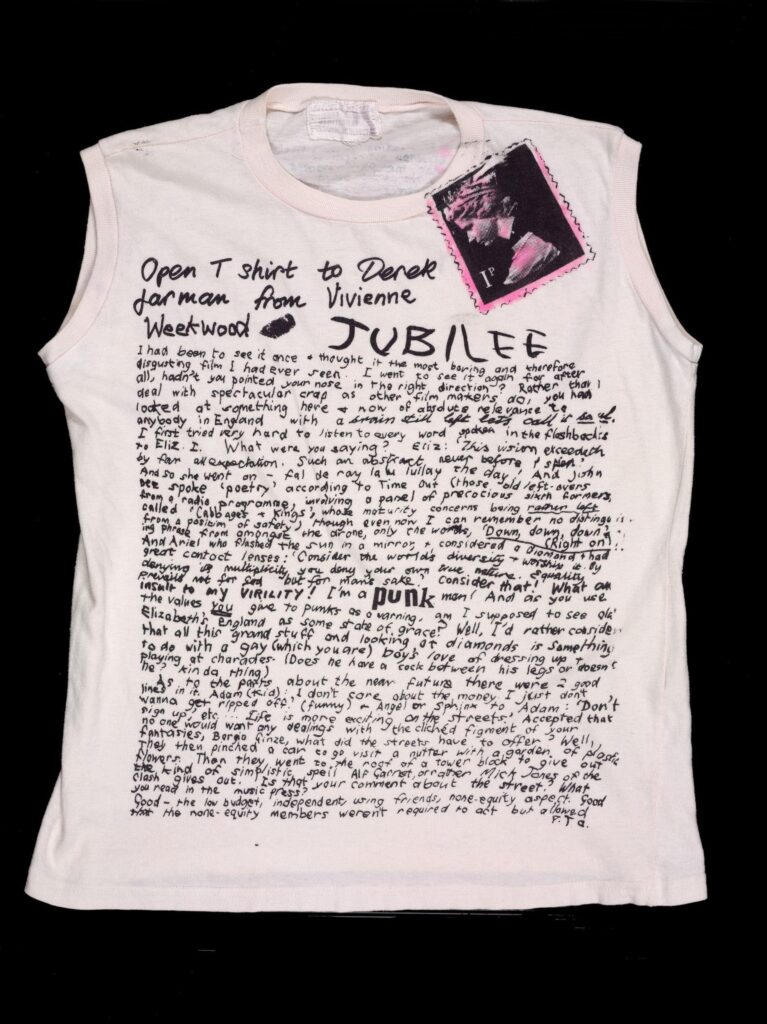

It’s an accident of timing that I’ve kept thinking of Derek Jarman as a filmmaker with a painting hobby. He was still alive when I saw my first Jarman film, Edward II, and when Blue blew me away. And I felt I knew his story, so I’ve been slow to read his early autobiography, or other books about him; my job was to just catch up and see all his earlier films. It didn’t help that I didn’t really like the paintings shown after his death. His notebooks were more relevant.

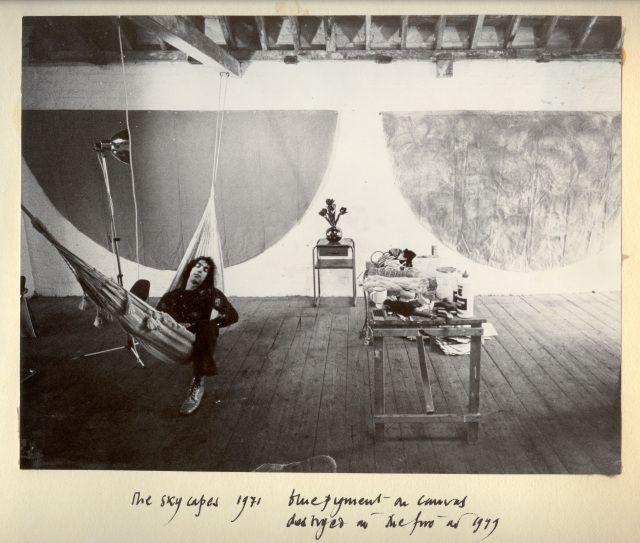

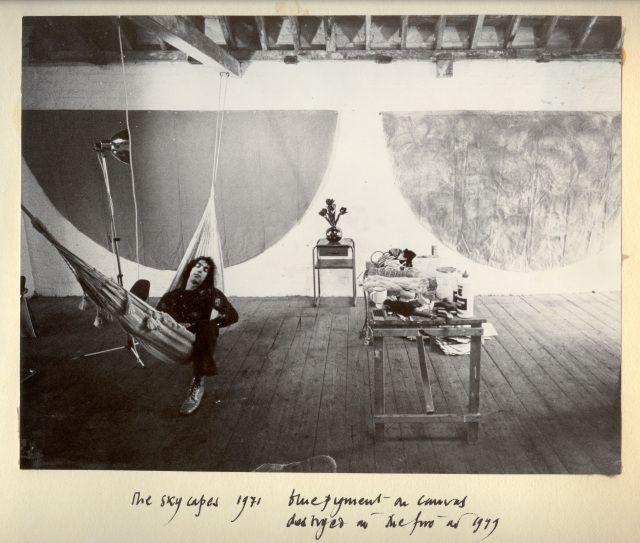

But I just saw this photo which changed all that. I wasn’t 100% wrong, but I was close: Jarman’s painting was more formative and influential-and interesting-than I realized. The photo’s from 1971, and it is captioned in Jarman’s dramatic hand:

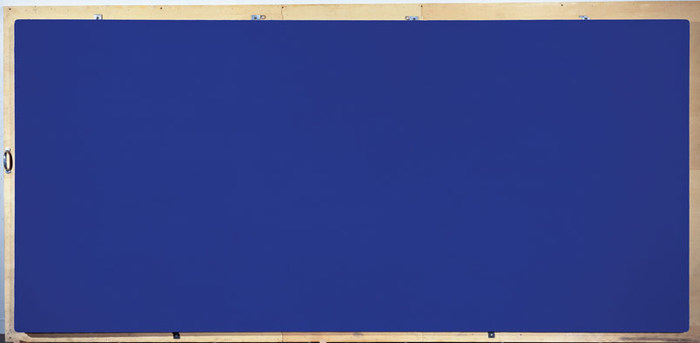

“The Skycapes 1971 blue pigment on canvas

destroyed in the fire in 1979”

Skycapes has been a Google dead end, or rather a cul de sac for this caption. But capes, capes is where it’s at. In his 1999 biography of Jarman Tony Peake traced the form and concept of the cape to Jarman’s theatrical work, particularly his ideas for a production of The Tempest:

Capes are both practical and sensual, especially when cloaking nakedness. They are geometric: if hung on the wall, they form a half circle. They have mythic overtones: by donning a cape, the wearer can effect a transformation. These qualities, particularly the latter, had considerable potency for Jarman, who now set about working and reworking this new possibility until the capes he produced-and began to hang on the walls of his studio-no longer resembled design, but approached the condition of painting or sculpture.

Now the timing’s a little confusing, because Jarman made a film version of The Tempest in 1979. But Peake notes the project had interested Jarman for years. And Jarman made a clear, laminated cape scattered with dollar bills [or pound notes, maybe?] for the 1969 production of Peter Tegel’s surrealist play Poet of the Anemones. Peake said the two met at Lisson Gallery.

And the walls of Jarman’s riverside loft were lined with extraordinary capes when filmmaker Ken Russell visited and asked him to design the sets for The Devils, a project that consumed most of Jarman’s waking hours in 1970. Exhausted and dissatisfied by the film project and wary of commercial film industry entanglements, Peake wrote, Jarman “chose to concentrate on his capes, some of which he now began to paint, in two main colours, black and blue, but mainly blue: ‘simple sky pieces to mirror the calm.'”

That quote’s from Jarman’s own 1984 memoir, Queerlife, which was published in the US with the title Dancing Ledge in 1993:

1971. The Oasis

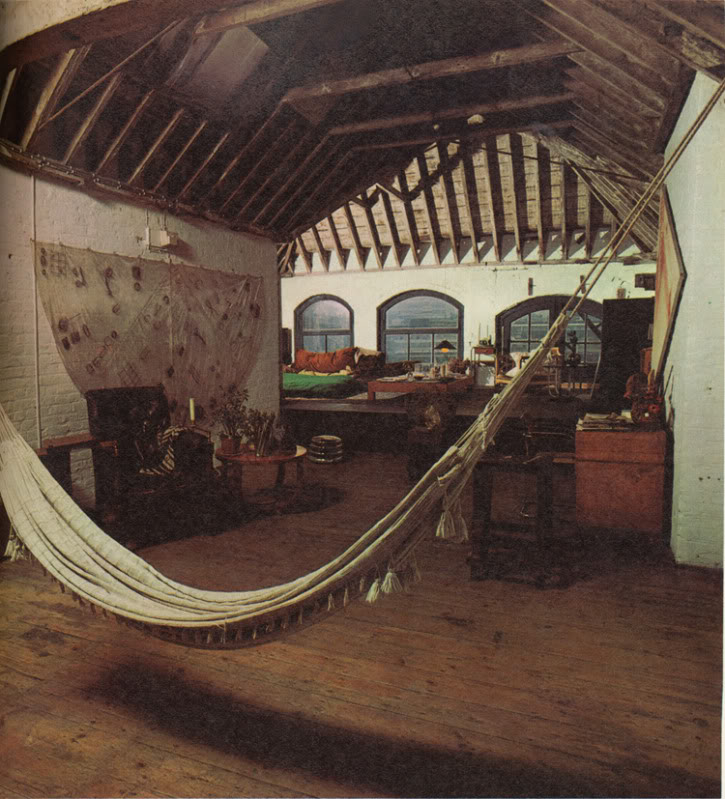

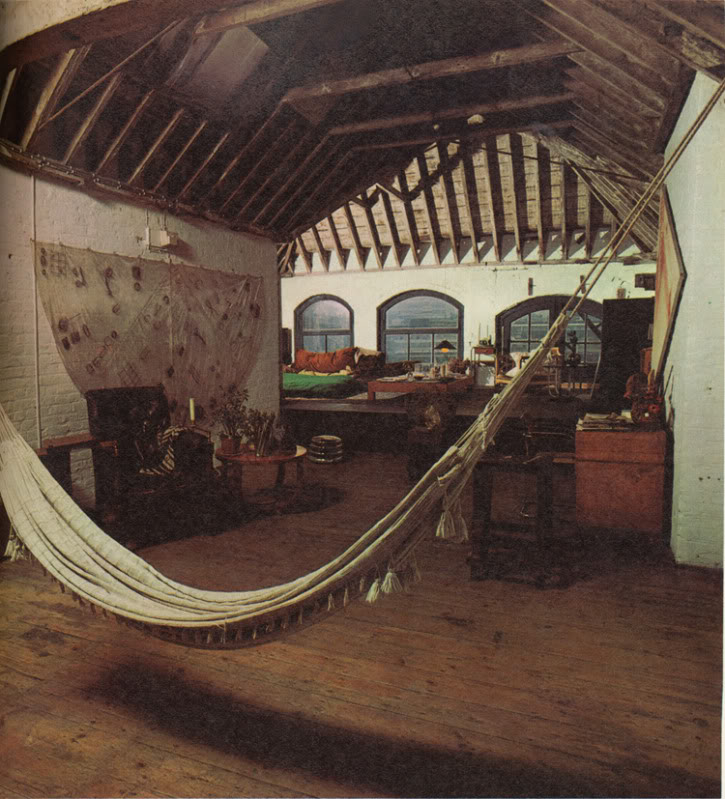

The intervening year was spent painting a series of blue capes, which hung on the walls at Bankside. They were simple sky pieces to mirror the calm that returned after the frenzied year of The Devils. That summer was an idyll, spent sitting lazily on the balcony watching the sun sparkle on the Thames. When I wasn’t painting I worked on the room and slowly transformed it into paradise. I built the greenhouse bedroom, and a flower bed which blossomed with blue Morning Glories and ornamental gourds with big yellow flowers. On Saturdays we gave film shows, where we scrambled Hollywood with the films John du Can brought from the Film Co-op- The Wizard of Oz and A Midsummer Night’s Dream crossed with Structuralism. There were open poetry readings organized by Michael Pinney and his Bettiscombe Press. Peter Logan perfected his mechanical ballet, and MIchael Ginsborg painted large and complicated geometrical abstracts.

An oasis paradise indeed, replete with all the essential elements of Jarman’s subsequent accomplishments. Which is, at least, how he himself saw it when he looked back from 1984.

Here is a 1971 photo by Oberto Gili of Jarman’s amazing Bankside loft, the top floor of a 19th century wheat warehouse. Which had the floors, the ceiling, the views, the space, but not the plumbing or the heat (thus the greenhouse bedroom). There’s the hammock from the first photo, and a laminated cape which had tools, weeds, and detritus retrieved from the abandoned waterfront. [How far do the similarities go between Jarman and other gay pioneer artists like Robert Rauschenberg? Jarman would’ve spit at the comparison; in a 1984 interview at the ICA he slammed Jasper Johns for being a tool of the CIA. #freequeerstudiesdissertationtopics]

Henri Matisse cutout designs for priests’ chasubles for Vence Chapel, 1951, photographed in his studio surrounding a Picasso painting, by Helene Adant. image: tate.org.uk

In Ken Russell’s telling of their first cape-filled visit, Jarman “was getting ready for an exhibition called “Cardinal’s Capes.” It’s a phrase which turns up nowhere else, but which makes me think of Henri Matisse, who designed amazing chasubles for priests to wear in his chapel at Vence. They began as cut-outs, and were translated into fabric, and changed with the seasons.

In 1970-71 Jarman had two solo shows, including capes, at the then-new Lisson Gallery, but he grew to disdain the gallery system. He also hated Pop and bristled at working in the long shadow David Hockney cast over the London art scene. He opened his studio for his own damn show in 1972, which Peake says was disappointing [though he sold some work and celebrities turned up for the opening, so what greater success could art hope for?]

He included new capes made from black lacquered newsprint [Rauschenberg?] in a 1984 mid-career exhibition at the ICA. [He was 42.] And in that public talk, he described funding his early features by selling paintings and raising money from his painting collectors.

Anyway, are there any Jarman capes left to be seen? I can’t find any. In 2015, the ICA screened Jarman’s super8 documentation of his 1984 show for the first time, but there’s no visual trace online. And as the caption to the original photo mentions, his earlier capes, including what he called his Skycapes, were destroyed along with Jarman’s and others’ studios in 1979.

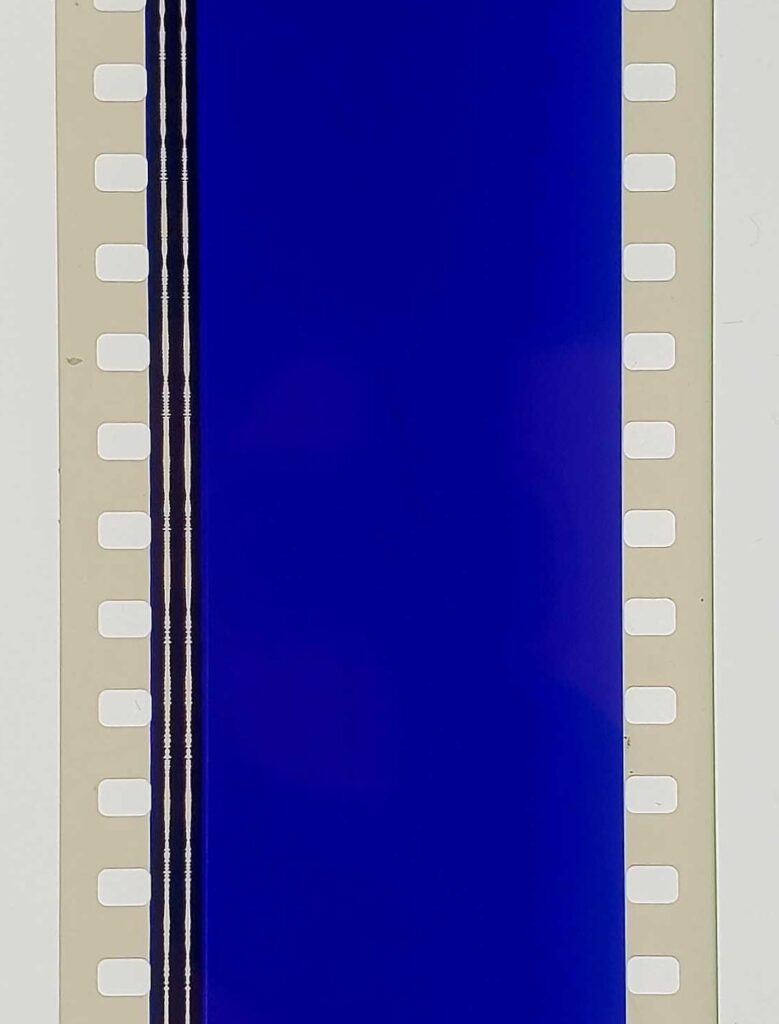

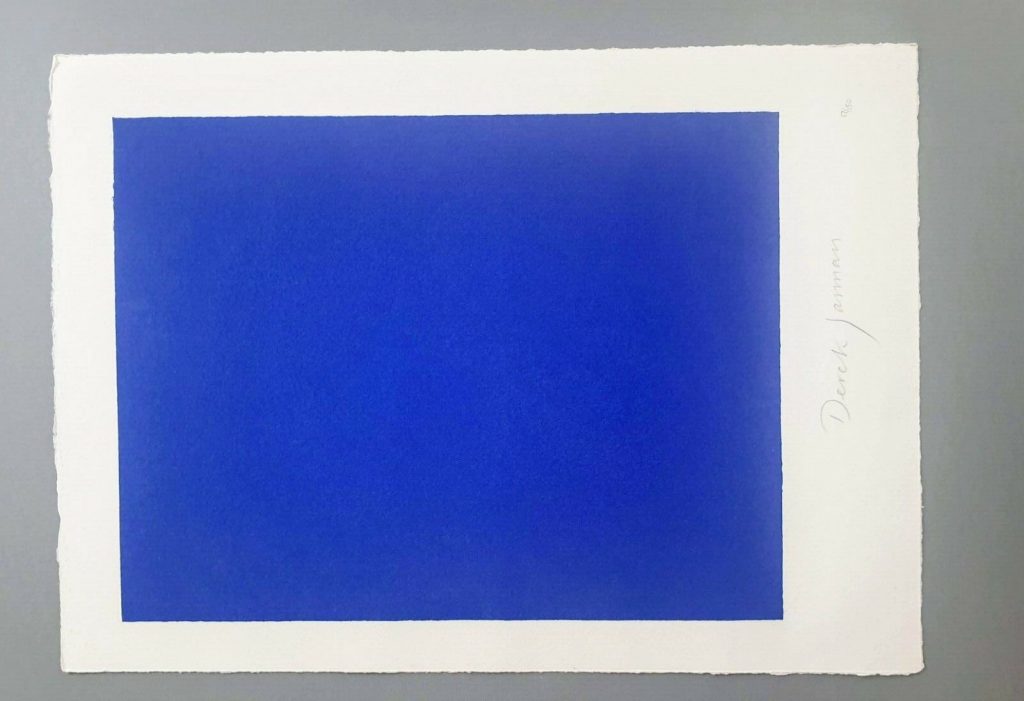

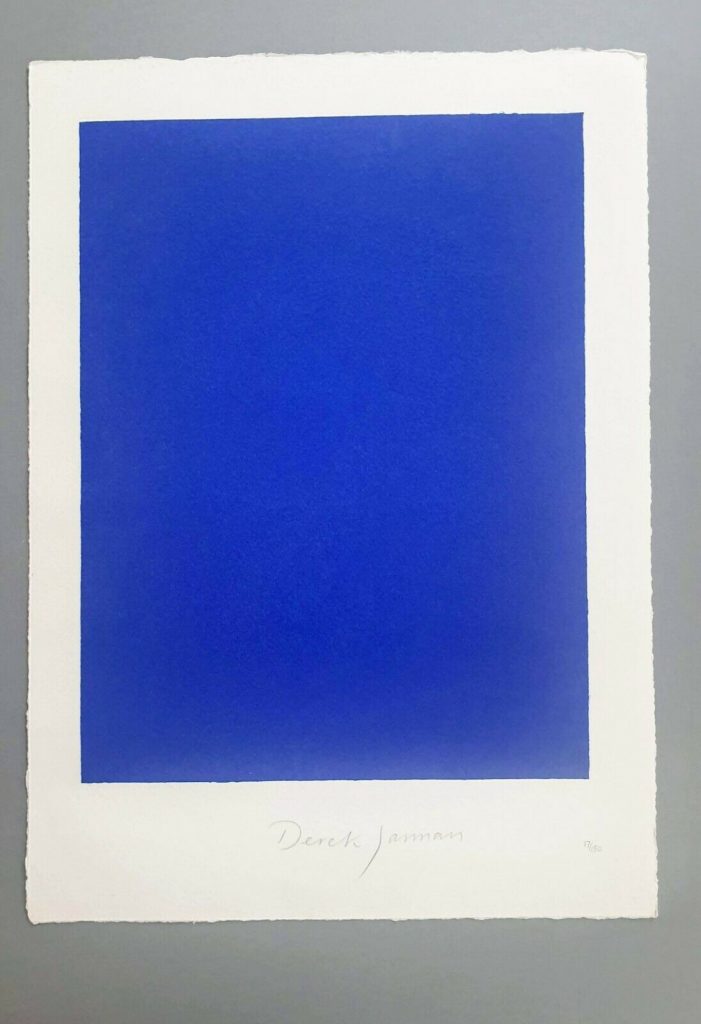

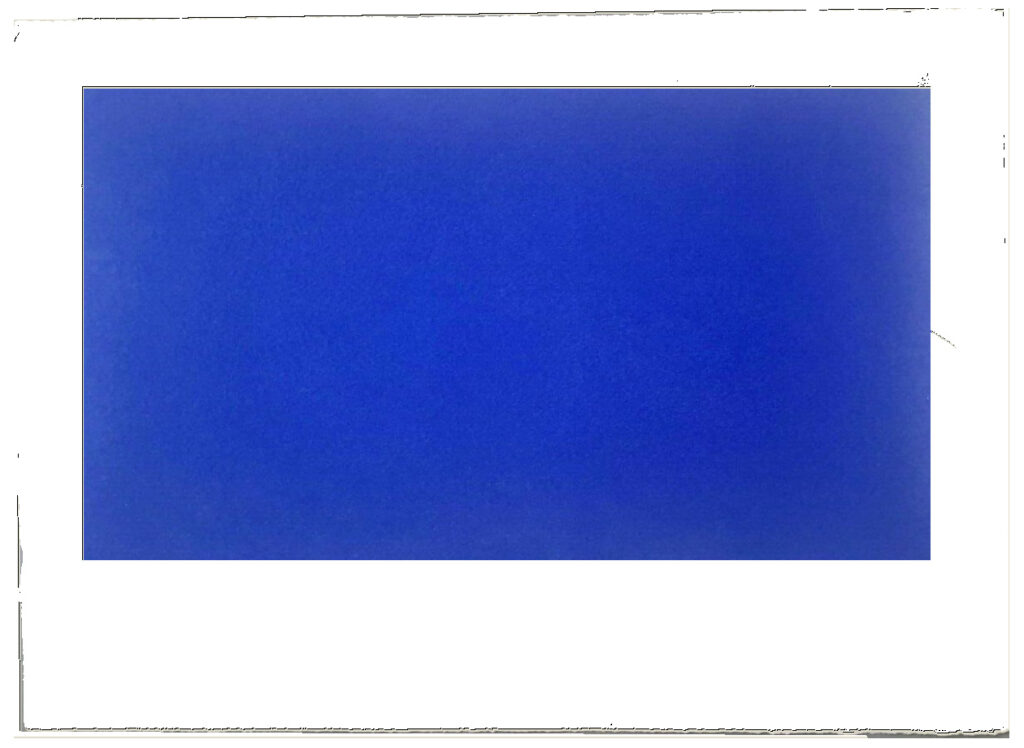

By retrospectively titling them with the sky, and using the term “blue pigment” instead of paint, Jarman also seems to be linking the capes to one of his clearest references, Yves Klein. Klein the outrager who said his first artwork was signing the sky. Whose International Klein Blue appeared throughout Jarman’s notebooks in the 80s. Jarman filmed an IKB monochrome painting and projected a loop of it for a 1987 live poetry/music performance event he called Bliss, which became his last, greatest film, Blue, in 1991-3.

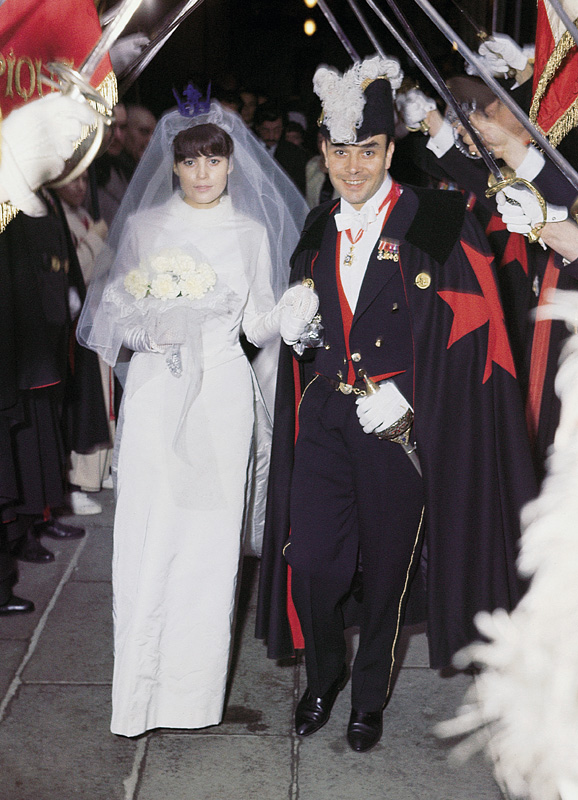

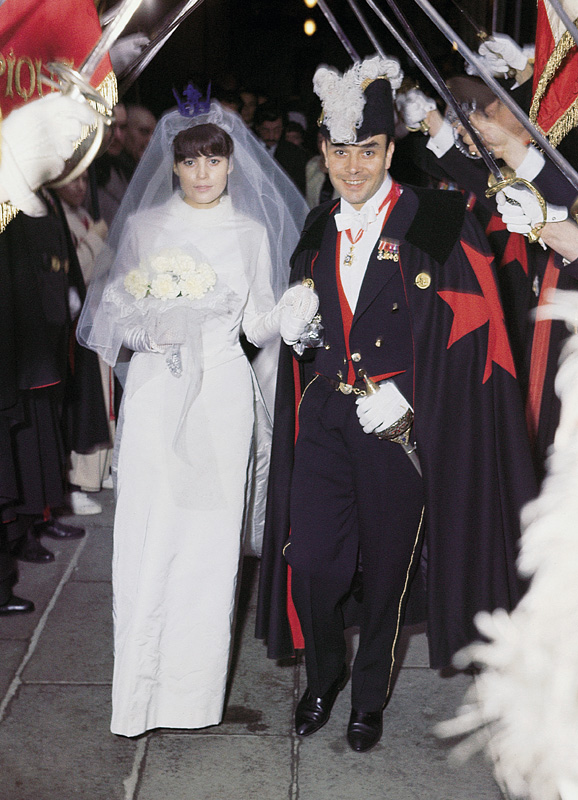

Here is Klein at his wedding on January 21, 1962. Rotraut Uecker is wearing an IKB crown, and he is wearing a cape emblazoned with a Maltese cross. They are processing through the raised swords of the Chevaliers of the Order of St. Sebastian. So at least I know what my dissertation will be about. But first we have to solve the problems that there are almost no Jarman Super-8s online; that Klein’s wedding was filmed, and that’s not around, either. And then, of course, all these destroyed capes. There is a lot of work to do.

Previously, 2013: International Jarman Blue

2004: It’s not just Derek Jarman’s Blue

2002?:

As I lay typing

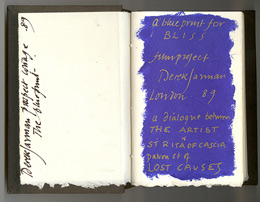

When Blue was still called Bliss, back in 1987, and was a Klein-related companion film to The Last of England, Jarman filled a notebook with dialogue, poems, and IKB monochrome paintings. The Bliss Book and other Blue-related preparatory and archival material will be in

When Blue was still called Bliss, back in 1987, and was a Klein-related companion film to The Last of England, Jarman filled a notebook with dialogue, poems, and IKB monochrome paintings. The Bliss Book and other Blue-related preparatory and archival material will be in