And bought some stuff. And made some stuff. The press release discussed it in the context of hashtag collector, and Roberta Smith called it “a resonant portrait of the United States.” But Robert Gober’s exhibition at Demisch Danant, “Cows at a Pond,” felt like the self-portrait of an artist trying to live and work ethically in a present where the injustices and suffering of history repeat themselves. So I guess they’re both right.

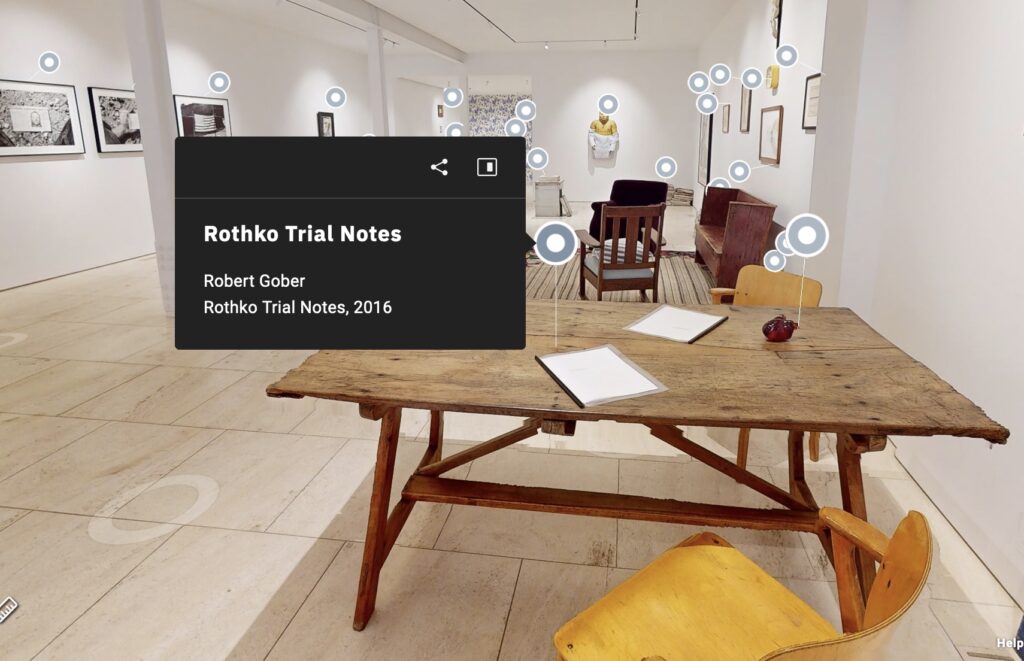

I sat in Gober’s chair to read his notes—unfinished and unpublished, except, of course, for putting them in a show—of attending the art forgery lawsuit against Knoedler Gallery. One important observation was the purported shock at the naked fraud perpetrated by the “venerable” gallery, a term Gober remembered from the 2000-2001 coverage of the price-fixing crimes of two “venerable” auction houses: Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

There was the EMERGENCY NO PARKING sign from the Mall on January 6th, 2021, and photos, published in Gober’s 2001 Venice pavilion catalogue, of clippings from The New York Times defending homophobia in the wake of Matthew Shepard’s murder.

Turns out Gober bought this tiny, anonymous, and alluring painting of the Washington Monument on January 6th, 2022.

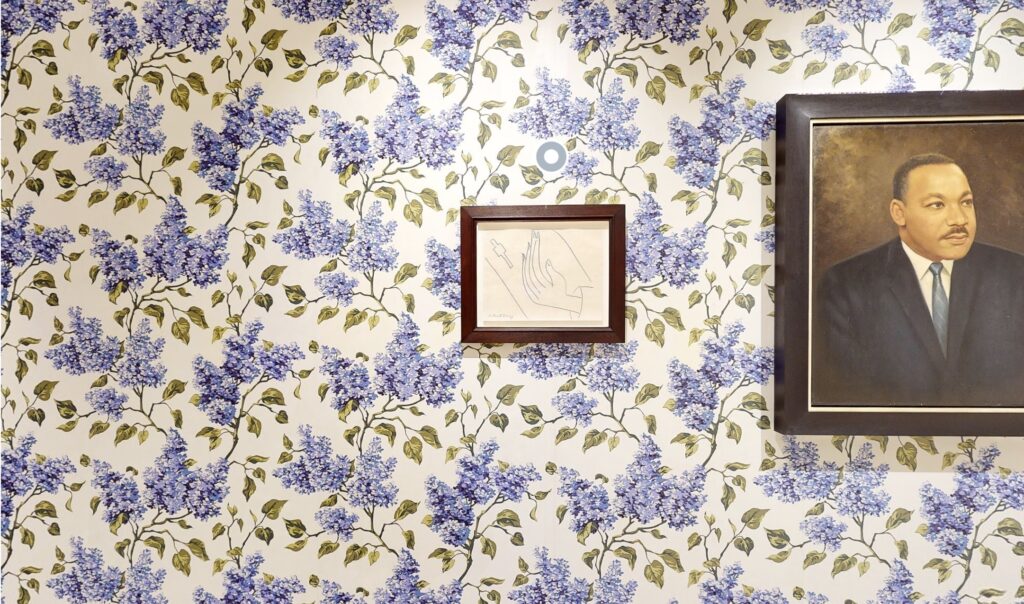

The longest note in the checklist is for the wallpaper, screenprinted by hand: “In the Roosevelt Cottage on Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Canada, there is a lilac patterned wallpaper that Eleanor had recreated from a design that she remembered from her childhood. We then recreated that, taking some liberties, for our dining room in New York. R. G.” It is also not just wallpaper, but a work, Untitled, from 2013.

Which all reminded me of the June 2001 NY Times article about his US Pavilion, which discussed his epic 1997 installation at MOCA of a Madonna pierced by a culvert: “To Mr. Gober, that Madonna was as autobiographical as it was iconographical to the church.” And which quoted Roberta Smith ranking the MOCA installation alongside Matisse’s Vence chapel as “great works of modern religion.” The tumult of the MOCA project—which eventually ended up, miraculously, at Maja Hoffmann’s Schaulager—led Gober to leave his dealer, close his studio for a few years, and focus on a house renovation project. So a self-portrait of things accreted in the spiraling gyre of history it is, then.