On this, the anniversary of Rosa Luxemburg’s birth, I recalled the memorial erected to her and other anti-fascists, constructed out of the bricks taken from the walls against which they were shot in 1919. It was designed by Mies van der Rohe, built in 1926, and torn down by the nazis in 1935.

I have not yet found the testimony Mies gave in front of Joseph McCarthy’s House Unamerican Activities Committee, but I did find this paragraph from Dietrich Neumann’s foreword to his 2024 biography, Mies Van Der Rohe: An Architect in His Time:

“Politically, Mies was the Talleyrand of modern architecture,” historian Richard Pommer sarcastically noted, referring to the famously opportunistic diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, who was active under different masters before, during, and after the French Revolution. And indeed, a series of projects by Mies seem to suggest his indifference to political persuasions, be they the Bismarck Memorial, the Monument to the November Revolution [above], the Barcelona Pavilion, or the design for the Brussels World’s Fair pavilion for the nazi regime. Mies’s stand was hardly a profile in courage, but rather driven by opportunism and a desire to maintain the respect of his many left-leaning friends, while keeping his options open with conservative clients or the nazi regime. In the United States, he was suspected both of being a nazi spy and questioned by Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee about Communist leanings due to the Monument to the November Revolution.

Wait, what? Mies van der Rohe, whose most famous building was the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona World’s Fair, also designed a German Pavilion for the nazis at the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair? Was this not mentioned in Mies in Berlin, Terry Riley and Barry Bergdoll’s 2001 MoMA exhibition on the architect’s work through 1937?

Ah, it was, once, at the end of the catalogue entry [pdf, p.218] about the Memorial, as an example of Architektur Über Alles: “For Mies, clearly, architecture was an end unto itself, superseding political ideology.” [The catalogue incorrectly calls the date of the memorial’s 1926 dedication, 15 June, Luxemburg’s birthday, when it was 13 June, the anniversary of the date of her burial; murdered in January, her body was dumped in a canal and was not discovered until after the spring thaw.]

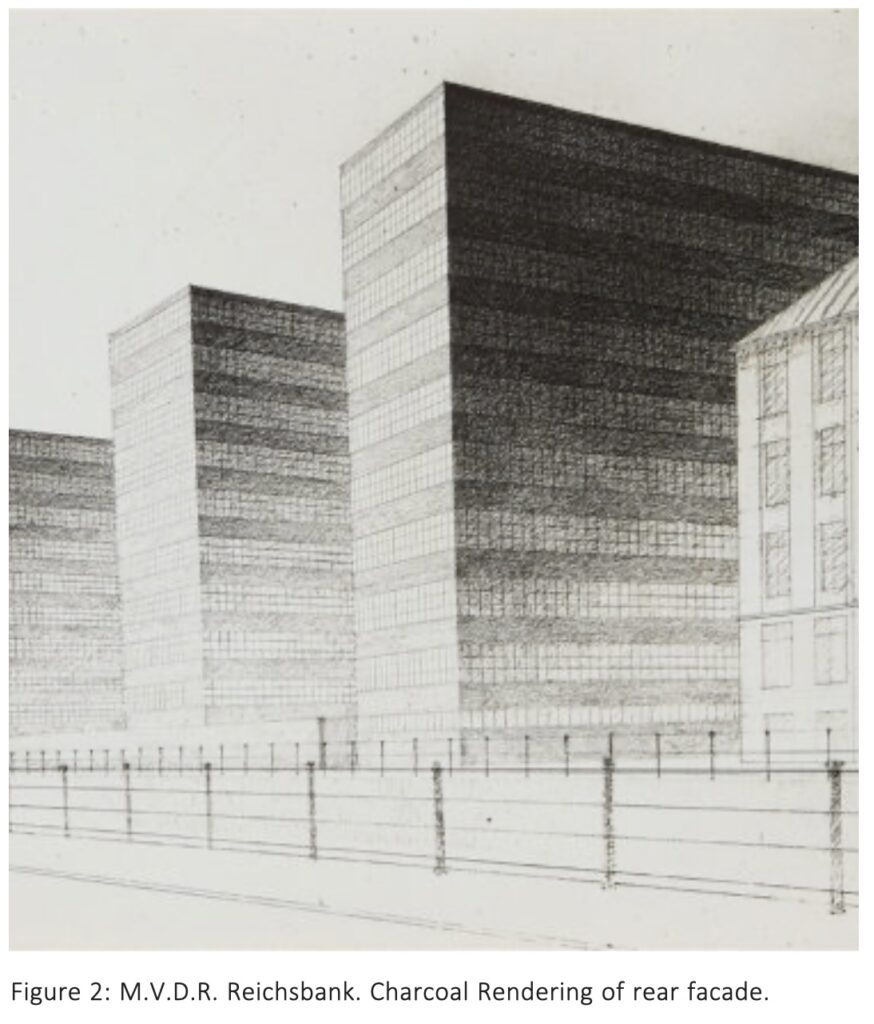

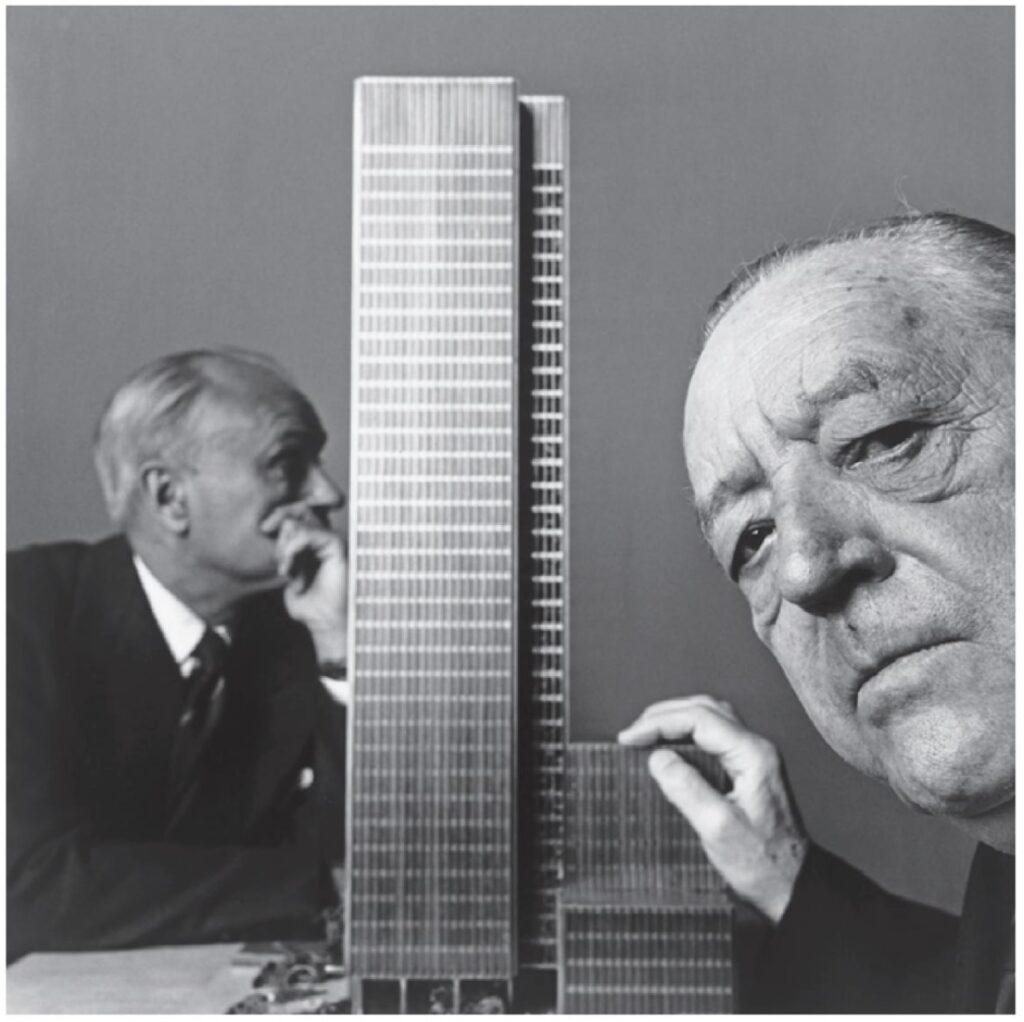

More attention was paid and a model was built for Mies’s 1933 proposal for the Reichsbank; its design competition was announced days before the nazis took power, and weeks later, the winners, including Mies, were all rejected by the country’s power-hungry new chancellor, Hitler, who was getting into everything.

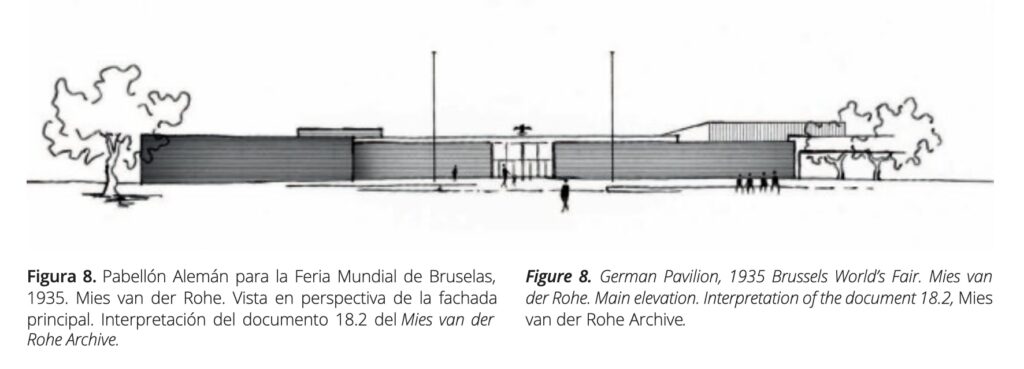

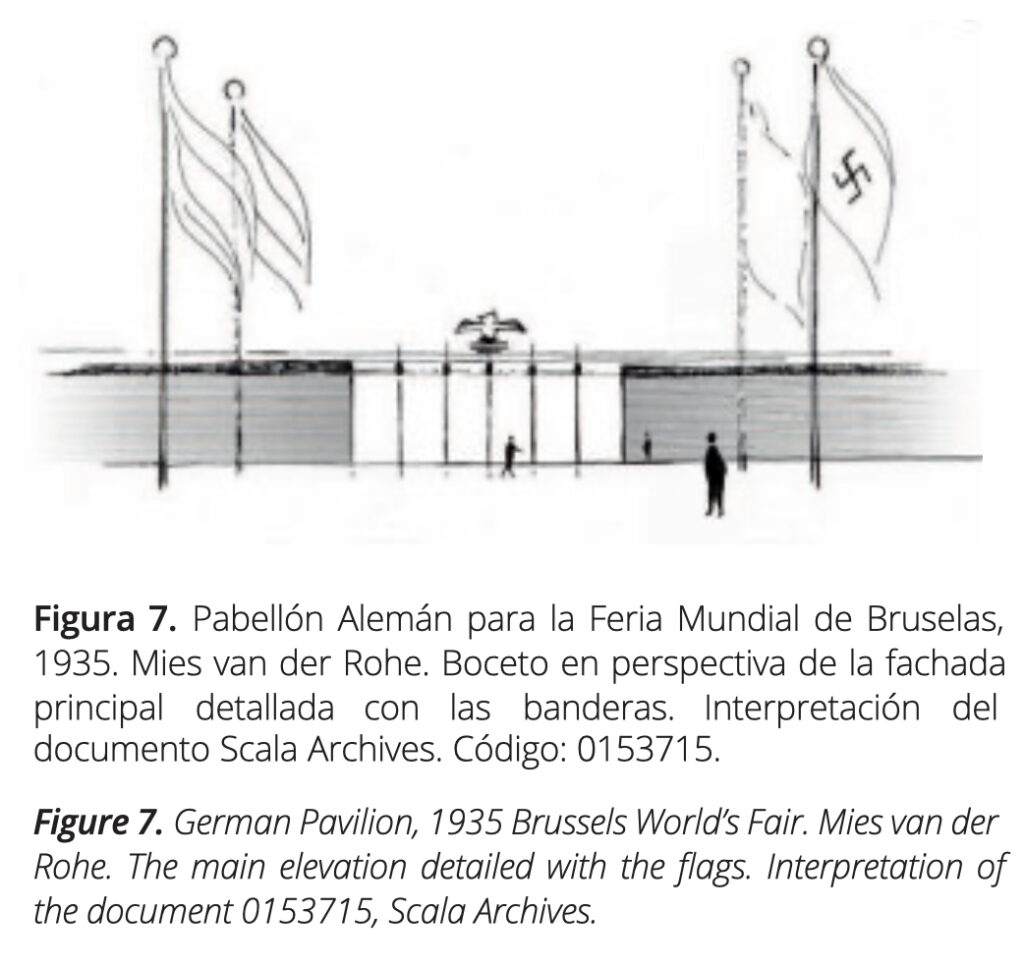

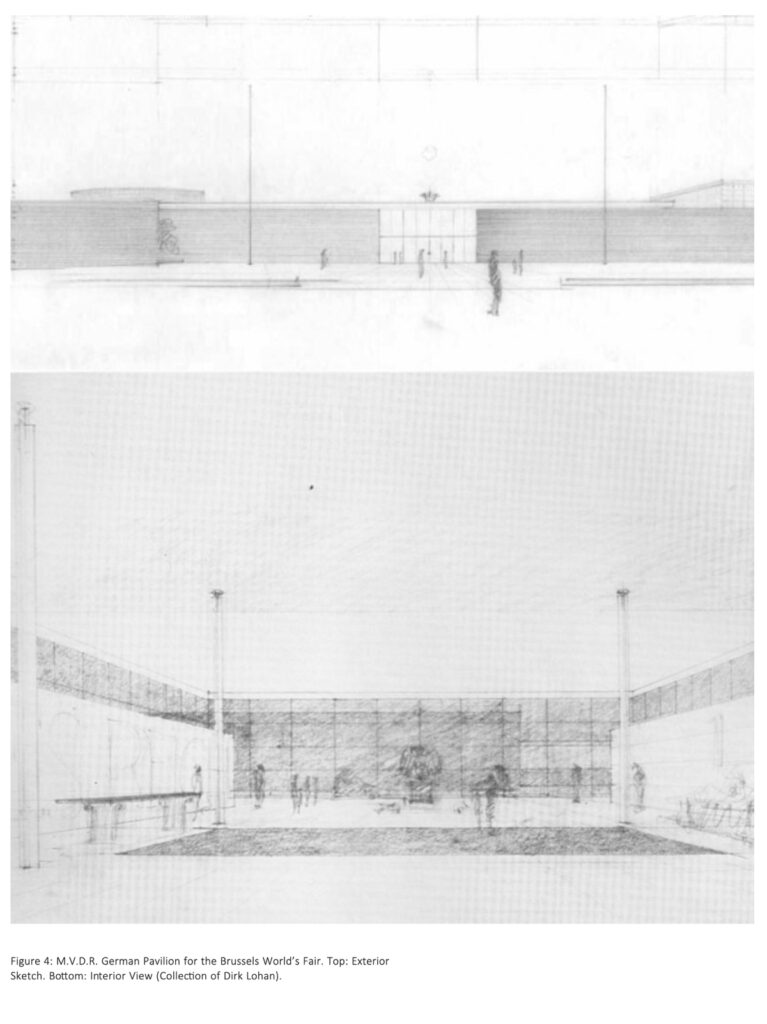

The most useful analysis of Mies’s second world’s fair pavilion is Laura Lizondo-Sevilla and José Santatecla Fayos’s 2016 essay in VLC Arqitectura. Basically, 1934 Mies was trying to stay in Germany and working, and was probably put on Goebbels’ competition shortlist by Albert Speers. His pavilion was moderism put into the service of nazism: a composition of large, unobstructed exhibition spaces, courtyards, and reflecting pools behind a [Luxemburgian?] rough brick and plate glass facade unadorned by anything—except swastikas, an eagle, and nazi flags. Nevertheless, Hitler rejected all the proposals as unsuitably unmonumental, and Germany skipped the fair.

Mies eventually left Germany for the US in 1937, where, oddly, he seems never to have mentioned his nazi pavilion. Lizond0-Sevilla and Fayos write that the correspondence and dozens of sketches were “forgotten in Berlin until the late 1960s,” and only entered MoMA’s Mies Archive posthumously, and only after the architect edited out the problematic bits: “He examined them and the three that had swastikas were given to his grandson Dirk Lohan saying ‘nobody can understand’. The rest were taken to MoMA after his death.”

In 2018 Andrew Ryan Gleeson presented a paper on the ethics of Mies’s nazi competition proposals to the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. The context was whether architects should help Build The Wall. Gleeson included a Mies sketch left with Lohan, in which DRITTES REICH [Third Reich] and an obliquely drawn swastika fill the two walls of the pavilion’s Hall of Honor, with a giant nazi eagle in between, and a glass curtain wall behind.

The VLC quote about the culling comes from William Huchting, whose 1996-7 paper, “The Building-in-the-Middle, Formally and Ideologically,” appears to be the first analysis of Mies’s Brussels Pavilion. [It’s in MoMA’s Archive, but also uploaded to academia.edu.] Studying MoMA’s archives and the sketches Lohan held onto, Huchting made renderings and built a model of the pavilion, and put it in context in Mies’s world. He believed it marked an important developmental moment for Mies between the Barcelona Pavilion and his campus at IIT. Also that, “Preliminary research into the Brussels Pavilion leads to the conclusion that Mies was not a nazi, any more than he was a communist for designing the Liebknecht-Luxemburg Monument or a capitalist for designing the Seagram Building. The research does, however, reveal a profound interest in a discourse amongst German conservative revolutionaries (This term may be found in the Glossary on page 8.)…”

Which, I’m gonna stop you right here, Bill. Because as fascinating the minutiae of pre-1933 German neo-conservative factionalism must have seemed in 1996, here Q1 of 2025, we don’t have the luxury of time to ruminate over whether the techno-authoritarian nationalists seizing control of the government are technically nazis.

But if being “in the middle” means just giving the fascist discourse a chance; serving on Goebbel’s Reichskulturkammer but only for a year; and designing a high-tech shrine to “power” and “fighting spirit” of the Third Reich, but it doesn’t get built, I know quite a few “centrists” who need to need to put down their DOGE government real estate prospectus and pay attention.