So “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), 1991, is unique, but it is not the only one. Now that it has sold “a serious hold” and a $US16m asking price, let’s take a look at the six [!] related works Felix Gonzalez-Torres made. And then decided were not works after all. What are they, where are they, and what is to be done with them?

Tag: felix gonzalez-torres

All In A Day’s Work

Hauser & Wirth showing Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform) at Art Basel Unlimited this week. Seeing a video on H&W’s insta of the dancer hopping off the platform and heading out of the halle, accompanied, like a Disneyland character, by a handler, reminds me of artist Pierre Bal-Blanc’s 1992 video work, Employment Contract.

Bal-Blanc was a go-go dancer for the 1992 installation of Felix’s work at the Kunstverein Hamburg, for a show called “Ethics and Aesthetics in times of AIDS.” Employment Contract is a wordless slice of Bal-Blanc’s life that happens to have a brief go-go dancing stint in the middle of it.

One of the tenets of “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), reaffirmed just a couple of weeks ago when the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation published an in-process version of core tenets for the work, is that the dancer’s schedule is their own, and it is undisclosed. The dancer chooses whether to share their schedule with the exhibitor, and the exhibitor is to take care not to disclose it, and to provide adequate accomodations for the dancer to go about their business. From the viewing, and even the exhibiting standpoint, this work of Felix’s entails a high degree of uncertainty, and a very low probability at any one moment of there being a dancer dancing.

Bal-Blanc turns this sense of expectation entirely inside out. The video camera tracking him as he jogs through the streets of Hamburg gives no hint at all of what is to come; he’s just a guy, jogging, in jorts. The surreal absurdity of him walking into a museum, unlocking a supply closet, stripping down [to silver and black briefs, a kludgey two-tone outfit that would not pass muster with the Core Tenets crowd], and grooving in an empty gallery for several minutes, defies narrative logic. And yet he goes right on with it, and back out of the museum. All in a day’s work.

This question of context and expectation is one of the perennial sources of power for Felix’s work, especially this one. Encountering a go-go dancer in a museum might feel as disorienting as a pile of candy you can eat from. More than 30 years on, Hauser & Wirth’s instagram comments are somehow still full of people still confused or contemptuous of this work as art. And while art world folks have certainly consumed and processed Felix’s work fully, seeing this piece, from this gallery, at an art fair, the least wild thing about it is the dancer.

[next day update]: indeed, it looks like the Core Tenets got updated just in time, because the work that had been on “permanent loan” to the Museum St. Gallen is for sale by the Swiss collectors who’ve owned it all along. Donald Judd would not be surprised. It does make me want to take a new look at the five go-dancing platforms and lighted pedestals listed in the “non-works” section of the CR.

On The Materialization Of The Art Work

“If an owner has chosen to lend the work for an exhibition, the owner may choose to simultaneously install the work.”

“An authorized manifestation of [the work] is the work, and should be referred to only as the work.”

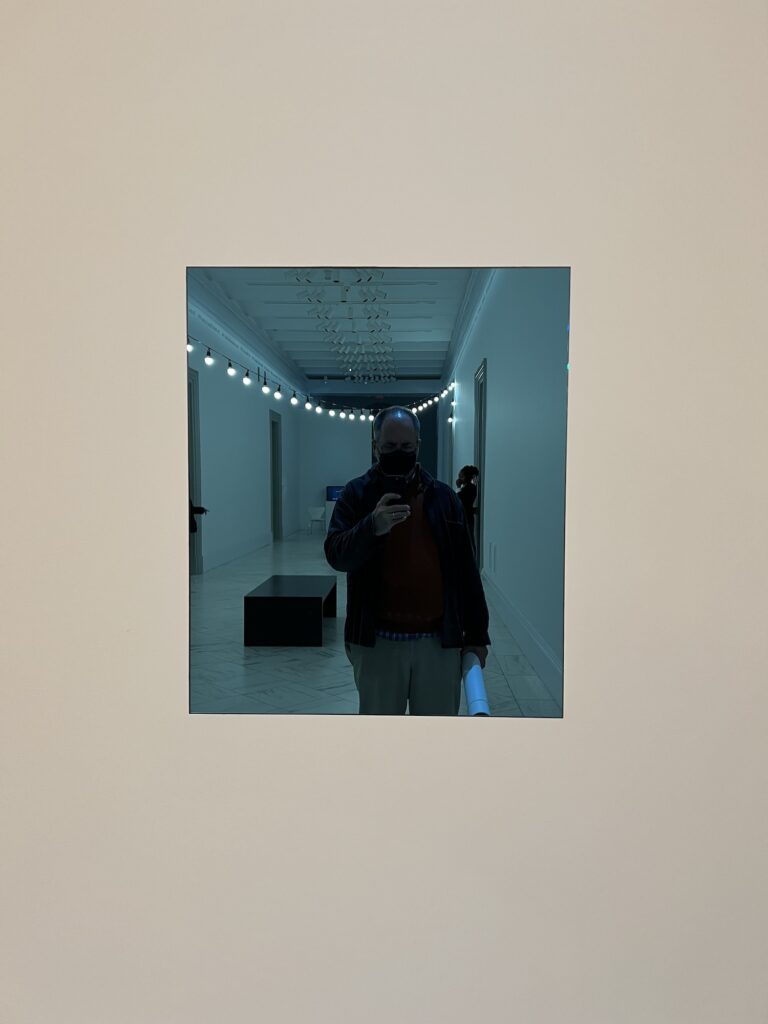

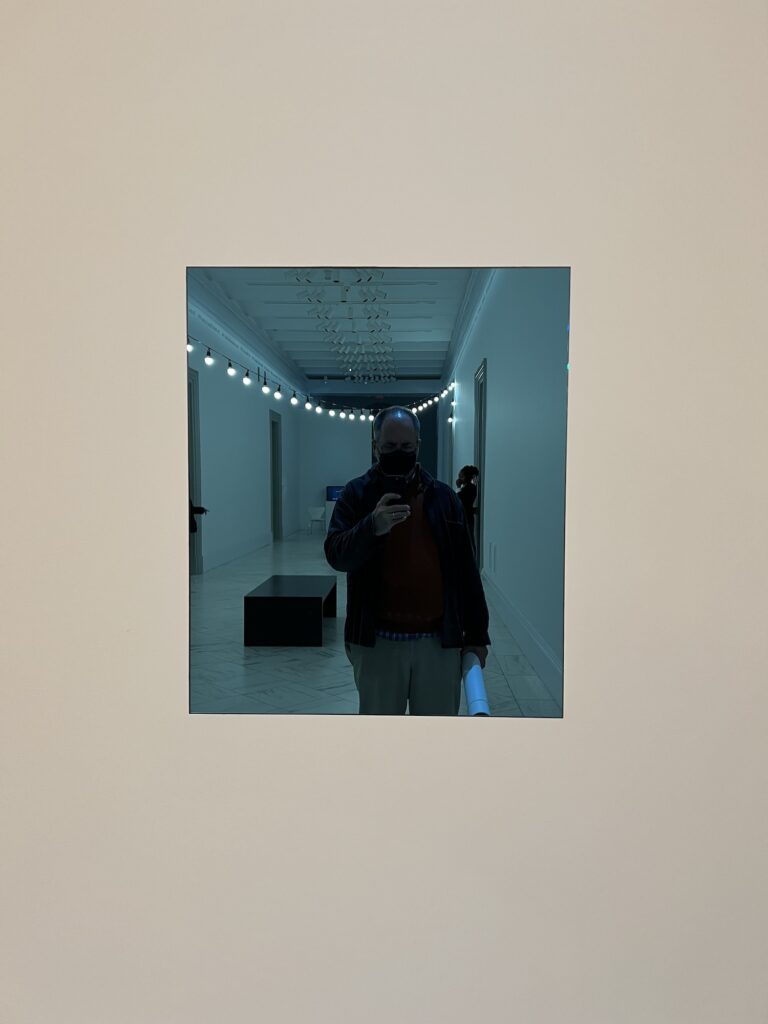

Via a recent post to Instagram by the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation I learned what I could have realized many years ago: that “Untitled” (Fear), 1991, the blue-tinted mirror, is not an object, but a work. And as such, it can be presented in multiple manifestations simultaneously.

In fact, it has, and it is.

Continue reading “On The Materialization Of The Art Work”RTFM: FG-T @NPG/AAA BTS

There is a book. I did not know there is a book. I’ve visited the Felix Gonzalez-Torres show at the National Portrait Gallery & Archives of American Art multiple times and have written about it even more, and I did not know there was a book. I fixated on Felix’s “Untitled” text portrait in both its installed versions, and wondered how the Smithsonian’s curators made them, and I picked through the history of this and other text portraits, and wrote a whole-ass blog post about it, and I didn’t know there was a book.

Reader, there is a book, and it is literally about all of that. In Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Final Revenge (A Workbook), co-curators Josh T. Franco and Charlotte Ickes wrote a whole essay on their experience and process of creating the versions of “Untitled” they’ve showed. Along the way, they fill out many key aspects of Felix’s work, from its changing history to its changing present.

Continue reading “RTFM: FG-T @NPG/AAA BTS”I’m Not Afraid Of Correcting Mistakes

Maybe it’s the passage of time, the advancement of discourse, the writing and thinking about it for so long, the engagement with the work and history of an artist who wrote so emphatically, that he’d always believed artists were allowed “to do whatever they please with their work.” Or maybe it’s the moment, when something I’ve seen and written about before looks different. And when something I’ve read a dozen times before finally sinks in, maybe because now I’ve had that same experience.

“I’m not afraid of making mistakes, I’m afraid of keeping them,” Felix Gonzalez Torres told Tim Rollins in 1993.

Andrea Rosen put that quote in context in her CR essay [pdf], and how Felix’s decision to not have a studio meant the first time he’d see a work realized was when he installed it in a gallery: “Putting the work in public immediately allowed him the opportunity to sense if he felt confident about his decisions. From time to time Felix would decide that he did not feel strongly enough about a piece to have it remain a work, even if it had already been exhibited.”

Continue reading “I’m Not Afraid Of Correcting Mistakes”“Untitled” (The Neverending Self-Portrait)

We were in the neighborhood, and so we went back to see the Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Which was the first time we spent time with “Untitled” (1989), a portrait work which appears twice, in two different configurations, in two different spots of the exhibition. [Technically, it’s in three spots: the work is owned by the Art Institute of Chicago, where it’s been on view since December 2023.]

In the show it felt impossible to do more than sense the differences between the two installations. It seemed that, in the absence of a subject named in parentheses, this was a portrait of the artist himself, but the variety of posthumous additions made it non-obvious. So we left with questions: How was this portrait adapted for this dual/triple version? Besides the title, how [else] was it different from the others? If it was indeed a self-portrait, how did this portrait practice come to be?

Helpfully, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation collects documentation of each version as it is installed. As the first portrait [sic] that was, indeed, a self-portrait, which was in Andrea Rosen’s collection [The AIC got it in 2002], “Untitled” (1989) may be one of the most frequently exhibited; the documentation for [at least] 42 versions runs to 17 pages [pdf].

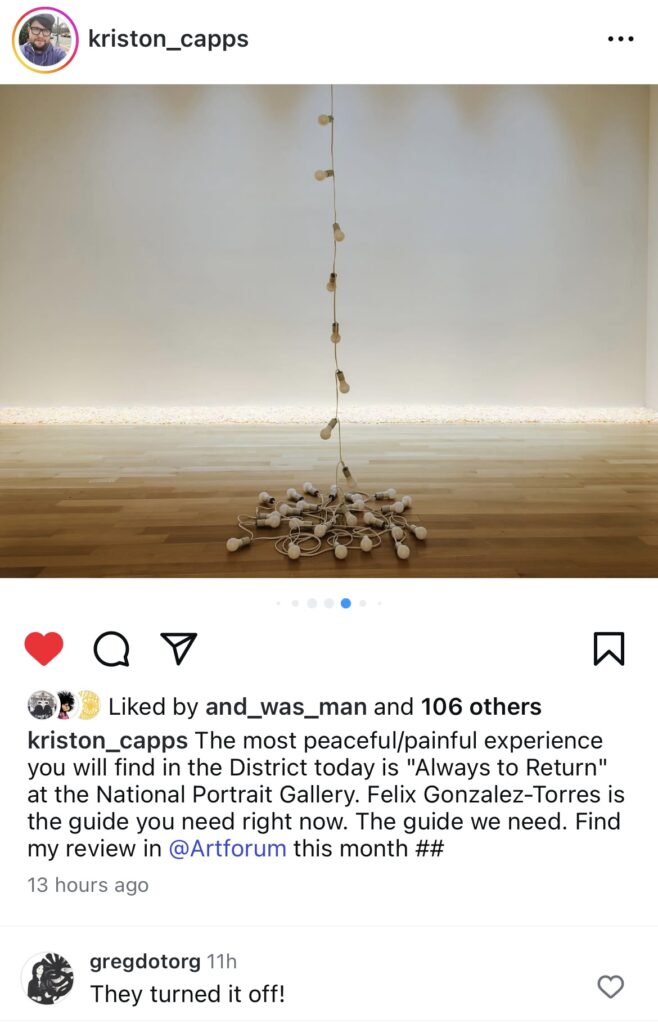

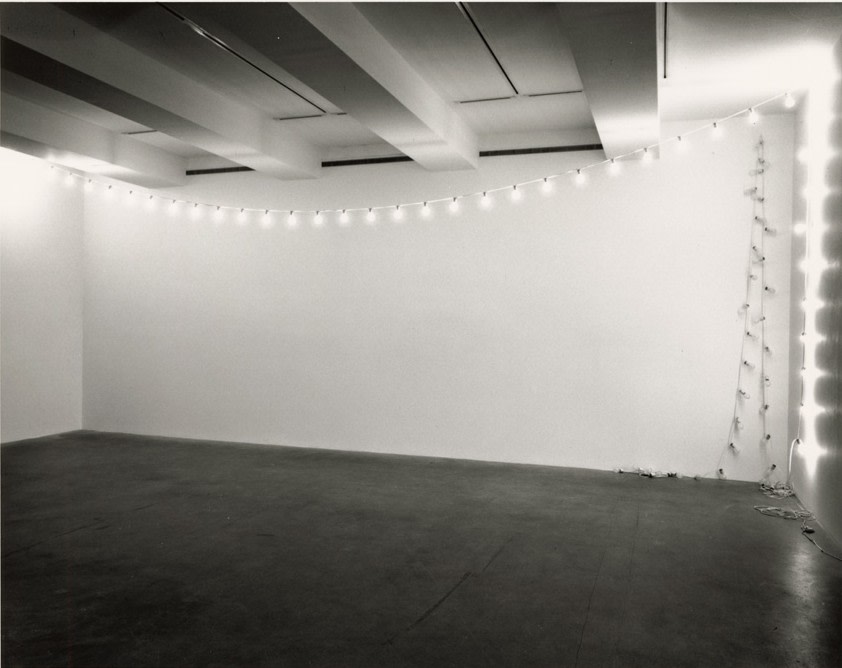

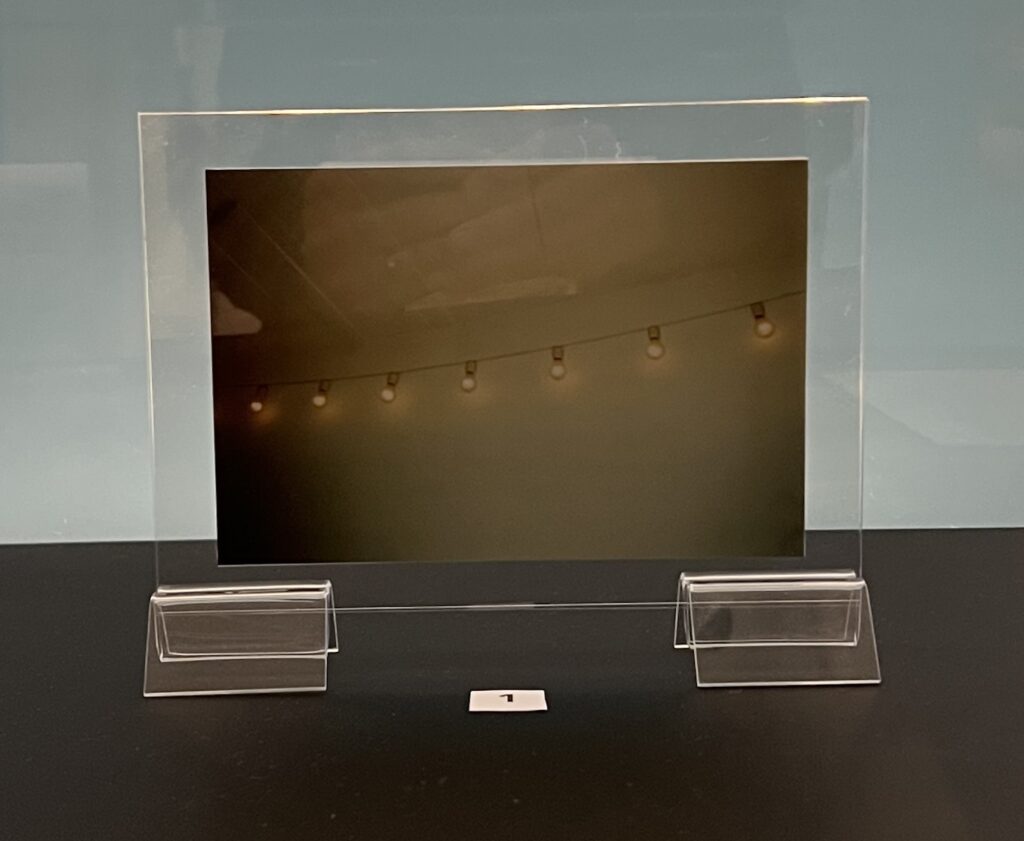

Continue reading ““Untitled” (The Neverending Self-Portrait)”The Light String Going On And Off

As my comment on Kriston Capps’ insta shows, it’s somehow always a surprise to see a Felix Gonzalez-Torres light string with the lights off. My reaction led Kriston to doublecheck with the National Portrait Gallery whether it’d been OK to post [tl;dr it was, but hold on], and it sent me looking for more.

Of course, it goes back to the beginning, where they were shown on and off, side by side. Gonzalez-Torres’ whole point of his works was that the owner [or exhibitor] was to decide how to display them, and that includes whether to turn them on. The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation has photos of an unlit “Untitled” (Tim Hotel), 1992, in a collector’s home, which feels like the normal, private state. Maybe it gets turned on for company, which raises the question of public vs. private presentation as well as space.

Because obviously, they look the sexiest when they’re on, and it’s understandable for curators of public exhibitions to want that glow. But that allure also underscores the impact and importance of seeing them turned off sometimes.

Continue reading “The Light String Going On And Off”“Double Fear” For The Bidding Crowd

On June 16, 2021, Pablo Martinez, the head of programming at MACBA, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, gave a talk about Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ use of the motif of crowds in his work. In a socially distanced auditorium still wary of crowds and the threat of viral contagion they posed, Martinez presented key early works by Gonzalez-Torres where crowds alluded to the protests and epidemic fears of the AIDS crisis. With callbacks to Baudelaire, Benjamin and Barthes, crowds also embodied the dualities of community and alienation, catalyzing liberation and identity as often as they dissolved the self into anonymity.

Martinez spoke as part of “The Performance of Politics,” a one-day conference on Felix’s approach to identity politics: “Felix Gonzalez-Torres deliberately sought to stand outside any identity essentialism and, on the contrary, to activate various strategies of disidentification, as José Esteban Muñoz put it, in response to the state apparatuses that employ racial, sexual and national subjugation systems through protocols of violence and exclusion.” [All the talks are available on YouTube, which is pronounced youtubae in Spanish.] Which was part of an exhibition, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: The Politics of Relation,” curated by Tanya Barson, that examined the artist’s work in the context of the Latin world.

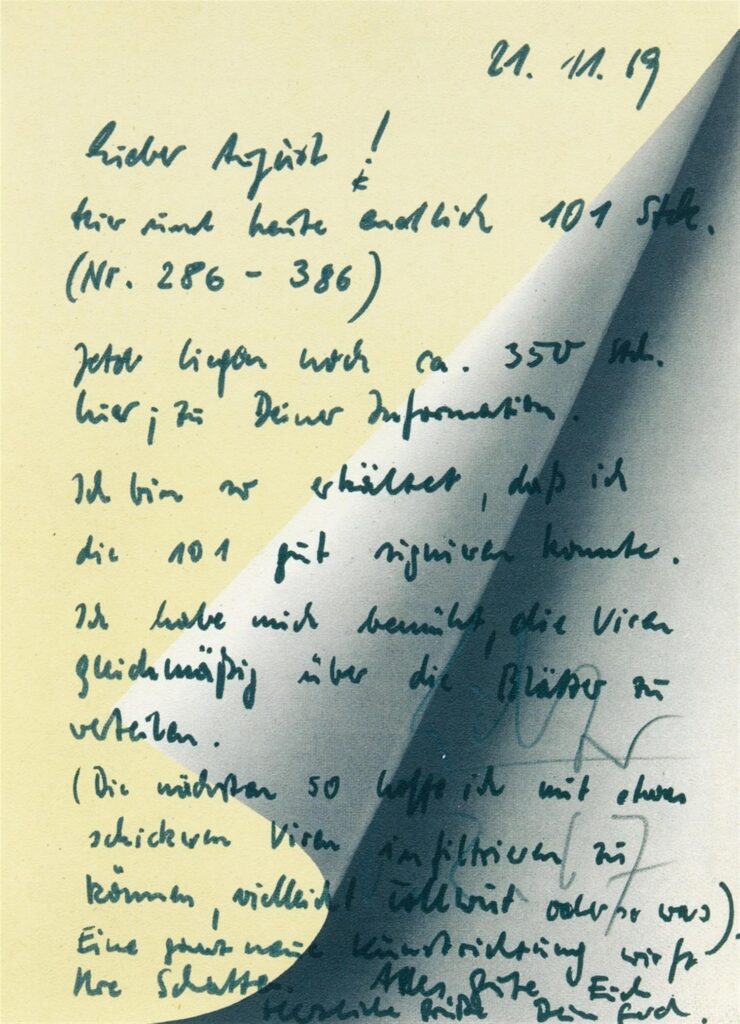

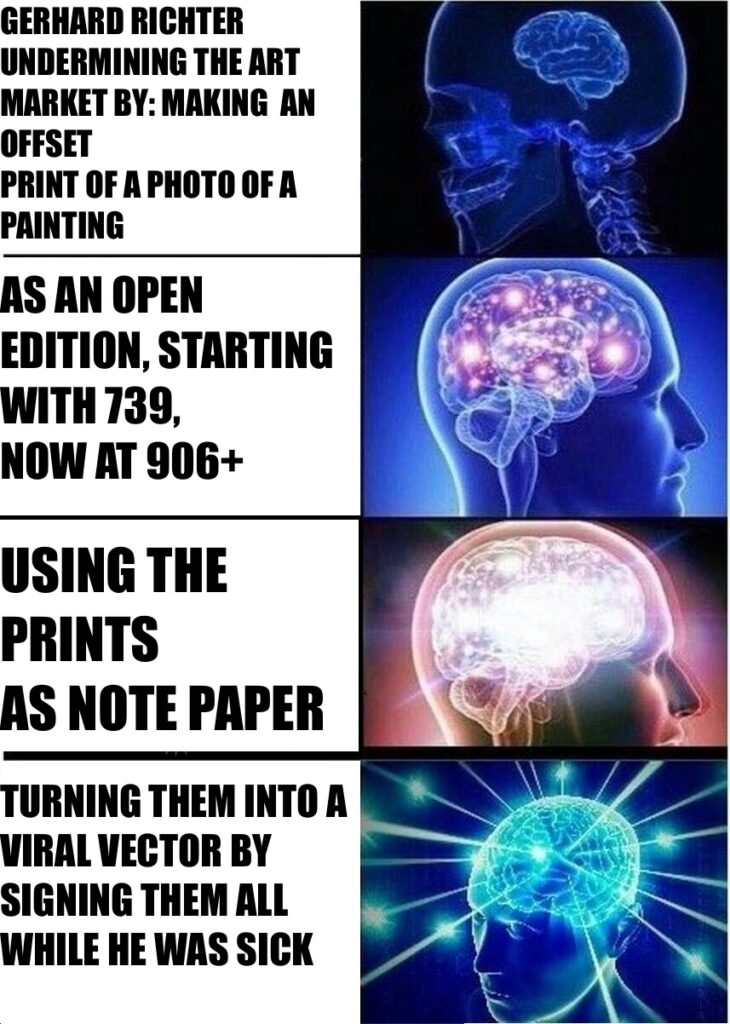

Gerhard Richter, Viral Artist

And here I thought that Gerhard Richter’s critique of the art market by making an offset print in an open edition was surpassed only by his using the prints as note paper. Claudio Santambrogio is much better than I at deciphering Richter’s handwriting, and he figured out the entire note Richter wrote to his dealer August Haseke in November 1969 when he finally delivered the first half of his 1967 open edition, Blattecke. And it is a whole new art direction casting its shadow:

Lieber August,

Hier sind heute endlich 101 Stück (Nr 286-386).

Jetzt liegen noch ca. 350 Stück hier; zu Deiner Information.

Ich bin so erkältet, dass ich die 101 Stück gut signieren konnte. Ich

habe mich bemüht, die Viren gleichmäßig über die Blätter zu verteilen.

(Die nächsten 50 hoffe ich mit etwas schickeren Viren infiltrieren zu

können, vielleicht Tollwut oder so was).

Eine ganz neue Kunstrichtung wirft ihre Schatten.

Alle gute Euch

herzliche Grüße

Dein Gerhard

Dear August,

Here are finally 101 pieces today (nos. 286-386).

Now there are still about 350 pieces here; for your information.

I have such a cold, I could sign 101 pieces. I have tried to

distribute the viruses evenly over the sheets.

(I hope to infiltrate the next 50 with some fancier viruses, maybe rabies

or something).

A whole new art direction is casting its shadow.

All the best to you

best regards

Your Gerhard

This is not what I envisioned when I mentioned a Felix-like stack, and yet the shadow is cast.

[week later update: these notes and additional related material are now in the Richter Archive in Dresden. Apparently it took Richter three years to work his way through signing the first 739 Blattecke.]

Previously, related: There Are At Least 906 Blattecke

Stack(Ed.)

When Form Becomes Content, or Luanda: Encyclopedic City, On The Stack as Medium

In The Building

Well that took five minutes.

The erasure or diminishment or downplaying or whatever of the gay, AIDS, and immigrant identity of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and those identity characteristics as vital context and reference in which he made his work in the 1980s and 1990s, is real and should be called out and resisted. It happened publicly and messily at the Art Institute. It happened similarly at Zwirner. It happened in subtle, coercive ways art historians and critics called “oppressive.” But addressing it’s not a question of either/or, but of both/and, as Johanna Fateman skeeted, and expanding the meaning of the work, the contexts in which it resonates, and the changes in the world around it every time it’s exhibited should build on the artist’s achievement in its original moment, not replace it.

Anyway, this debate is not advanced by the current outcry over the show at the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always To Return, because the claimed erasure is not happening. I’m not going to litigate Ignacio Darnaude’s impassioned but wrongheaded, blinkered, and inaccurate article condemning the way “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), a 1991 candy pour is presented. Its connection to AIDS is not erased. Felix’s connection to Ross is not erased. And as I walked out of the Felix galleries, past the James Baldwin and The Voices of Queer Resistance exhibition next door, and on through the permanent collection install, I have to say, there is no museum anywhere doing more of the work right now than the NPG & SAAM.

So. Here is the way “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is presented.

Continue reading “In The Building”Specific Objections About Specific Identities

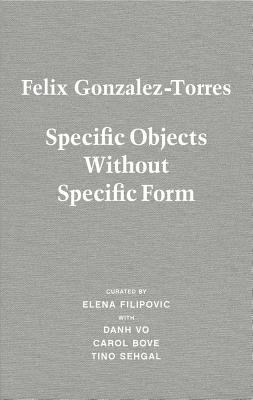

Specific Objects Without Specific Form, the 2010-2011 retrospective of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work, curated by Elena Filipovic, was a pivotal influence in the posthumous reconsideration of the artist’s work and legacy. It was co-curated with three artists, Danh Vo, Carol Bove, and Tino Sehgal, in three European museums: WIELS (Brussels), the Fondation Beyeler (Basel), and MMK Frankfurt.

Frequent changes and reinstallations were the default, and each artist brought entirely different concepts for reimagining the work and its history. I would be surprised if a hundred people on earth saw every iteration and variation over the show’s 15-month run, and so the massive catalogue, published in 2016, is the primary vehicle for transmitting the experiments and experience of the exhibition.

The core of the catalogue, at least as it relates to the recontextualization of Gonzalez-Torres’ work, is a 20+ page conversation between Tino Sehgal and dealer Andrea Rosen. Rosen is the single most influential figure in the history of FG-T’s work, and the single biggest reason it’s been preserved, shown, and studied during his life, and after his death. I don’t know of any more extensive discussion of Rosen’s views on Gonzalez-Torres’ work, and the core of her message here is that it is about change.

Though there are some persistent, static objects in Gonzalez-Torres’ body of work, the most significant ones are all recreated every time they’re shown. It is the discussion and decisions that occur around each of these realizations that constitute the history of the work. Those changes, and marking them, and questioning them, and questioning the context a work is presented in each time it is realized, are, Rosen argues, central to Gonzalez-Torres’ original intention for his work.

“He would always say,” Rosen quoted Felix as saying, “‘If someone chooses to never install a work again, or manifest a manifestable work again, it may not physically exist, but it does exist, because it did exist.'” Some of his works have recently been manifest at the National Portrait Gallery, and the changes and decisions around them have prompted criticism. This has happened before, with these same works, with the same institution, even, and with some of the same people—including Rosen—stewarding Gonzalez-Torres’ work. The most public shift and criticism has been specific objections about specific identities: the seeming erasure or diminishment of the artist’s identity as a gay man, a person with AIDS, and a Cuban-American, as generative to his work. It got attention after Rosen brought David Zwirner in to co-represent the artist’s estate. But, as this show, and this book, and this interview, document it’s been underway for much longer.

I’m going to take another look at these contested works, and reread the Rosen/Sehgal interview, and report back. brb

Previously, related: Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

A 2010 visit to Hide/Seek: ‘It Gets Better’ doesn’t mean the bullying stops

Felix Navidad Post Office

to return, National Portrait Gallery

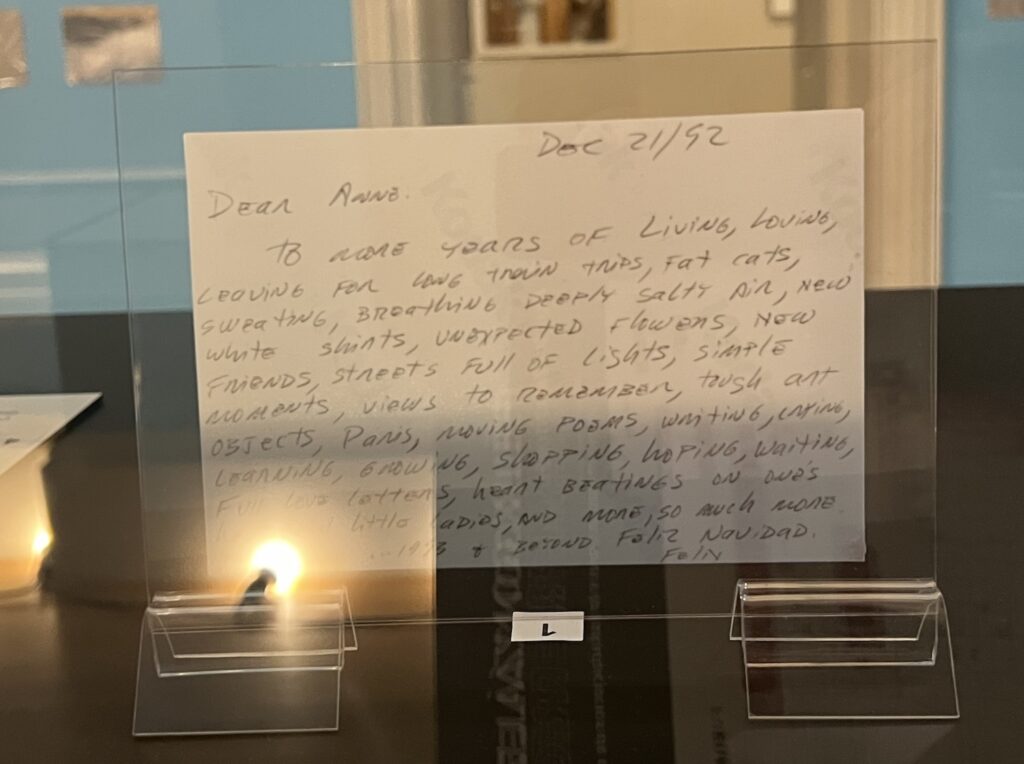

I had wanted to post this snapshot Christmas card Felix Gonzalez-Torres sent to MoMA curator Anne Umland again on the date he wrote on the card, December 21, but I missed it. So I am posting it on the day I imagine he posted it.

Previously, related: Felix Navidad Exhibition Copy

Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

Felix Navidad Exhibition Copy

One unexpected thing from the Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery is the inclusion of a few examples of the artist’s correspondence, the notes and snapshots he regularly sent to friends and colleagues. They’re shown amidst all 55 of the artist’s photo puzzles, which underscores their similarity to the photos and letters Felix used. But only to an extent. By expanding the borders of the pool of imagery and text from which the artworks were drawn, they reveal nuances of the artist’s decisions.

And when it’s correspondence with curators and collaborators, they trace the network of relationships in which Gonzalez-Torres worked and lived. One example is two similar Christmas cards sent to Julie Ault and MoMA’s Anne Umland in 1992. Umland’s lightstring snapshot might be the OG Felix Navidad.

The text reads: “Dear Anne, To more years of living, loving, leaving for long train trips, fat cats, sweaters, breathing deeply salty air, new white shirts, unexpected flowers, new friends, streets full of lights, simple moments, views to remember, tough art objects, Paris, moving poems, writing, crying, learning, growing, shopping, hoping, waiting for love letters, heart beatings on one’s [?], little radios, and more, so much more, …in 1993 and beyond, Feliz Navidad, Felix”

One thing I can’t figure out, though: according to the checklist, this is an exhibition copy, on loan from MoMA. Did the museum decide not to loan a piece of correspondence from their archive? Or did Umland keep the personal card, but give the museum a facsimile? What goes into producing a double-sided photo & handwritten text? Because I feel some new facsimile objects coming on.

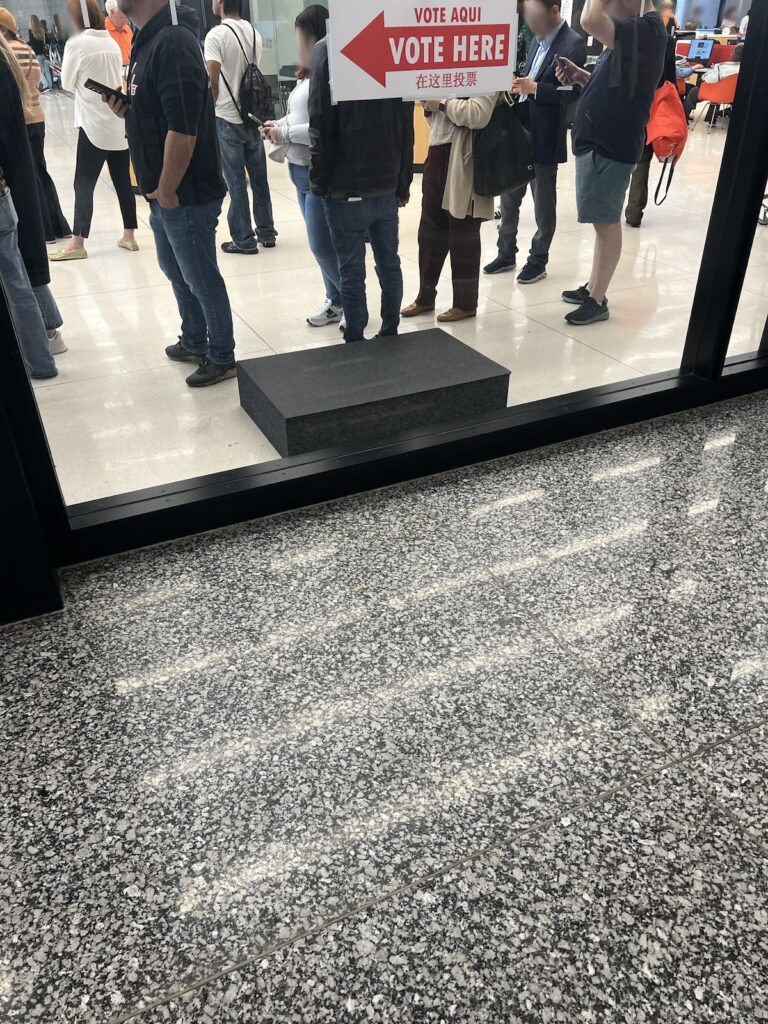

Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ MLK

It’s also installed at the National Portrait Gallery, but after seeing the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation’s instagram, I realized I had missed this 1991 stack, “Untitled” (Party Platform 1980-1992), at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. So I went back to see it, and the place was full of people voting.

Oddly, it does not get out much.

Previously: Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

Felix Gonzalez-Torres @ NPG

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, at and around the National Portrait Gallery is excellent in several precise and unexpected ways:

The inclusion of all 55 of the artist’s puzzle works [first shown like this at Art Basel 2019, including with five exhibition copies, which I didn’t know was a thing here.]

The inclusion of strong non-signature works like “Untitled” (Fear), above, and “Untitled” (A Portrait), the artist’s only video work.

The inclusion of two variants of the portrait [sic] of flowers on Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas’ grave. [n.b.: There are more.]

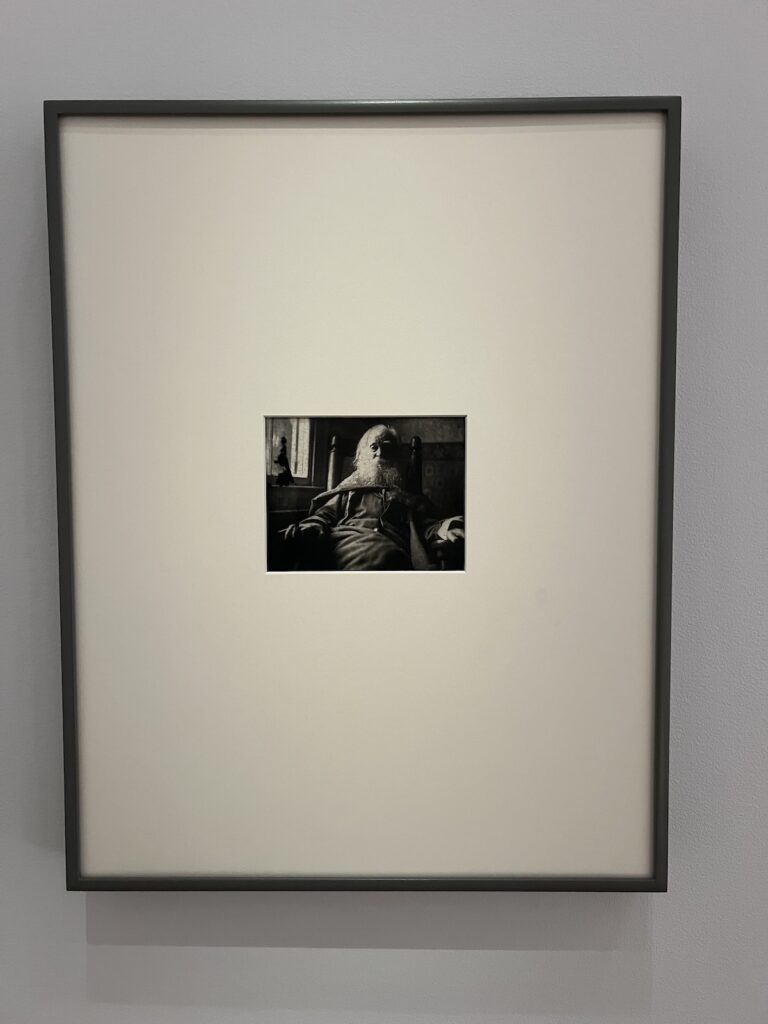

But the most intriguing and effective thing was the threading of Felix’s work throughout and among the collection of the NPG. It worked in small, even tiny ways, like reuniting a little Eakins portrait of an ancient Walt Whitman with a candy pour, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), which had been shown together at the NPG’s 2010 Hide/Seek exhibition of queer portraiture.

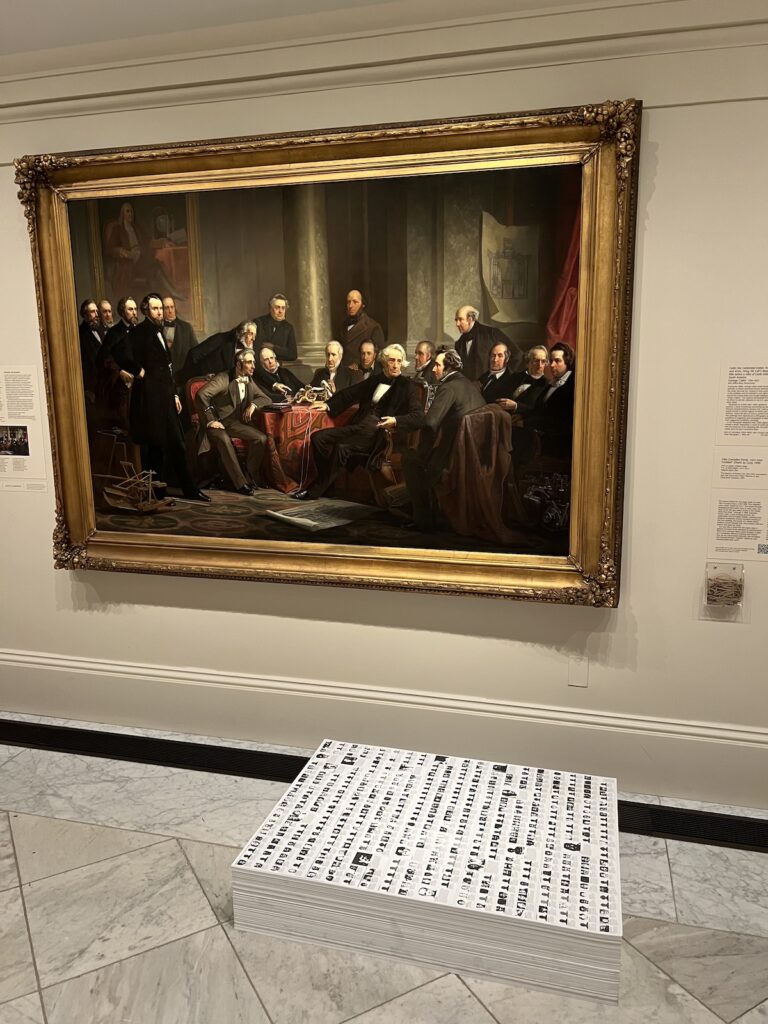

But it hit hardest and most unexpectedly in the most intrusive installation: “Untitled” (Death by Gun), the stack of photos of Americans killed in one week of gun violence, on the floor of a heavily trafficked hall gallery, in front of two works that felt like the NPG’s 19th century bread and butter.

The painting turns out to be Christian Schussele’s 1862 Men of Progress, an amalgamated portrait of various American inventors, including Samuel Colt, inventor of the revolver pistol that made shooting people easier, quicker, and more convenient.

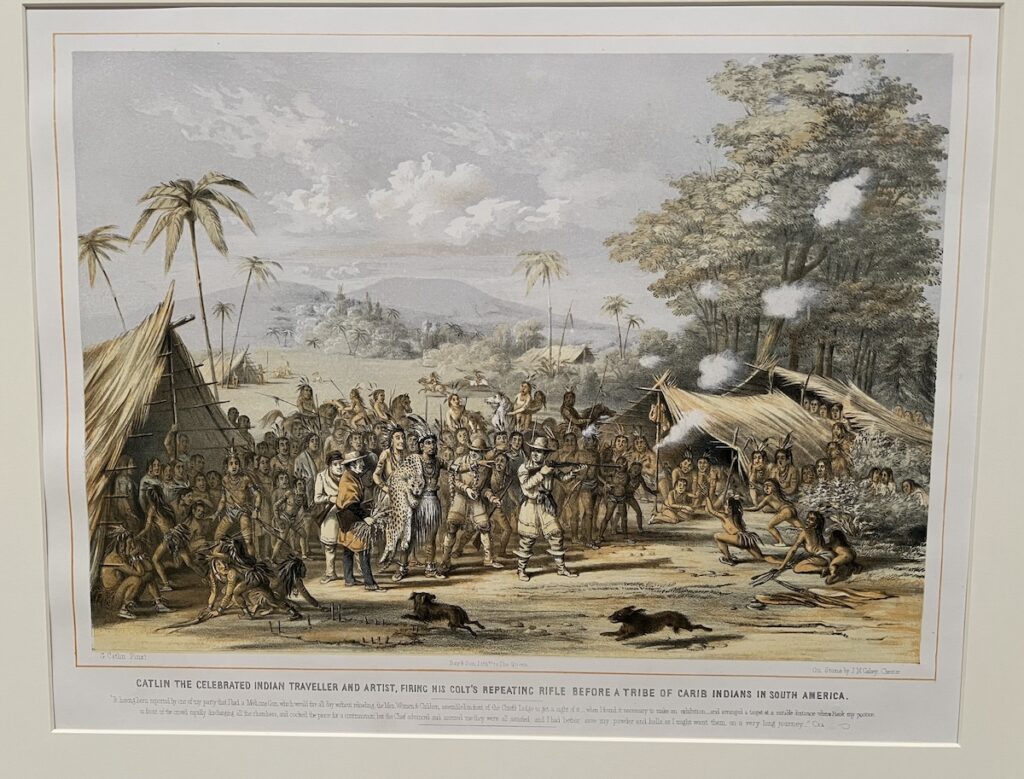

Next to them [in a way I could have photographed all three together, had I only realized the complexity of the connection] is a print after a George Catlin painting, where the artist shows off a Colt rifle to a group of Carib Indians. Turns out that after the economic failure of his massive “Indian Gallery” project, Catlin accepted a commission for a series of paintings for an aggressive marketing campaign promoting Colt’s new guns. That went well. For the gunmakers, at least.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return runs through June 2025 or until the end of the republic, whichever comes first [npg]

Previously, related: on Hide/Seek and the controversies around its censorship