This morning Michael Lobel brought some art historically significant mug shots to the social media discourse, including one of my long-time favorites, Andy Warhol’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men, a grid of 22 mug shots mounted on the facade of the New York State Pavilion Theaterama at the 1964 World’s Fair. Within two days of its unveiling, the work drew complaints from officials, and the 25 panels were painted over with silver aluminum paint.

It seemed so bold and promising. Bettmann dates the release to the press of the image above to April 15, 1964. The original caption gives the piece a different title, but it also had World’s Fair officials—and Johnson—on record explaining and promoting Warhol’s project—for one day:

A Place at the Fair. Flushing Meadow, N.Y.: Photos of New York City’s 13 Most Wanted Criminals -resplendent in all their scars, cauliflower ears and other appurtenances of their trade, unabashedly adorn masonite facade of the New York State Pavilion at the World’s Fair. The display an arrangement of official Police Department “mug shots,” forms a 20×20 foot mural mounted on the pavilion. Philip Johnson, a designer of the pavilion, said the mural is “a comment on the sociological factor of American life.”

Media criticism of the mural came instantly, followed somehow by the decision to overpaint it. One of the most sharply cut gems in Larissa Harris’s 2014 Queens Museum’s exhibition marking the 50th anniversary of Thirteen Most Wanted Men in 2014 is the letter from Warhol dated 17 April, two days after the mural’s debut, confirming the Dept. of Public Works’ authorization “to paint over my mural in the New York State Pavilion in a color suitable to the Architect.” The Architect, of course, was Philip Johnson, the nazi MoMA trustee Governor Nelson Rockefeller picked for the job. Harris’s catalogue infers that Warhol and Johnson discussed the color to be used—silver, like the freshly painted Factory—but I read the letter as very deliberately ascribing the overpainting to Johnson.

Johnson told the press this was all Warhol’s idea, that he didn’t like how the mural had been installed, that it was definitely not pressure from above (i.e., Rockefeller and/or World’s Fair capo Robert Moses), and that Warhol wanted to reinstall something new. Only the last one was true, and it never happened.

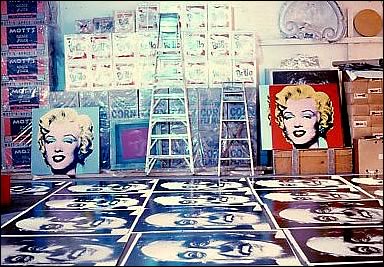

It did not register with me until today that Warhol was still working on a replacement mural four months later, in August, right between two now-iconic gallery shows: the Brillo boxes, which opened at Stable Gallery on April 21st, one day before the World’s Fair; and the Flowers, his first show at Castelli, in November.

When I posted about Warhol’s rejected and destroyed grid of Robert Moses portraits in 2014, it was to lay the groundwork for myself to remake them. Minds as great as Andrew Russeth and several others had tried over the years to find out who made the commemorative mosaics the NYC Parks Dept installed in 1996-98. I’ve waited all this time, then, to see someone correct the mosaic’s caption, and properly identify the source of the photo Warhol used. I guess I will do it myself.

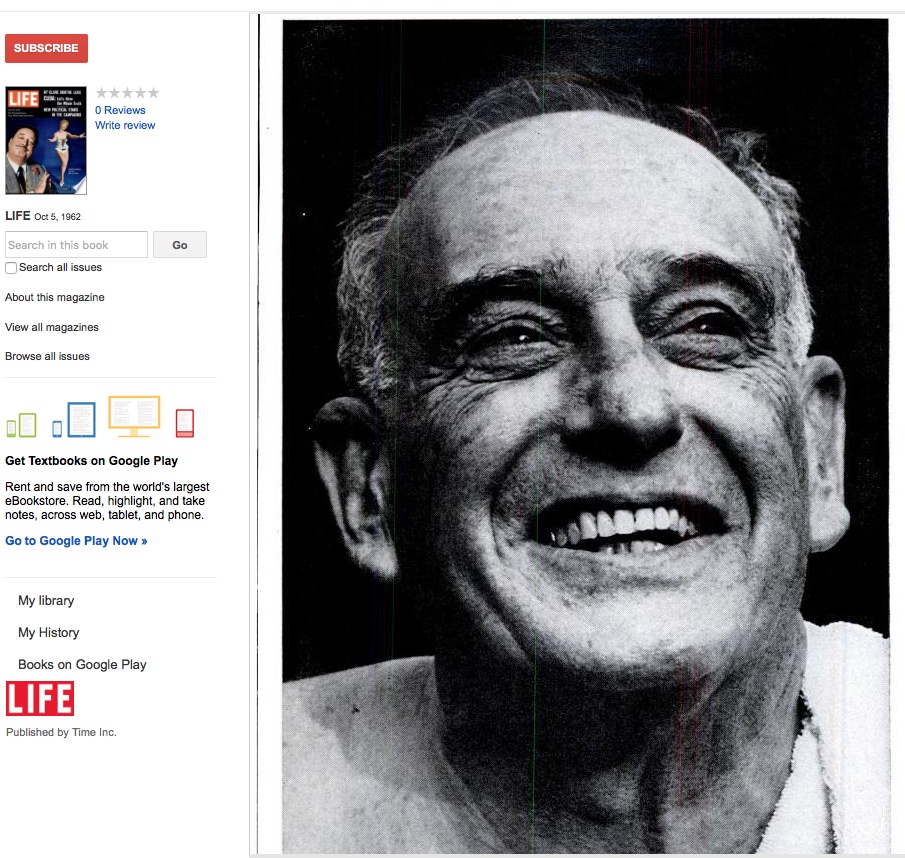

Warhol took the image from a three-page feature on Robert Moses in the October 5, 1962 issue of LIFE Magazine. The quotes Moses gave LIFE reporter Jane Howard about such topics as traffic, urban planning, democracy, The American System, and hors d’oeuvres [?] ran next to a half page photo of a shirtless and dripping Moses emerging from the surf near Jones Beach.

It turns out LIFE photographer Bob Gomel followed the 73-yo Moses to several places for photos on August 1, 1962: Moses landing on Fire Island in his trademark helicopter, surveying the bridge he was building, talking about the highway he wanted to destroy the island with. In his office. In a boat. And in the sea, with an unidentified boy. Getty Images has 15 pictures from the day, including Gomel’s headshot of Moses, topless, with a towel on one shoulder, the other bare. [He swam for Yale and Oxford, LIFE reports.]

Johnson rejected Warhol’s provocation, obviously. By that point, the World’s Fair’s poor attendance and economics were clear and weighing on Moses’s reputation. It’s what came after that intrigued me today.

photo: Peter Warner via Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation

Lobel’s question—which I’d never seen posed, much less answered before, even in the Queens Museum’s extensively researched show—is why was the work covered with a tarp after it had already been painted over? I can’t figure out why, but I have some idea about when.

I haven’t seen it discussed anywhere, but I’m pretty sure the photo with the tarps that Richard Meyer included in his 2002 book on censorship and homosexuality, Outlaw Representation, was taken while the Fair was closed, between October 1964 and April 1965. There are no leaves on the trees, those guys are in light coats, and those cars are parked all over the Avenue of the United Nations, one of the Fair’s main pedestrian thoroughfares.

detail from a photo via BoweryBoysHistory

Meanwhile, we know it stayed up. Warhol was interviewed in front of the silver painting in July 1965: “I don’t believe in anything, so this painting is more me now,” he said. “Why?” “Because silver is so nothing. It makes everything disappear.” Silver’s not the only thing. The photo above shows the Avenue empty of cars, but also the trees full of leaves, which obscured Thirteen Most Wanted Men [and completely blocked James Rosenquist’s World’s Fair Mural on the right.]

The few historic images and anecdotes of Thirteen Most Wanted Men inevitably fail to convey the full experience over time of the work on display. Warhol kept at the project for months, even after being instantly betrayed by his patrons. Maybe the question to ask is not who censored the mural and why, but who placed it, publicized it, and freaked out over it and made it a problem in the first place?

Previously, related: On Warhol and the World’s Fairs

Images and ideas I’ve been thinking of