Even though it was a film [still], The Public Enemy (1931) that brought me to Three Centuries of American Art, MoMA’s ambitious 1938 Paris exhibition, I was not prepared to find an actual screening room at the end of the 85-pic slideshow of installation photos from the Musée du Jeu de Paume. But here it is.

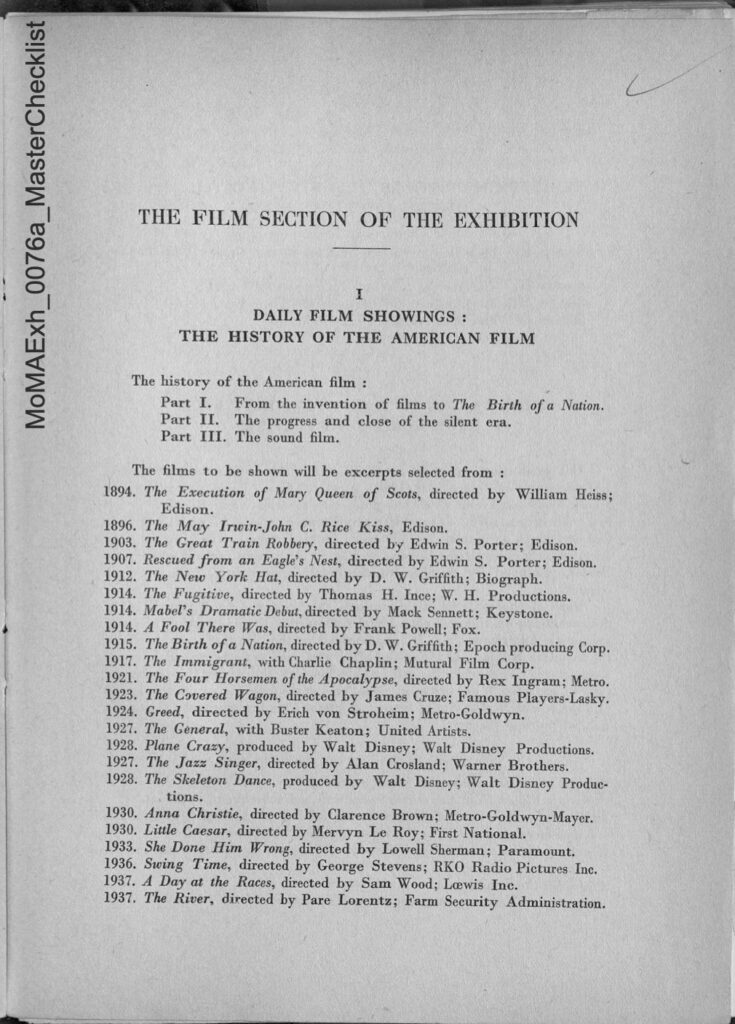

The sweep of MoMA’s exhibition included installation photography, fine art [sic] and historic photography, and film stills, but also cinema. And in a gallery, not a theater. What did they show? Here’s the program from the final checklist, which tells the “History of American Film” in three acts, using excerpts from 23 titles:

Part I. From the invention of films to The Birth of a Nation.

Part II. The progress and close of the silent era.

Part III. The sound film

I’m sure it’s wild because the French are certain they invented cinema; and because sound was barely a few years old in 1938; and because the idea of Birth of A Nation as a cultural landmark kind of hurts extra hard these days. But it’s also wild because for the last twenty+ years the Musée du Jeu de Paume has been reorganized to focus on photography, cinema and media, and this janky setup may have been the first of its kind.

[A few minutes later update: Because this blog is dedicated to me discovering things other people have written whole-ass books about, I am very pleased to learn from Jonathan Lill [@muslibarch.bsky.social] that Catherine M. Riley’s book about this exhibit, MoMA Goes To Paris in 1938: Building and Politicizing American Art (UCPress, 2023) not only exists, it apparently rocks.]