While researching Arthur Dove’s inexplicably titled cow sketch, Public Enemy, I googled my way to the catalogue for Three Centuries of American Art, a labyrinthine exhibition at the Musée du Jeu de Paume organized in 1938 by The Museum of Modern Art.

The proto-blockbuster put every department of the museum to work. It included not only painting & sculpture and prints & drawings, but architecture, photography, and cinema—and Mrs. Rockefeller’s folk art collection.

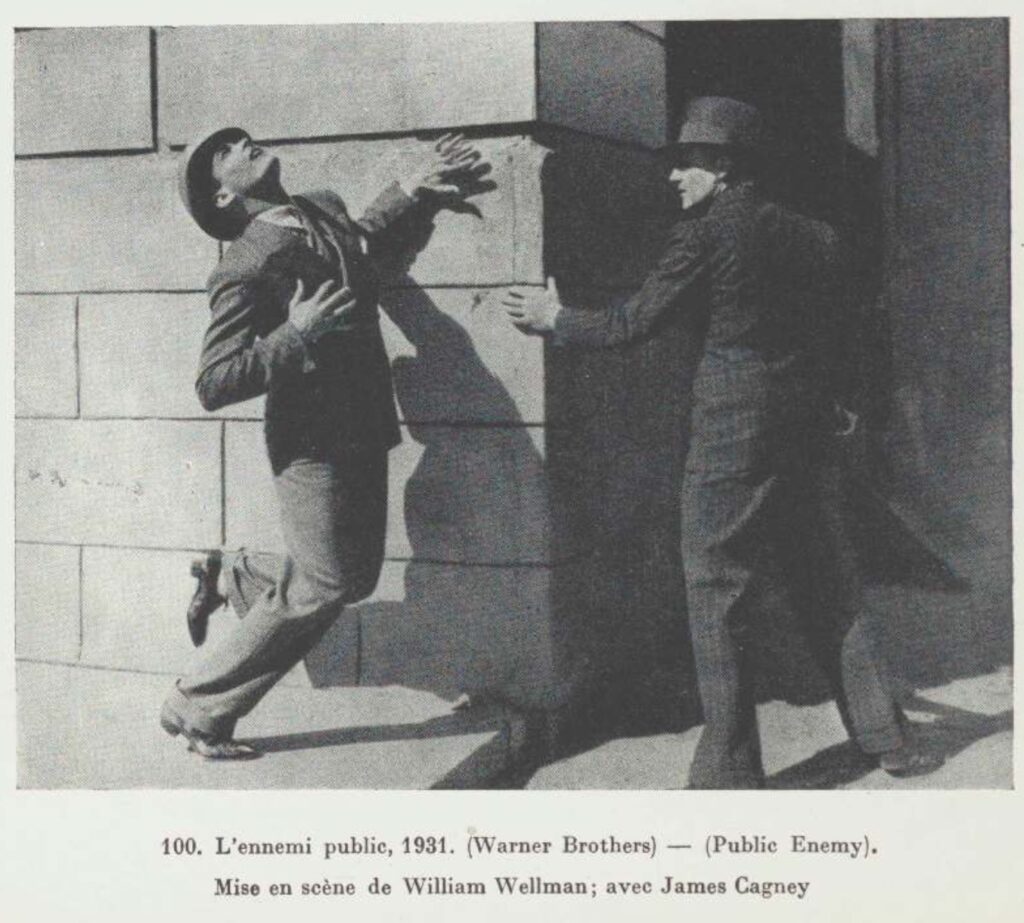

Honestly, the installation shots look a bit of a mess, and the use of photography in display, including the architecture section, looks more interesting than a lot of the photography section itself. But there was actually a public screening program [more on this in a minute], and a phalanx of film stills. And let’s be real: the still from The Public Enemy (1931) would make a Renaissance painting jealous.

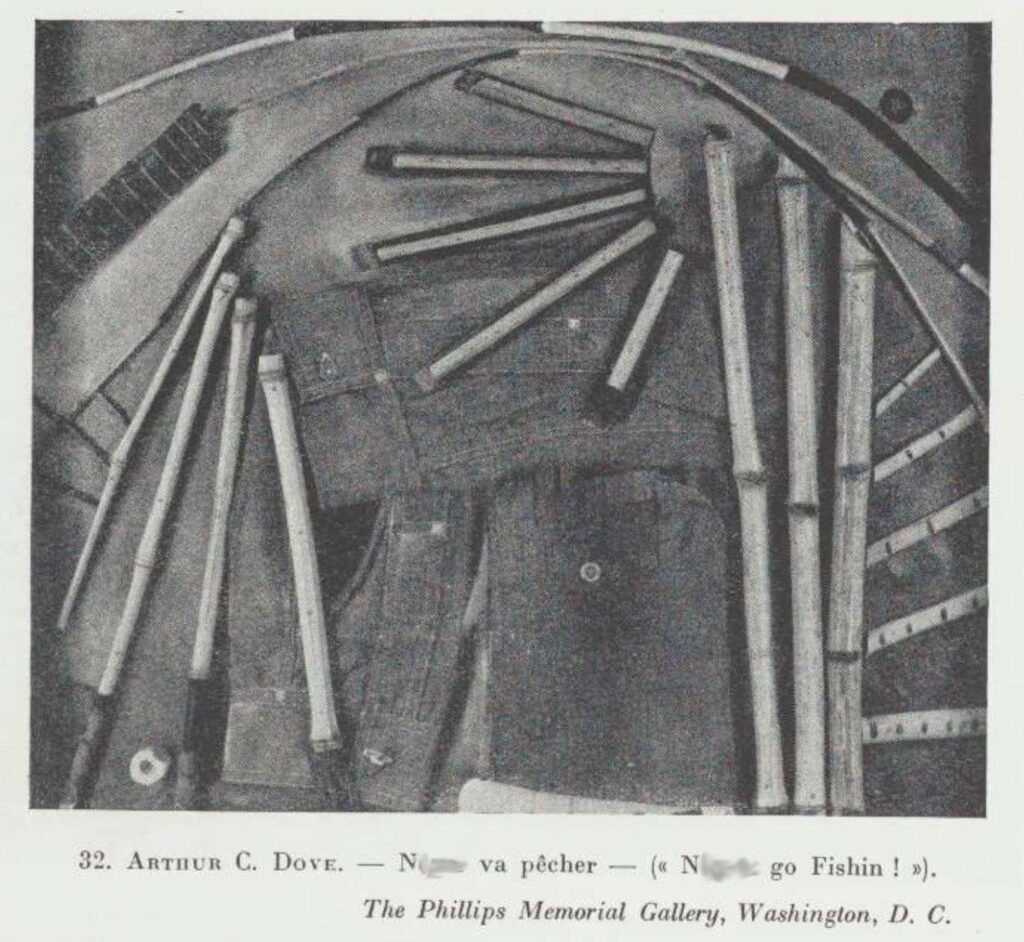

There was one work by Arthur Dove, and it is—oh, wait, ayfkm? It displaces Public Enemy as the instant and permanent winner of the WTF, Arthur Dove? Most Problematic Title award. It’s listed as belonging to Duncan Phillips, Dove’s biggest collector and most important supporter, and it is indeed still in the Phillips Collection, with the deracistified title, Goin’ Fishin’. [n.b. Unless they sold it since, MoMA didn’t own a Dove in 1938.]

The work is an assemblage of real objects—found and painted wood, bamboo, shirt denim, and buttons—one of a series Dove made alongside his paintings. Phillips saw this one early, missed it, and pursued it for twelve years. At Phillips’ prodding, in 1946 Dove made the last of a series of changes to the work’s title by dropping the N-word.

The result, ironically, ended up obscuring the work’s history, and that it was actually a portrait. In 2007, Nancy J. Scott published a close reading of the work, “Submerged: Arthur Dove’s Goin’ Fishin’ and its Hidden History,” that debunks some of the origin stories and interpretations of the piece—including those of Dove’s dealer Alfred Stieglitz. Scott restores the racism of Dove’s title and the contemporary discussion of his treatment of the subject, a Black man he saw fishing on a dock near his houseboat on the North Shore of Long Island. She also restores it to the context of the abstracted portraits was making in the mid-1920s, which included another of his houseboat and fishing neighbors, Ralph Dusenberry. That portrait, made of scrap wood, sheet music, and rulers, belonged to Stieglitz, and is now at the Met.

I’d figured Scott’s essay was the last word, the big reveal, and then I scrolled down on the Phillips’ page for Goin’ Fishin’, which lays out the racist origins, the context, history, and their own founder’s and institution’s involvement in it, up to and including their ignoring scholarship like Scott’s:

Only recently have scholars pulled back the curtain on the suppressed racist history of Goin’ Fishin’. Although the Phillips has been aware of these re-assessments, it has neglected to change its manner of looking at this work on its public platforms, including but not limited to gallery labels and website texts. In that regard, the Phillips has been complicit in the decades-long effort to ignore the racist origins of Goin’ Fishin’. These institutional omissions have effectively erased the fraught nature of this work’s history. The early titles are part of the historical documentation of this work and inform its original context.

The Phillips Collection is committed to shining a light on those parts of its history and collection that raise questions about race and difference, as these questions are not only part of the past but are still very much with us today. We understand that museums have a responsibility to use works like Goin’ Fishin’ to spark a dialogue and inspire critical thinking. We are at the beginning of our DEAI (Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion) journey, which includes, but is not limited to excavating the buried supremacist histories of objects in our collection. We are committed to reckoning with our past and preventing future harm. We do not claim to have the answers, but The Phillips Collection believes we must look with honesty and transparency at the full history of this work and others in our collection in order to begin seeing these works with new perspectives today.

(April 2021)

It’s been a while since I’ve teared up while writing a blog post, but here we are. Now back to the work.

[A few minutes later update: Because this blog is dedicated to me discovering things other people have written whole-ass books about, I am very pleased to learn from Jonathan Lill [@muslibarch.bsky.social] that Catherine M. Riley’s book, MoMA Goes To Paris in 1938: Building and Politicizing American Art (UCPress, 2023) not only exists, it apparently rocks.]