Visitor posted this comment from Richard Serra's 1974 interview with Liza Bear, quoting his own statement from the catalogue for Maurice Tuchman's 1970 show at LACMA, Art and Technology, about technology being "a form of toolmaking, body extension." Also, "Technology is what we do to the Black Panthers and the Vietnamese."

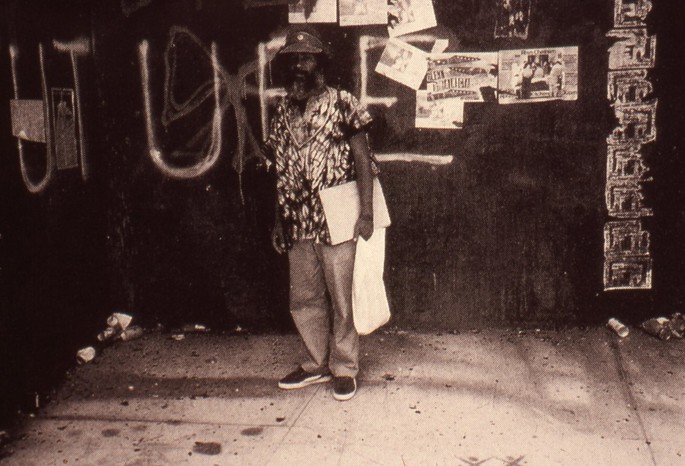

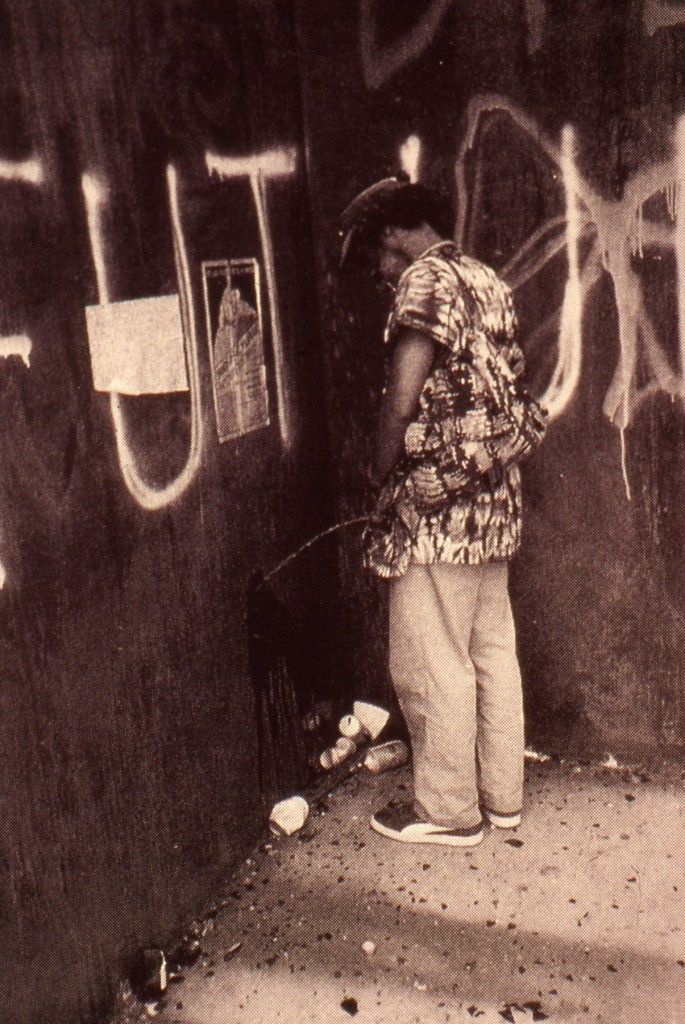

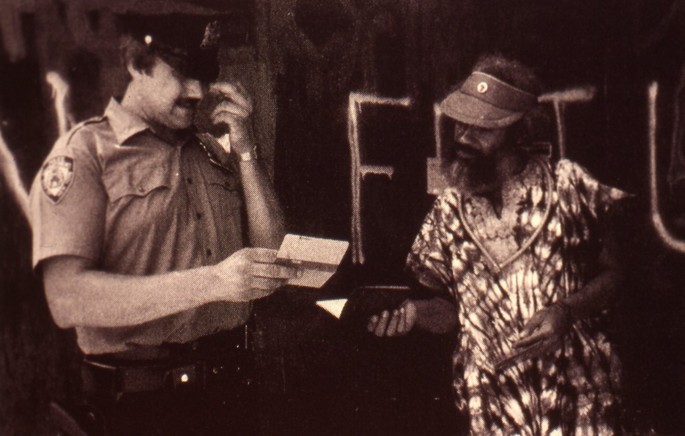

technology is david hammons pissing on your sculpture. pic.twitter.com/QPm5w2zysT

— visitor design (@visitordesign) August 30, 2013

He goes on to say that "It reflects my political responsibility to the public--not that I have any idealistic notions of swaying the masses through television. I think commercial TV is basically show business, and that means show business is used to reflect corporate America's interests."

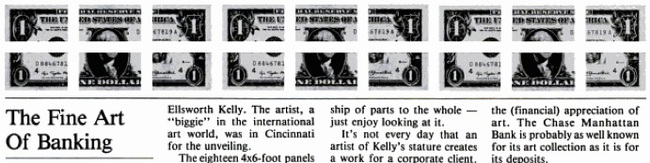

Of course, one of the criticisms leveled at Art & Technology was that it was using art to reflect those same corporate interests. Tuchman arranged for 64 men of the art and industry to pair up to produce artworks, which would be exhibited at the Museum, and also the US Pavilion at the Osaka 70 World's Fair. The results were mixed at best.

Roy Lichtenstein worked with Paramount to make 35mm painting/film installations. Warhol made some wacky lenticular rain machine. Rauschenberg made a bubbling pool of lubricating mud. Tony Smith tried to make a cave from thousands of cardboard tetrahedrons. And all of it went down when opposition to the Vietnam war and Nixon and the Establishment were hitting new nadirs every day. If the show was meant to heal, bridge, transcend, or even paper over the cultural chasms between art and the American corporate machine, it has to be considered a failure.

And yet, somehow I hadn't noticed this, and I can't remember ever hearing it discussed, the work Richard Serra made for Art and Technology seems like some of the most crucial of his career. I'll look again, but in terms of the artists' own practice, I think Serra made what turns out to have been the most important art in the show.

Serra was, remarkably, the seventh artist Tuchman tried to match with Kaiser Steel Corp's Fontana mill. [Among the first six attempted matches: Smithson and di Suvero, which, sure, but also Jules Olitski and Len Lye, which, what?] He proposed work that would "be related to both the physical properties of the site and the characteristics of the materials and processes concomitant to it."

The three "categories" he envisioned were, casting, overlaying/stacking, and constructions.

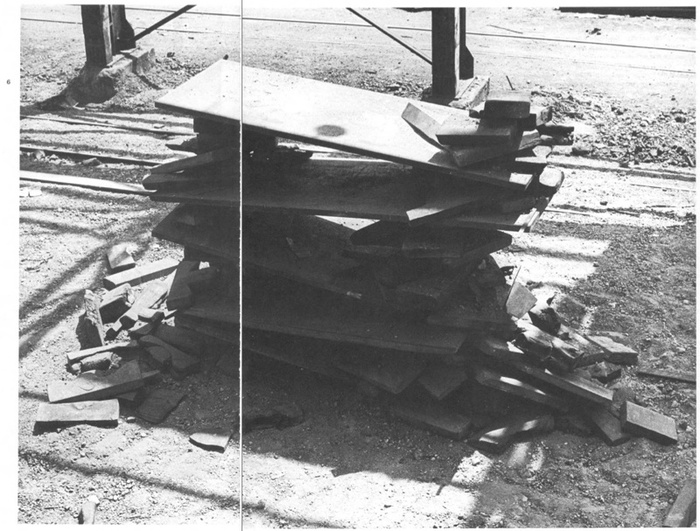

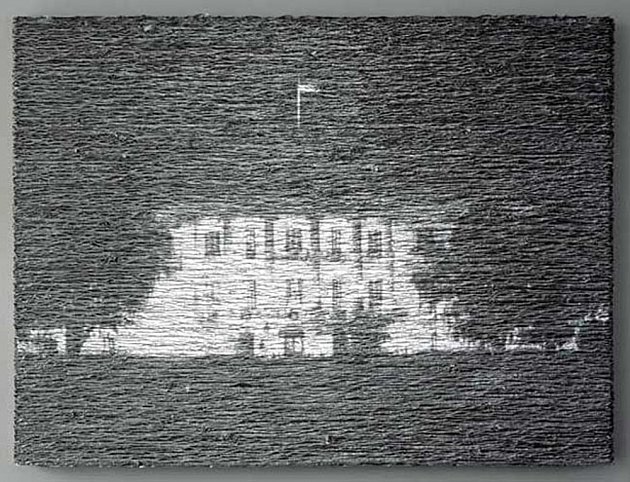

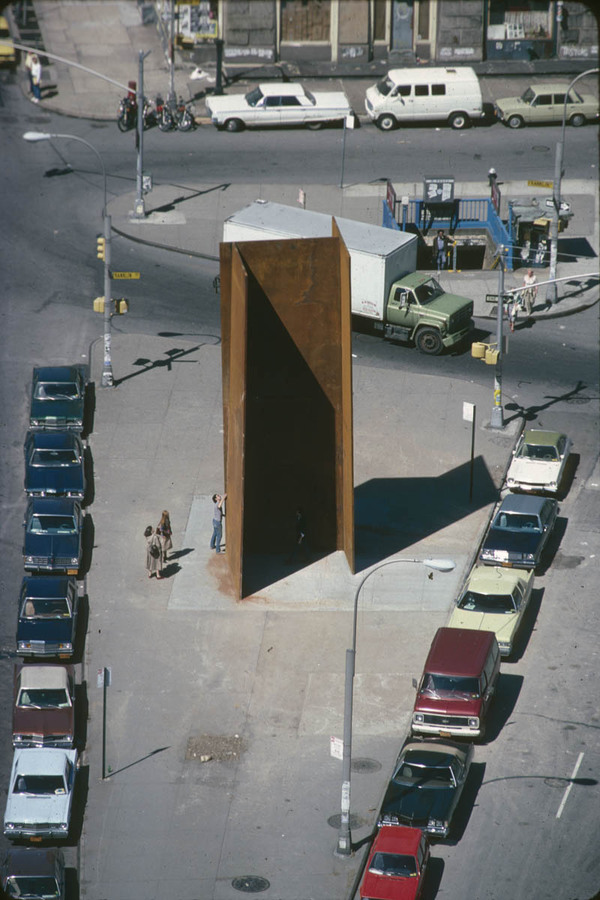

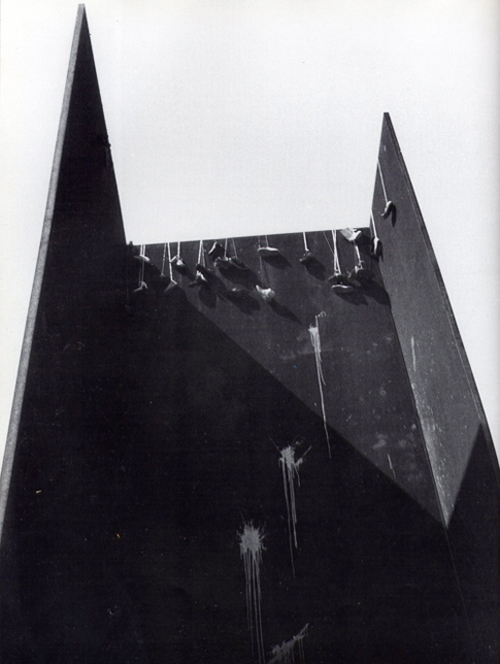

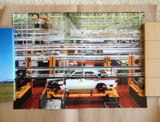

And that's just what he did. Serra worked nights with the crew assigned to him to get a feel for steel in its different forms, for the site, and for the processes available to manipulate the material. After several weeks working in the skullcracker yard, where scrap steel was moved around with a giant magnetic crane for reprocessing, he used the machinery to execute 12 different constructions [or 20, depending] within two intense, final weeks. "The procedure would be to erect a piece, and, if he considered it successful, to have it recorded photographically when possible. The structure was then dismantled."

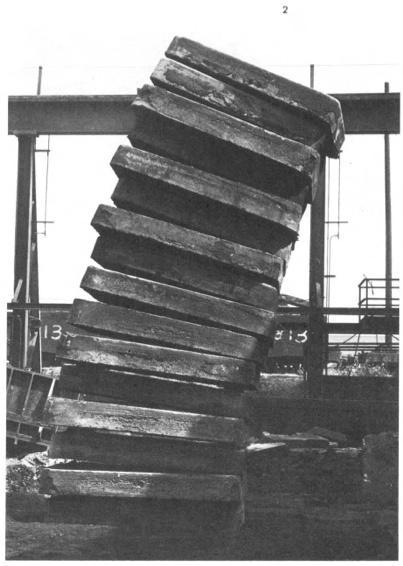

Stacked Steels Slabs (Skullcracker Series), 1969, constructed at Kaiser Steel, Fontana, CA

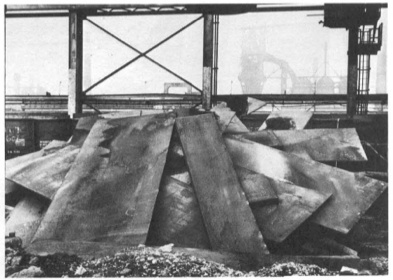

The first of these pieces is probably the best-known, a leaning stack of sixteen 6-ton slabs of cast steel known as stools, the photo of which has circulated under the name, Stacked Steels Slabs (Skullcracker Series). These Skullcracker Series works became more structurally complex; Serra created loose piles of steel scrap, then propped large slabs against or on top of them.

He made counter-balanced structures with plates jutting out in various directions. They remind me a bit of the block towers architect Eliot Noyes made to demonstrate balance in a 1955 educational film. I'm sure, of course, they were completely different.

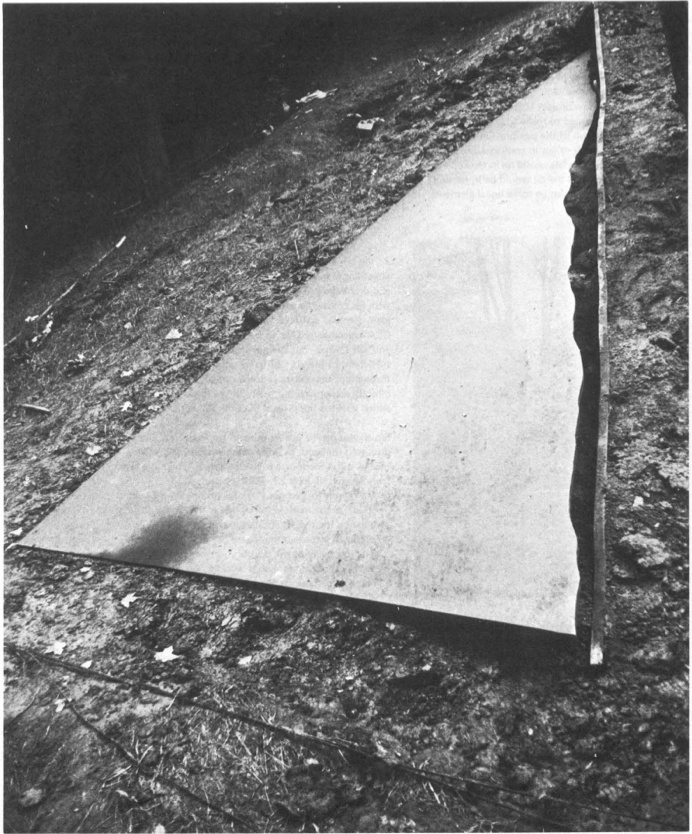

After a second, less successful stay in 1970, Serra agreed to return in the Spring of 1971 for the actual LACMA show. He would erect a Skullcracker Series at the museum, and also install "a piece related to his more recent thinking; the idea derived directly from what he had learned about steel at Kaiser."

His idea was to measure a site and install a steel plate, which would be cut along the edge of the ground, thereby taking the contour of the topography into which it had been installed.

Though the cutting is, I think, unique, a form of drawing, this creation of sculpture that marks the contours of a site is immediately, obviously recognizable as central to Serra's work at the time. He was doing it at that exact moment in St. Louis with Pulitzer Piece, and in Ontario with Shift. And he says that it all came "directly from what he had learned about steel at Kaiser." [Those links are both to Tyler Green's Modern Art Notes, who's written one of the very few art-aware accounts of actually visiting Shift.]

Serra's steel mill-based practice is something else that, in the intervening decades, has become central to Serra's work. In interviews, it's usually explained by biography, by early factory jobs in college. But those jobs didn't get a mention in Tuchman's Art & Technology catalogue, and Tuchman's complicated show rarely gets credited for arranging the corporate collaboration at Kaiser Steel that gave Serra his first studio in a steel mill.

Previously, related: Stop & Piss: David Hammons' Pissed Off