[THERE’S AN UPDATE: READ ON, THINGS ARE BETTER THAN I WOUND MYSELF UP TO THINKING.]

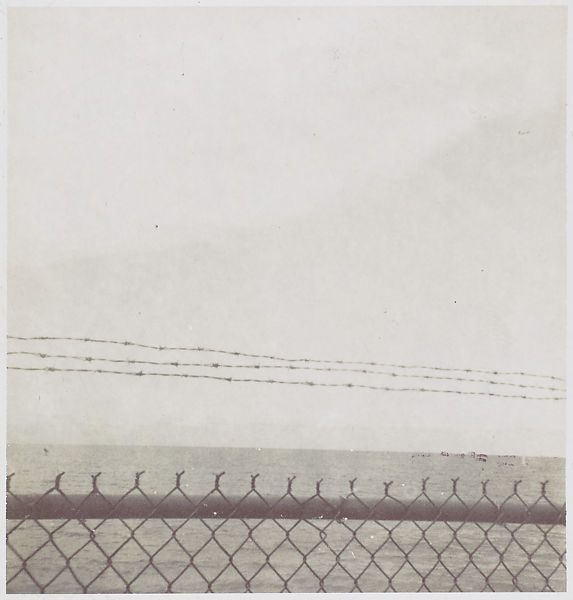

The earliest work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection is also the smallest. It is untitled, an instant black & white photo of the sea through a Cuban fence. It’s about 2.75 inches square. It is signed and dated 1985, and has a fragment of a magazine collaged on the back that reads, “THE BO–/ ANYMORE.” By the time it was acquired at the end of 1996, the year of the artist’s death, the Met had already acquired two similar sets of photos by Gonzalez-Torres: photogravures of sand, and cloudscapes. Similar, but different: this one is not an artwork. “Although made, signed, and dated by the photographer,” the catalogue entry reads, “Gonzalez-Torres thought of works such as this [photo] as lying outside his core oeuvre.”

Published in 1997, just in time to record the Met’s acquisition, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Catalogue Raisonée has three categories: Works, Additional Material, and Registered Non-Works. The photo above is in the second category. When the CR was released, Gonzalez-Torres was the most important artist in the world to me, and I wanted more of his works, not fewer. I was upset for these somehow downgraded works, and for the sleights they faced in the discourse, the gallery, the market. I couldn’t accept that the same artist who’d shown me that the most remarkable things could be art–a pile of candy, a stack of paper, a jigsaw puzzle, a pair of clocks–also said they couldn’t be.

My incredulity over Felix’s work fueled a years-long contest with the declarative process, what artists called objects, what they kept, what they destroyed. It helped me keep an eye out for these marginalized–and invisible, since there weren’t even any pictures–works. But even as I developed more nuanced appreciations of [other] artists’ agency, these non-art designations still gnawed at me. Until the other night, when I started writing this. It’s been almost 25 years: what’s going on?

The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Catalogue Raisonée began as an exhibition catalogue for the artist’s first museum shows in Germany [at the Sprengel Museum, Hannover] and Switzerland [at the Kunstverein St. Gallen.] When Felix died in January 1996, after his Guggenheim retrospective, and 18 months before the opening in Hannover, Sprengel curator Dr. Dietmar Elger and gallerist/executrix/estate Andrea Rosen opted to make the catalogue a CR. Which is an almost unheard of timeframe for pulling a CR together, but also a devastating and emotionally fraught moment, too.

Elger’s preface considers the various ways a CR can be constructed, from excluding everything but authorized, so-called “signature” works, to documenting every napkin doodle. This phrase, a “core oeuvre,” is from Elger. [Elger would go on to edit Gerhard Richter’s CR, which the artist actively works on as a conceptual work and narrative in itself. For compleatness, Elger also runs Richter’s own repository for Everything Else, the Richter Archiv in Dresden.]

Gonzalez-Torres’ “core oeuvre” comprises just 281 works, dating from 1986 to 1995. [The FG-T Foundation lists 284, but that’ll come later]. Additional Material included many gifts or traded works, and the art he made in 1980-83 while getting his BFA at Pratt. 54 works (sic), a total of 63 objects, including three with multiple examples. Almost half, 21, relate to 29 core artworks. Some are extra examples of an edition. Some are single sheets from a stack or single images from a set. There are variations of size, cropping, or biographical text. Elger notes that the artist explicitly instructed that his student-era work and two larger versions of existing, early works, “not be considered a work.”

33 Registered Non-Works include exhibition copies and objects from early in the artist’s life in New York: variations or additional examples of seven existing works; five go-go dancing pedestals [presumably destroyed]; three stacks; two pours; a billboard; an engraved belt buckle (in an edition of three); and the artist’s commissioned installation for the Public Art Fund. “These are works,” Elger wrote, “which have been shown in exhibitions, published in the literature and listed in the inventory book but were later no longer acknowledged by the artist as constituting art and hence stricken –by him–from the oeuvre.”

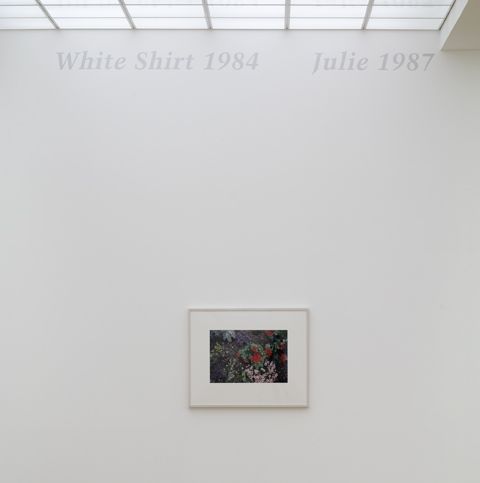

Some examples: Gonzalez-Torres gave versions of one of his most iconic photos, “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris), 1992, to his close collaborators Roni Horn and Julie Ault, and to Andrea Rosen. Did he do it as part of realizing an official edition (4+1AP), or before, or after? What do they show about how he developed and realized his work?

How is one considered a core work, while three are not? Is the largest print the most fully realized example of this poignant image, or the snapshot he gave to his queer artist friend? What do we lose when the three “non-work” prints go unshown, unconsidered, unmentioned?

But they’re not really missing; they’re just in the market. I saw a little Toklas flowers photo at Art Basel. And over the last 10-15 years, many objects from these non-work categories have appeared at auction. They’ve usually been priced far below the artist’s official work. Recently I met the buyer of the 1986 photo above, known either as Untitled or Untitled (Crucifixion), and signed and numbered as “an edition of 3 artist proofs.” It once belonged to Blake Byrne, the LA collector who donated his Felix Parkett billboard to the Wexner, where it was installed and later demolished.

There are four tinted photos of the same crucifixion sculpture in the Additional Materials section: two red, one blue, and one green. The sculpture is of Eulalia di Merida, an early Christian martyr, made by Emilio Franceschi in 1880. It’s in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, where Felix traveled with his partner Ross Laycock in 1985 and/or 1986. Were these tinted and cropped photos souvenirs for his friends? How do they relate to photos he took of other sculptures which made their way into works? The bluer one on top turns out not to match any dimensions or provenance from the CR. Though it’s clearly related, it might be a different work.

A photo that went unsold (twice) at Phillips in 2008 appears to be a larger, offset print from an edition of a 1985-1992 photo that’s listed as unique. Sounds complicated.

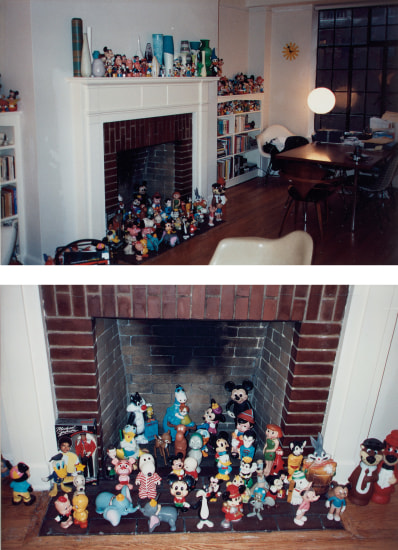

There are works, and categories of works, or non-works that aren’t in the CR at all, an almost inevitable situation, given how quickly it was compiled. The biggest is probably the Polaroid photos the artist gave to friends, colleagues, people he met. They track his social and professional interactions, a currency of encounter, a gesture of private generosity alongside the public offering of his work. Often accompanied by letters, notes, or the toys he collected, these snapshots feel very close to the images and material of the artist’s oeuvre; some are, in fact, included in or as works. One seems to have landed in the Met. But most are unseen, unknown, and undocumented.

Last year two signed snapshots of the artist’s toy-filled fireplace sold for $5625.

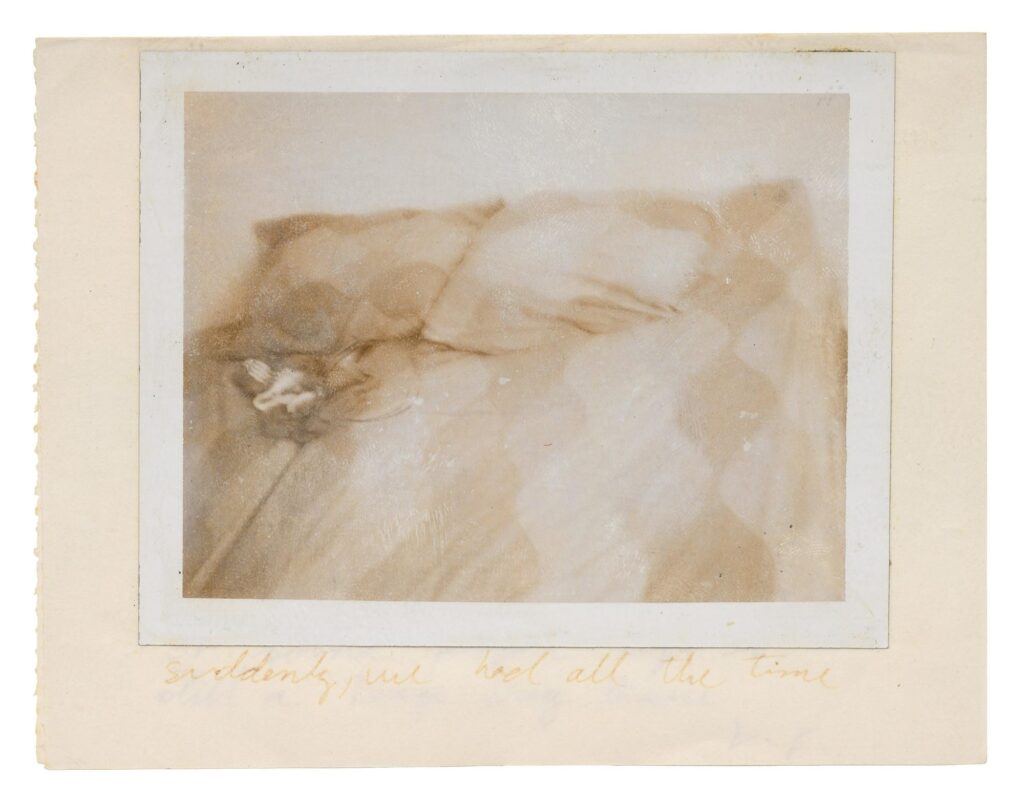

Last May an annotated Polaroid of a bed, which evokes one of Gonzalez-Torres’ most iconic billboard images, and which was originally given to a friend, Damien Fernandez, sold for almost $60,000, 10x its estimate. When it originally appeared at Christie’s in 2006, one of the first Additional Material pieces to come to auction, it had no reserve price. [Denver collector Ginny. Williams bid it up to $20,000.*] Maybe the market is not great at figuring these things out, but it does shake some of them loose from their hiding places.

But wait, there’s more. Beyond any CR category lies another pool of works, or potential works, in the artist’s archive. In 2007 curator Nancy Spector and the estate produced two Carrara marble pools, each 12 feet across, for the courtyard of the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The untitled work was based on an unrealized proposal from 1992-95 for an outdoor sculpture competition at a university. From Venice it landed in Potomac, on the terrace of Glenstone. It is one of three posthumous projects added to the artist’s oeuvre after the publication of the CR. [The other two are from an exhibition planned for CAPC Bordeaux that didn’t happen: an indoor installation of billboards, and a pair of reflecting pools embedded in the ground. The latter was constructed for a 2000 show at the Reina Sofia.] These three works appear on the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation’s website, at the end of the chronological list of works. By contrast, none of the objects listed in the CR as Additional Material or Registered Non-works are mentioned at all.

After rethinking my years-long dismay at these categories, I’d decided they were fine. Their criteria seemed clear enough, but most importantly they hadn’t disappeared these works completely over the years. But their exclusion and erasure going forward by the Foundation threatens to do just that. I know these works because I have the catalogue raisonée. But now, this sole source of info is out of print and mostly out of reach. Are the Foundation and the two galleries that now represent Gonzalez-Torres’ work seeking to broaden its perception and relevance while jettisoning an integral part of its larger context? [NEXT DAY UPDATE: NO, but see below.]

Just this morning, an announcement illuminates this strategy by describing a current show in Spain about Gonzalez-Torres and politics as, “not as a simple, biographical narrative, but rather as a way of complicating any essentialist reading of his work through a single idea, theme or identity.” That expansion of attention to his core oeuvre shouldn’t come at the cost of erasing large swaths of what surrounds it. Along with insights on Gonzalez-Torres’ biography, history, community, and practice, these missing categories can also reveal how an oeuvre is constructed and how a core is defined, both by the artist, and by those who come after him. Also, I do want that belt buckle.

UPDATE: The Foundation is working on documenting and presenting the Non-Works and Additional Materials as part of the Archive project. Discussion of it is here, amidst their larger effort to document the artist’s work, exhibitions, and correspondence. Some, even many non-works had been published previously, and though they were not part of the website redesign last year, they are coming (back). Meanwhile, non-works currently appear in exhibition documentation and checklists. There is an ongoing call in collaboration with the AAA for submissions of correspondence, including the gifts, toys, postcards, and snapshots the artist loved to send. I am, once again, fine with this.

*update: I’d misremembered the backstory of this bed Polaroid, and its appearance in the Add’l Materials list, and corrected it after publishing the post. FWIW, the CR lists smaller dimensions than the auctioneers, and describes it as an, “Image of shorts laying on an empty bed,” which, now that you mention it, yes, it is.

Oct. 2021 update: While researching early work by Richard Prince, I surfaced and re-read Bruce Hainley’s Artforum review of Michael Lobel’s exhibition, “Fugitive Artist: The Early Works of Richard Prince, 1974-77.” Prince refused permission to reproduce images of his work in the catalogue, and has removed mentions of early exhibitions in his own CV and histories. I’d forgotten that in discussing these works, Lobel referenced the “Registered Non-Works” category of the Felix CR, another example of where history, criticism, and art practice conflict or diverge. Hainley, meanwhile, referred to the Biennale and Spector’s posthumous realization of the pools. It’s a useful snapshot of the way things were seen and considered at that moment, and I certainly recognize how this post reflected my own lingering interpretations of these issues. It’s like living art history while trying to study it.