Maybe it’s the passage of time, the advancement of discourse, the writing and thinking about it for so long, the engagement with the work and history of an artist who wrote so emphatically, that he’d always believed artists were allowed “to do whatever they please with their work.” Or maybe it’s the moment, when something I’ve seen and written about before looks different. And when something I’ve read a dozen times before finally sinks in, maybe because now I’ve had that same experience.

“I’m not afraid of making mistakes, I’m afraid of keeping them,” Felix Gonzalez Torres told Tim Rollins in 1993.

Andrea Rosen put that quote in context in her CR essay [pdf], and how Felix’s decision to not have a studio meant the first time he’d see a work realized was when he installed it in a gallery: “Putting the work in public immediately allowed him the opportunity to sense if he felt confident about his decisions. From time to time Felix would decide that he did not feel strongly enough about a piece to have it remain a work, even if it had already been exhibited.”

For so long, I’d felt that historical fact—that a work had been exhibited and presented as an artwork, even given or sold as one—was at odds with Felix’s decisions to create what felt like entire bodies of non-work. These objects, these things, these non-work works, still have a place in the history and context of Felix’s practice. But with Andrea’s quote, it hit me how differently this exhibited-or-not criterion functioned for Felix. Maybe some artist would see a piece for the first time installing it, and decide it didn’t work, and not show it. And maybe that happened to Felix, too. But this is the idea of being OK to sit with a piece in public and then reject it. And Felix was fine with that.

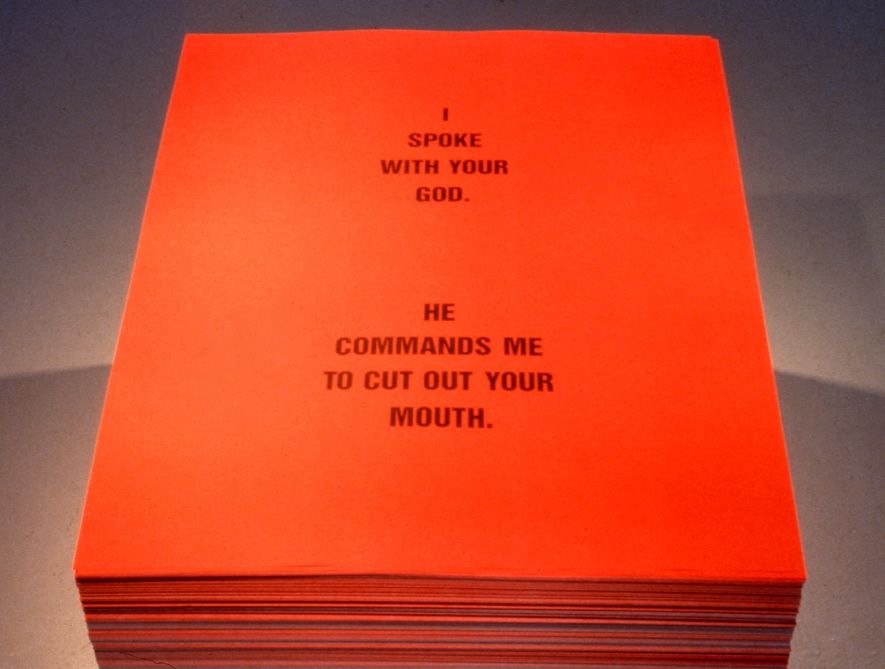

This realization happened while looking at the 1990 show in Vancouver where Felix showed an atypically large version of his 1989 text self-portrait, “Untitled” [as Untitled (Still Life)], across from Donald Moffett’s graphic lightboxes. In the middle was a joint work, “Untitled” (I Spoke With Your God), a paper stack with sheets designed by Moffett. How could a whole-ass paper stack become a non-work, I wondered? Especially when other stack collabs, with Michael Jenkins and Louise Lawler, are right there? [It did not help that I was wondering this while the Foundation was revising their own documentation practices and updating their website, and it looked like entire sections of the CR were being buried. Which, fortunately, is not what happened. But still.]

Anyway, seeing this stack again, I realized that thinking of it only in terms of its implications for Felix’s work missed a major point. Because it was a joint work, a work by Donald Moffett. And maybe Felix felt it was more Moffett’s work than his.

And maybe it still is. Before and after their show, Moffett was making a weekly artwork-as-agitprop series called, Age of AIDS, which was published in the Village Voice from 1989 into 1992. It included some of Moffett’s most iconic artworks from that moment, and I think the Vancouver lightboxes were from the series, too.

While searching for the origins of the poster’s text, basically every reference to it was to Moffett. In March 1990, eight months before Vancouver, Moffett showed assembled groups of lightboxes, one-per-word, at his New York gallery, Wessel O’Connor. According to this Outweek review [pdf], I Spoke To Your God. He Commands Me To Cut Out Your Mouth was among them. This was months after Christian extremists and right-wing politicians bullied the Corcoran Gallery into canceling a Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective—and at the exact moment when more Christianists stormed the show at the CAC in Cincinnati, getting its director arrested for obscenity. So some hateful people were indeed claiming to speak for God.

When the Vancouver show opened in November, Moffett’s lightbox I Spoke To Your God… was on view again, in Atlanta, in a gay art-related group show at the TULA Art Center.

And though I can’t find pictures of it, Julie Ault included I Spoke To Your God… in Power Up: Reassembled Speech, Interlocking, a show of Moffett and Sister Corita Kent, which started at The Wadsworth Athenaeum in 1997, and went to the Hammer Museum in 2000.

So we’ve heard from God and Felix; maybe it’s time to see what Don has to say.

Non-work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in collaboration with Donald Moffett [fg-t fndn]

Previously, related: Soft-Core: On Additional Material and Non-Work

Untitled (Additional Material), 2021