When I first made a modest proposal of cutting up Barnett Newman’s Voice of Fire, it was to make it more manageable to live with. I knew its purchase by the National Gallery of Canada in 1989 was controversial. When I suggested cutting it up to save it, though, I really did not have any idea of where the nihilist authoritarian government threat might come from:

So should Canadians ever face an arts crisis where, say a Taliban- or ayatollah-style regime takes over that is decidedly unsupportive of the kind of painting Newman practiced, I’d think cutting it down and dispersing the painting would be far better than burning it. Or bombing it, Buddhas-of-Bamiyan-style, out of existence.

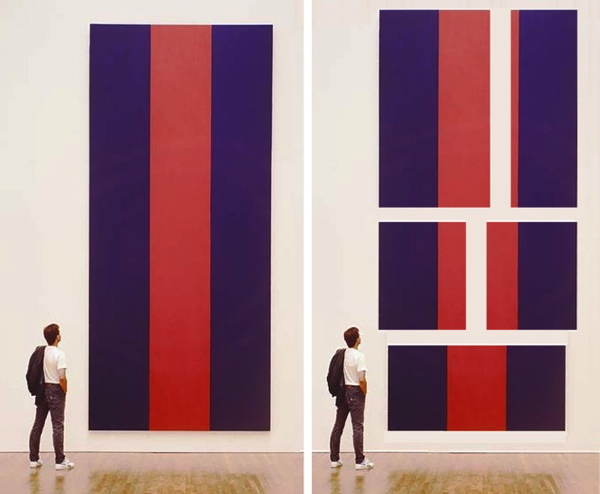

When I actually did start cutting it up, in early 2016, as part of Chop Shop, it was a direct critique of the exploitative market machinations of Stefan Simchowitz. And again, who could have known where that year would end up?

Is Limited

Still, how is it only when I saw Kristjan Gudmundsson’s artist book, 200 Pages on Barnett Newman, THIS MONTH, that I finally computed the terrible implications of chopping up a Barnett Newman painting? Because Gudmundsson surely knew it in 2001 when he made the book.

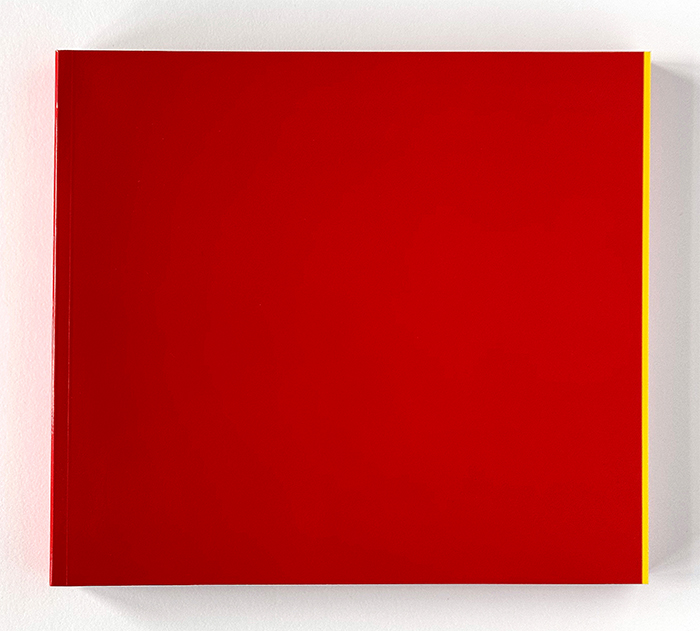

Voice of Fire is famous in Canada. When reproducing the entirety of a Newman painting over 200 pages, Gudmundsson chose the most famous Newman in Europe: Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow & Blue (1966). Well, he chose one of them: the first [Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow & Blue I] and smallest one [190 x 122 cm].

It’s not clear where I is, but the other three Who’s Afraid paintings are in German and Dutch public collections, and two of them have been attacked and damaged by freaks. One was basically so ruined by its restoration it became a political scandal in the Netherlands, which re-inflamed the idiot who slashed it so much, he went back to attack it again, couldn’t find it, and slashed another Barnett Newman instead. Is why they’re famous in Europe.

“It includes the exact ratio of the three colors of the painting. When you hold this book in your hands, you have the entire surface of the canvas in your hands,” explains Kees Van Gelder, the connoisseur who posted about his copy at The Archive is Limited.

I assumed this meant the book reproduced the painting to scale, but that is not the case: it reproduces the ratios. WAORY&B I is almost 94% red. 200 pages could be the minimum scale to have the yellow and blue sections printed as full, 27×24 cm pages. But that’s an assumption made without ever seeing the inside of Gudmundsson’s book.

While the R/Y/B ratios would differ, if the other three Who’s Afraid paintings were printed at the same dimensions, the resulting books would be 122, 188, and 255 pages, respectively. He’s had almost 25 years and hasn’t made them though; I think Gudmundsson satisfied his interest with just the one book of the one painting.

In September 1983, Thierry du Duve wrote about WAORY&B and Newman’s radical attempt to liberate color—even the most basic color—from the prison of painterly obsolescence. Du Duve saw Newman’s paintings in the context of post-modernism’s two existential questions: what is painting’s future, and what is its relationship to the modernist past?

Between these two questions stands fear. There is the fear that early abstract Modernism, and all the futurist enthusiasm and revolutionary fervor it carried with it, must one day be severely judged by the tribunal of history as a naïve and monstrous hope that would give birth to all sorts of terrors. But above all, there is also the fear that if one is lured into making this judgment, one then gives up all hope and surrenders to those political and artistic forces whose only answer to avant-garde “terrorism” has always been the most massive oppression.

Honestly, I do not know what to make of this 9,100-word polemic, which includes at least one violation of Godwin’s Law, and which followed the first attack of a WAORY&B painting by less six months and predated the second by less than three years. I just wanted to post about a book that looked interesting, which seems to have been sitting, silent and inert, in the best art libraries of Northern Europe, and everywhere I turn I find a nihilistic authoritarian shitshow.

KRISJAN GUDMUNDSSON, 200 Pages on Barnett Newman, 2001 [thearchiveislimited, s/o Alex for the tip]

Previously, related: Untitled (Newman Twelfth Station Glitch I & II), 2013

David Diao On Barnett (and Annalee) Newman

David Diao: Barnett Newman: The Cut Up Painting