From her conversation with Saidiya Hartman, I learned about Dionne Brand’s poem, first published in 1990, “Blues Spiritual for Mammy Prater,” which is a response to a c. 1920 photograph of a 115-year-old formerly enslaved woman in Los Angeles:

what jumped out at me was how Mammy Prater’s figure in the photograph exuded a weight and patience, a knowledge about a future time when something might be recognized in the photograph. The poem talks about how she waited for her century to turn, until the technology of photography was ready to capture this something. It seemed to me that the statement she conveyed through the photograph was waiting to be understood by us in much later years. It could be understood in her time, but not sufficiently—not in in a way that could repay that pose. Only in the future could that pose be repaid by an understanding of what it took to sit there and be there.

Though the Library of Congress has several photos of her, most of the understanding of Prater today is due to Brand’s evocative poem. The only substantive account of Prater’s story I can find is on author Kimberly Tilley’s blog, Old Spirituals. She seems to recap an uncited 1920 article in the Los Angeles times about a US Census worker interviewing Prater on a farm in Los Angeles, and being shocked by her reported birth year: 1805. The story somehow involves a visit by J[ames] B[radley] Law, a descendant of the Darlington, South Carolina planter who enslaved Prater, who corroborated her stories and claims. The LOC’s photos have the upbeat, patronizing captions of the newspaper: “Mammy Prater, a 115-year-old ex-slave who is still hale and hearty.” “One hundred and fifteen years have failed to dim the keen eyesight of [Mammy Prater] this ex-slave” “Age has not dimmed Mammy Prater’s love for sweets.” Other images from the same shoot circulate in the stock photo archives.

Prater was 35 when the first photographic portrait of an American was made in 1840, a self-portrait by Henry G. Fitz, Jr. of Baltimore, who kept his eyes closed during the long exposure time required of the Daguerreotype process. [It was just discussed on The Week in Art, because it is on loan from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History to a Rijksmuseum exhibition of American photography.]

Prater was 13 when Frederick Douglass was born in 1818. Douglass, of course, escaped slavery and went on to make himself the most photographed person in the 19th century. Isaac Julien’s 2019 multi-channel portrait, Lessons of the Hour—Frederick Douglass, includes several scenes of him making photographs. It’s on view at the Smithsonian through 2026. When Douglass died in 1895, Prater was just 85.

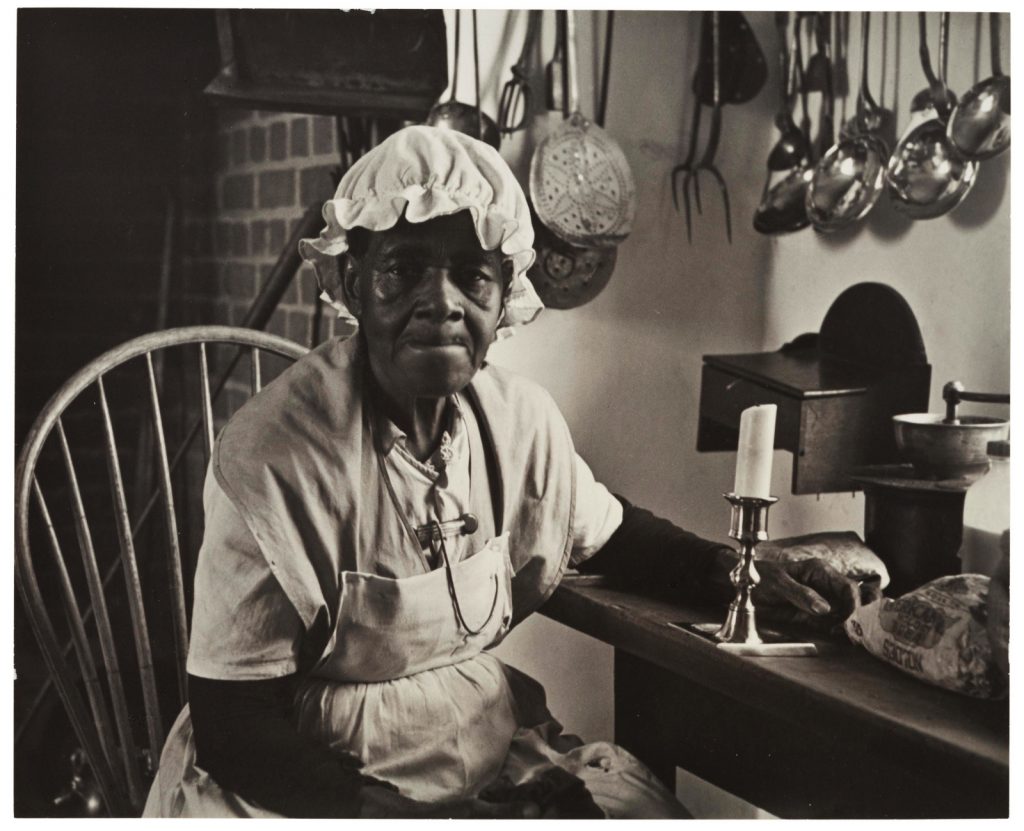

Prater was 60 when Mary Brown was born in 1865. Brown would be photographed 70 years later by Charles Sheeler, while she was dressed as “Aunt Mary,” a fictionalized enslaved cook she portrayed when she worked as one of the few Black performers at the Rockefellers’ Colonial Williamsburg in 1935-36.

When the Works Progress Administration began to gather more than 2,300 first-hand accounts and over 500 photo portraits Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers Project, 1936-38, Prater would have been 131. By that point, though, was through waiting.