I just counted a thousand sheets of prints, and yet the Gerhard Richtermaxxing that kicked in around Panorama, his 2011 Tate Modern retrospective, still keeps surprising me.

There were the giclée prints of the Cage painting in the gift shop. Which led directly, I’d argue, to HENI Productions’ massive Facsimile Object operation, which unleashed thousands of Richterian objects on the world. [Including, most recently, mini versions of the Cage grid prints.] All these works are permanently installed in my head, and now I need to open another wing.

I’ve now seen three works from Museum Visit (2011), Richter’s largest series of overpainted photographs, with a provenance of Tate Modern. So were these sold to Tate friends and donors? Were they being sold in the gift shop, too? It was a veritable Murakamitown in there.

In the run-up to Panorama, Richter made at least 235 photos for Museum Visit at three locations around Tate Modern, with a different overpainting motif for each spot. They all seem to be mounted, titled, and framed identically. Marian Goodman had a grid of them in their booth in Miami in 2012, and I just assumed that was how they got out. Until now. Was Museum Visit also a fundraising project for the show? Or did Richter operate a ©MURAKAMI-scale pop-up at Tate without a peep of critical mention?

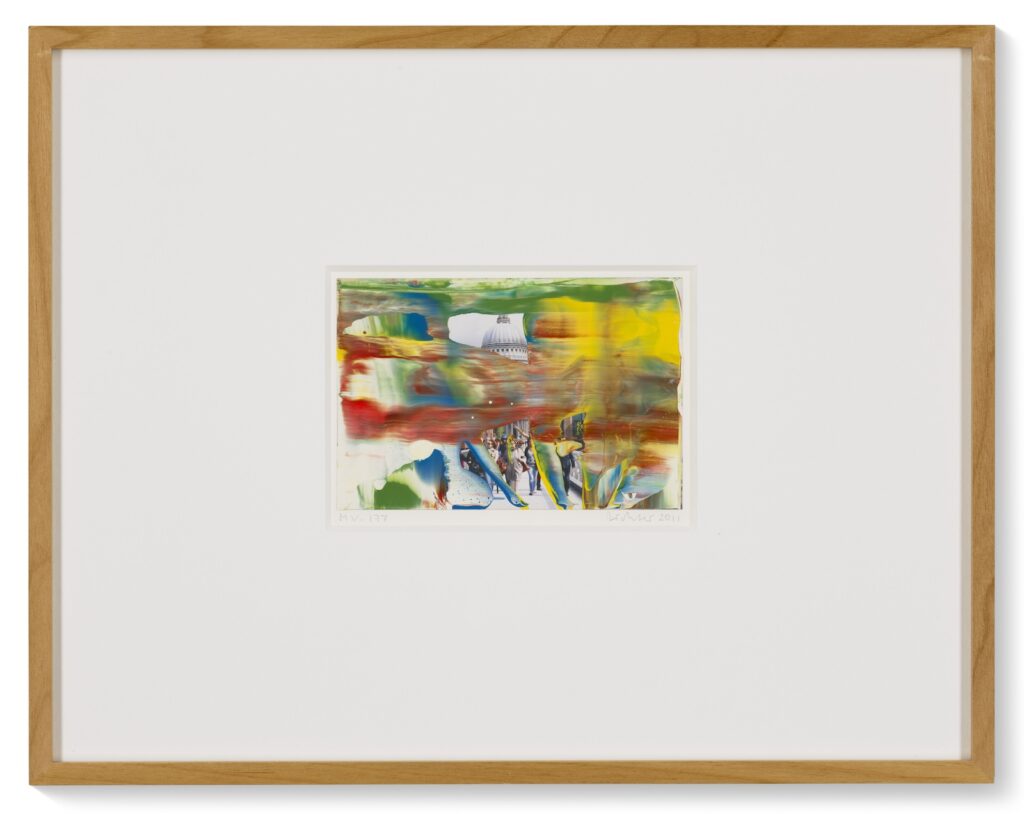

Yet it could not have been a simple cash&carry operation. MV.177, with the dome of St Paul’s peeking through the multi-colored paint, was apparently included in Richter’s 2012 exhibition in Beirut. [All the Museum Visit works were in the catalogue.] And it was one of 32 MV photos in Gagosian’s Overpainted Photographs show at Davies Street London in 2019. So it stayed close at hand.

Overpainted Photographs have this unique trajectory, created as personal, even seemingly private gestural experiments from rejected photos and leftover paint in the artist’s studio, immediately edited, then apparently given as gifts to friends, marks of connection and proximity, trickled out into the market by one local dealer, and accumulate over decades into a body of work that begins to attract critical and public attention. The early mass production series Firenze (1992) could be accounted for in the context of Richter’s artist book practice [or ignored.]

Reading Marcus Heinzelmann’s essay for the catalogue of the 2009 Overpainted Photographs exhibition at Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen, the series emerged from the surfeit of paint and photos that surrounded Richter at the end of each studio day. Ready material, random process, and ruthless evaluation converge in a moment, and barely half survive long enough to dry. Zooming out, this museum show and Museum Visit are the moment overpainted photos broke containment, the touch of the Richter’s hand, at scale. I want to watch him make them almost as much as I hate to watch Damien Hirst wander listlessly among an acre of tables, splattering paint across 1,000 sheets that get turned into a Heni Edition.

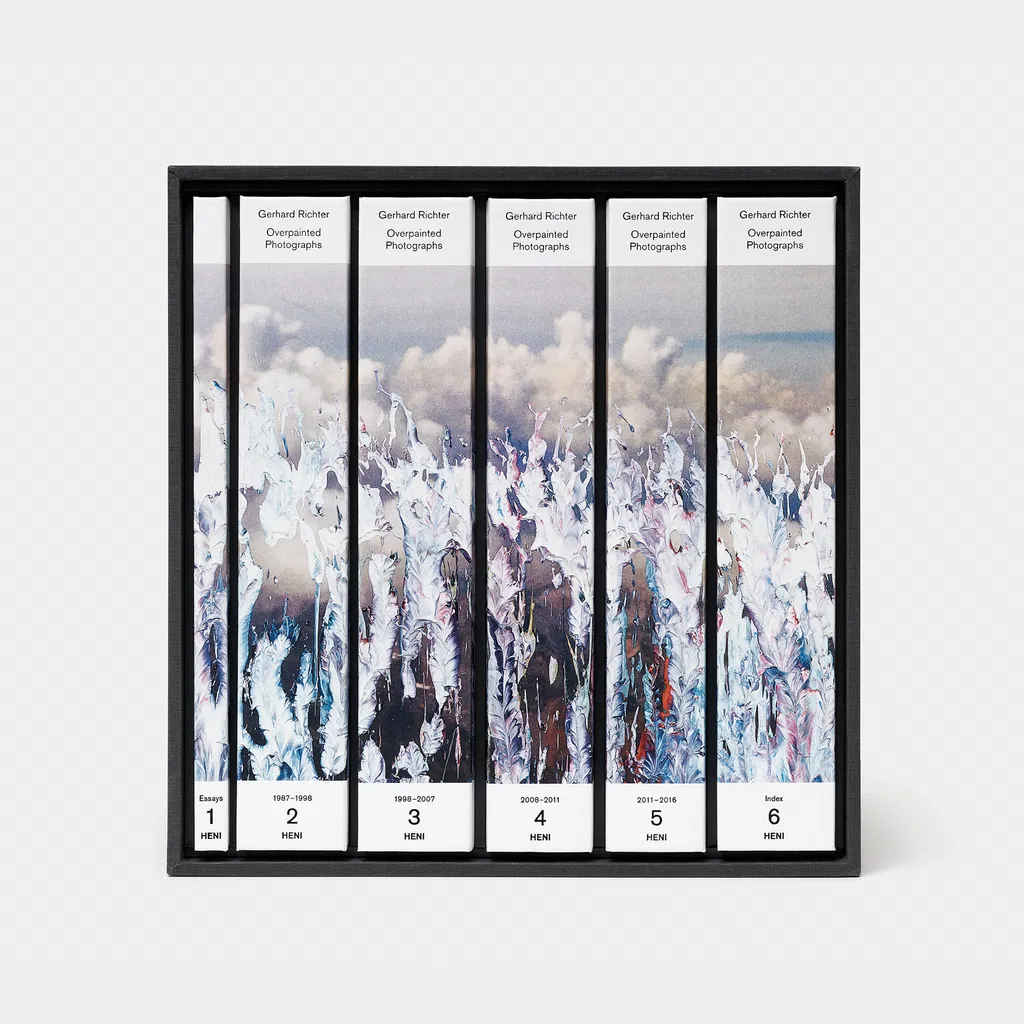

Speaking of which, the literature citations in a Christie’s auction listing is not how I expected to find out that Heni Editions partner Heni Publishing just released Gerhard Richter The Overpainted Photographs: A Comprehensive Catalogue? The six-volume [!] box set was released in the UK in December, and in the US like two weeks ago? Curiously not called a catalogue raisonné, TOP:ACC includes four volumes of works ranging from 1986 and 2016. So nine years later, I guess this really was the last overpainted photograph? To find out, you’ll have to read the book! It is $850.