Well that took five minutes.

The erasure or diminishment or downplaying or whatever of the gay, AIDS, and immigrant identity of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and those identity characteristics as vital context and reference in which he made his work in the 1980s and 1990s, is real and should be called out and resisted. It happened publicly and messily at the Art Institute. It happened similarly at Zwirner. It happened in subtle, coercive ways art historians and critics called “oppressive.” But addressing it’s not a question of either/or, but of both/and, as Johanna Fateman skeeted, and expanding the meaning of the work, the contexts in which it resonates, and the changes in the world around it every time it’s exhibited should build on the artist’s achievement in its original moment, not replace it.

Anyway, this debate is not advanced by the current outcry over the show at the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always To Return, because the claimed erasure is not happening. I’m not going to litigate Ignacio Darnaude’s impassioned but wrongheaded, blinkered, and inaccurate article condemning the way “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), a 1991 candy pour is presented. Its connection to AIDS is not erased. Felix’s connection to Ross is not erased. And as I walked out of the Felix galleries, past the James Baldwin and The Voices of Queer Resistance exhibition next door, and on through the permanent collection install, I have to say, there is no museum anywhere doing more of the work right now than the NPG & SAAM.

So. Here is the way “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is presented.

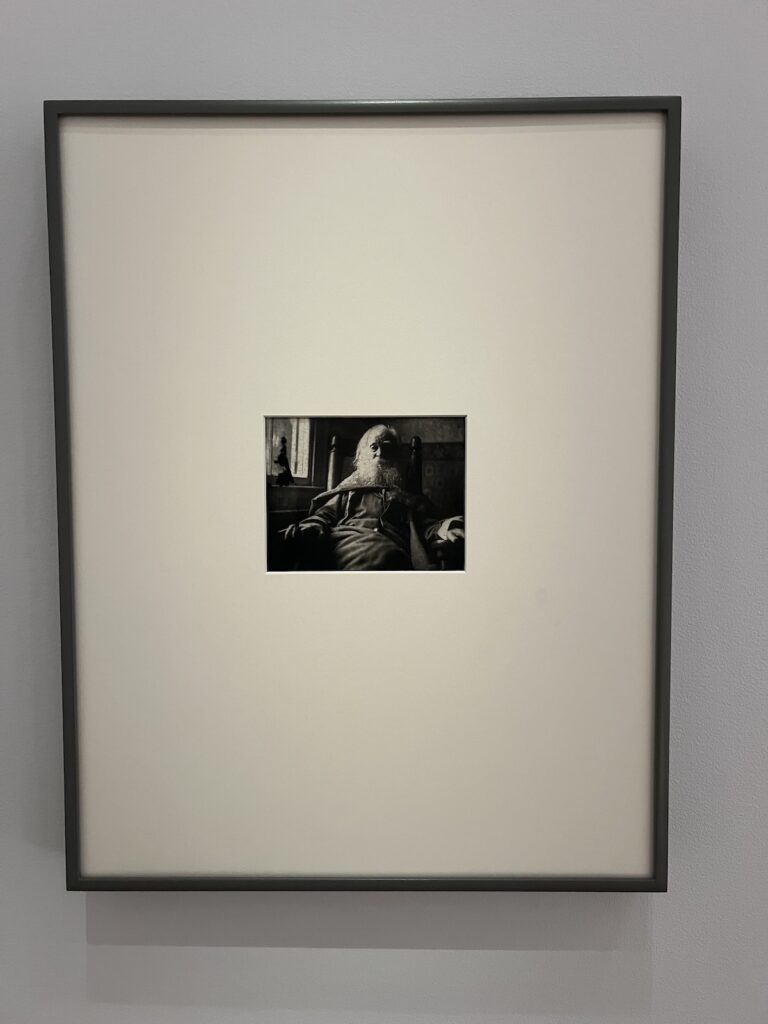

There are three works in a small, dark gallery: “Untitled” (Leaves of Grass), a 1993 light string from a private collection (it originally belonged to Eileen & Michael Cohen); an 1891 Thomas Eakins photo of Walt Whitman; and “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), a 1991 multi-colored candy piece from the Art Institute of Chicago. Two of the bilingual labels for the works have extended text that discusses all three works. The label for the candy pour is just a label, including the “Ideal weight: 175 lbs” and a nut allergy warning. [Another candy piece, is piled in the center of the adjacent gallery, “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad), also 1991 (he died that year, too), and also “Ideal weight: 175 lbs.” That’s not discussed here, though it does complicate simple reading of the ideal weight concept, and it gives context for the decision to vary the candy pour along the wall instead of in a pile.]

The installation of these three works makes specific points about queer history, caregiving and death; about change over time; about these two artists’ connection; and about the specific history of this building and this institution, where Whitman worked, and where two of these works were shown together before. Here are the texts:

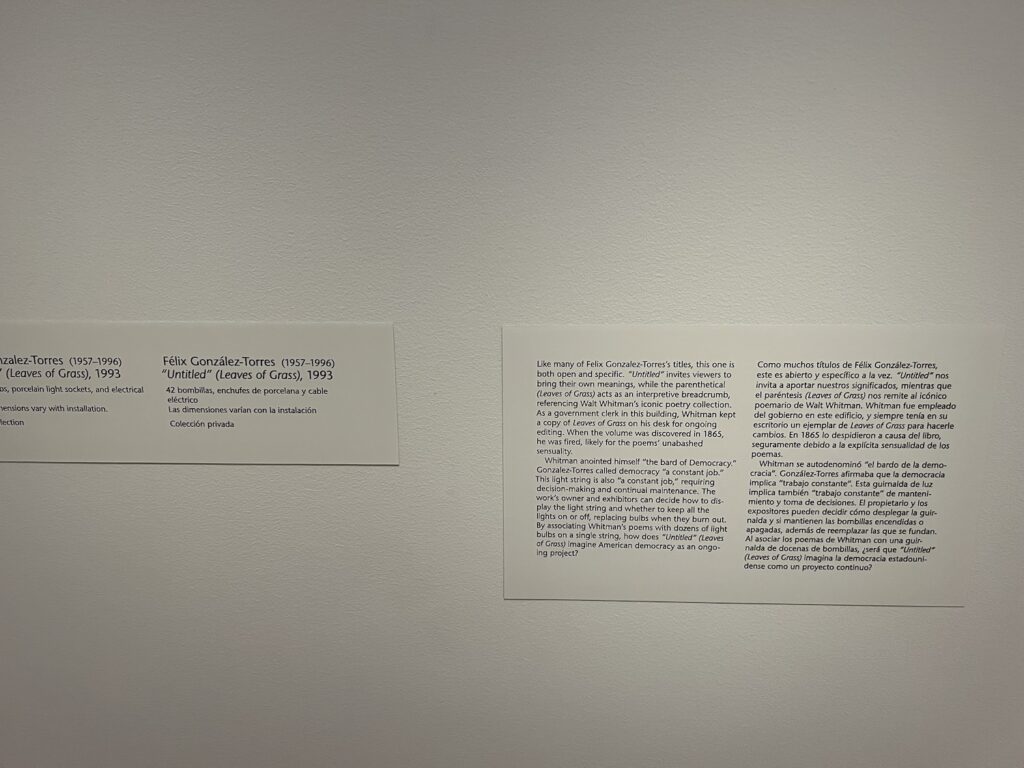

For “Untitled” (Leaves of Grass), 1993:

Like many of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ titles, this one is both open and specific. “Untitled” invites viewers to bring their own meanings, while the parenthetical (Leaves of Grass) acts as an interpretive breadcrumb, referencing Walt Whitman’s iconic poetry collection. As a government clerk in this building, Whitman kept a copy of Leaves of Grass on his desk for ongoing editing. When the volume was discovered in 1865, he was fired, likely for the poems’ unabashed sensuality.

Whitman anointed himself “the bard of Democracy.” Gonzalez-Torres called democracy “a constant job.” This light string is also ” a constant job,” requiring decision-making and continual maintenance. The work’s owner and exhibitors can decide how to display the light string and whether to keep all the lights on or off, replacing bulbs when they burn out. By associating Whitman’s poems with dozens of light bulbs on a single string, how does “Untitled” (Leaves of Grass) imagine American democracy as an ongoing project?

NGL, that did not feel like a rhetorical question today.

![wall text for National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution's portrait of walt whitman:

This intimate photograph of poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892), taken the year before his death, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres' nearby candy work, "Untitled" (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), were shown in the National Portrait Gallery's exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (2010-2011). We reunited them as a way to consider the nineteenth-century poet as a queer ancestor of the twentieth-century artist. Whitman and Gonzalez-Torres held creative strategies in common. Both continually modified their work, complicating notions of an original or static poem or artwork.

Whitman requested medicinal candy for injured soldiers when he served as a Civil War nurse IN THIS BUILDING [all caps mine. -ed.] Gonzalez-Torres cared for his partner Ross Laycock, named in the candy work's title, who died from HIV/AIDS in 1991. Captions for Gonzalez-Torres's candy works often list specific "ideal" weights. Yet as caretakers, owners, and museum staff must make ongoing decisions about the work's size and configuration, as well as whether to replenish the candy if visitors choose to take it.](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/saam-fgt-whitman-label-768x1024.jpg)

The other text, on the Eakins label:

Platinum print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

This intimate photograph of poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892), taken the year before his death, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ nearby candy work, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), were shown in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (2010-2011). We reunited them as a way to consider the nineteenth-century poet as a queer ancestor of the twentieth-century artist. Whitman and Gonzalez-Torres held creative strategies in common. Both continually modified their work, complicating notions of an original or static poem or artwork.

Whitman requested medicinal candy for injured soldiers when he served as a Civil War nurse IN THIS BUILDING [all caps mine. -ed.] Gonzalez-Torres cared for his partner Ross Laycock, named in the candy work’s title, who died from HIV/AIDS in 1991. Captions for Gonzalez-Torres’s candy works often list specific “ideal” weights. Yet as caretakers, owners, and museum staff must make ongoing decisions about the work’s size and configuration, as well as whether to replenish the candy if visitors choose to take it.

So the point was powerfully and quietly made, via a portrait of one queer ancestor by another, about the resonances between Whitman constantly reworking his poems IN THIS BUILDING [again, -ed.] and nursing for wounded soldiers IN THIS BUILDING [sigh, -ed.] and Gonzalez-Torres nursing and mourning his dying partner.

And you know, as I typed out that text, I wondered if bringing back the specific pairing from the groundbreaking queer portraiture exhibition—shamefully censored by the Smithsonian chancellor without even seeing it or consulting the curator or museum leaders—and calling Whitman the queer ancestor, are curatorial workarounds for a Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation or Estate demand that his gay identity not be mentioned. Because that would be slick, and would also be worth reporting on, and calling out.

In 2007, after decades of community lobbying, a public art tribute was made to the volunteers and caregivers of people living with and dying from HIV/AIDS. An excerpt from the end of Walt Whitman’s poem, The Wound-Dresser was engraved around the entrance to the Dupont Circle metro station, the longtime heart of Washington, DC’s gay community, and three stops from the National Portrait Gallery:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night – some are so young;

Some suffer so much – I recall the experience sweet and sad . . .

The last two lines of the poem,

(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have cross’d and rested,

Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)

were left off. But they happened—and were edited—in the building.

Previously, related: Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ MLK