In June 1844, the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, where they were being held in jail for treason. [Joseph, who in addition to being the founding president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was also the mayor of the Mormon-dominated city of Nauvoo, had destroyed the printing press of an anti-Mormon/anti-Smith newspaper and declared martial law. This led to his arrest for treason against the state of Illinois, but somehow none of that is particularly important to this blog post.]

The bodies of Joseph and Hyrum were brought back to Nauvoo, 22 miles away, in hastily constructed coffins of oak lumber. They were buried in a Smith family home, then moved to another site seven months later.

The blood-soaked wood from the temporary coffins was cut up and distributed to a few church leaders and friends of the Smiths by their widows, to be made into canes. When the bodies were reinterred, clippings of the Smiths’ hair were collected, distributed, and incorporated into the heads of some of the canes. These canes became known as Canes of the Martyrdom, and in a religious culture that officially eschews such things, they have become ersatz relics.

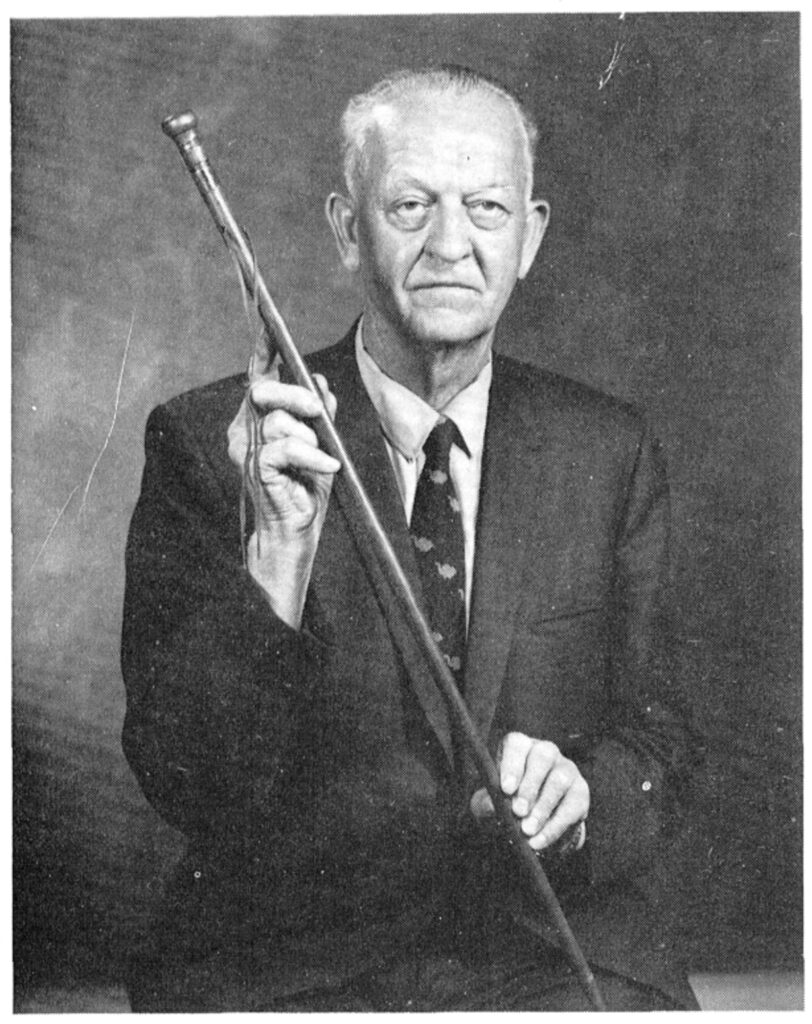

Like the relics of other faiths’ martyred saints, the canes were seen as conduits for divine healing or protection. In more secular terms, they also functioned as IYKYK symbols of authority via proximity to Joseph Smith. [At least three of Smith’s prophet successors had canes, including John Taylor, who was in the Carthage jail, was shot, and survived. That’s his son Richard Taylor holding what’s known as the Dimick Huntington Cane in the photo above.]

[In an unpublished manuscript discussed in a 1981 BYU Studies Journal article on the canes by Steven Barnett, Taylor claimed the canes represented an oath taken by close associates of Joseph & Hyrum Smith to avenge their deaths. There is no historical evidence or corroboration of this interpretation.

Within the families of the recipients, the canes served as symbols of a quasi-hereditary calling. At least one cane remained with Smith family members who did not recognize Brigham Young as Joseph Smith’s successor, and did not follow him out of Nauvoo. The church founded with Joseph Smith III and his descendants as prophets kept the cane on display in the Smith historical home site in Nauvoo; this site was among several the church, now called the Community of Christ, sold to the Salt Lake church. It’s not clear if the cane conveyed.

Not that they needed it. At least four canes are already on view in Salt Lake City: two at the church’s own historical museum, and two at the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum. The number of canes is unknown, as is the number of purported or spurious canes.

While in other situations, I might have marveled at this obscure piece of Mormon folklore and let it go, I have just been thinking about that stick of David Hammons. And that supposed walking stick of Frederick Douglass and/or John Brown. And the forensic fetishization of the fragments of wood beams from Thoreau’s cabin at Walden. And the foundation for all of that was the project gathering the scattered fragments of George Washington’s old coffin, which were apparently given out by his family as mementos. So when I find this reverential woodworking in my own cultural backyard, I guess I can’t look away.

Episode 2: Joseph Smith’s Martyrdom Canes [Angels and Seerstones]

Of Healings, Canes, and Gardens [bcc]

“The Canes of the Martyrdom,” Steven J. Barnett, BYU Studies Journal, 1981 [byu]

Previously, related: Oh right, there was the lost maquette for a giant memorial to the Smiths inside the Salt Lake temple for a while