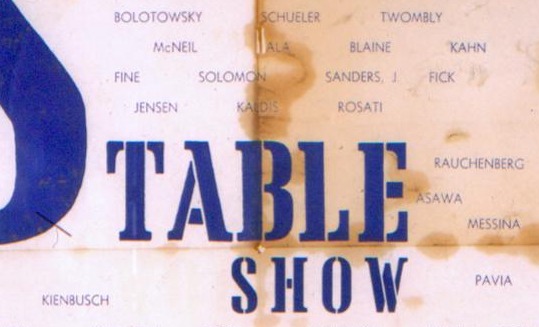

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Which is funny, because the greatest book I’ve found on Jasper Johns so far is by Michael Crichton. Seriously, with his 1977 book, Jasper Johns, created for the artist’s mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Crichton defined the exhibition-catalogue-as-pageturner genre.

After my most recent visit to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art last week, I had a few minutes to spare, so I ducked into the Museum of American Art Library across the hall to flip through Crichton’s catalogue and to see if there was any mention of Short Circuit in the supposedly exhaustive catalogue for Anthony d’Offay’s 1996 show of Johns’ Flags. [There wasn’t, and though it had a couple of good ideas, David Sylvester’s essay was uncharacteristically uninteresting.]

Well, flipping through Crichton’s book was riveting. I could only read a few pages, but it felt like a mystery, a suspenseful, personal investigation into the artist, his thinking, his process, and his work. It was chock full of quotes from people who know and work with Johns, evidence of Crichtons’ conversations and interrogations. I wanted to read every one. And it was only the recurring image of my kid waiting, alone, on the curb outside her pre-school, wondering why her daddy had forgotten her, that forced me to stop. It’s an intense, infectious curiosity that I admit I haven’t really felt towards Johns’ work before.

In the course of this recent, somewhat intense look at Early Johns, I’ve been struck and sometimes a bit put off by the artist’s apparent/reported hermeticism, his opaqueness. Not that I want art spoon-fed to me, or served up like some all-I-can-consume Baselian buffet. But if Johns wants to be obscure, closed, personal, private–yeah, I’ll go with closeted–then fine. Far be it from me to pry. And far be it from me to take advantage of that reticence by projecting my own theories and interests and speculations on the artist and his work, as a great deal of critical writing about Johns seems to do.

But while he addresses and acknowledges Johns’ seemingly impenetrable work and persona, Crichton also quotes a close friend saying something like, no, “Jasper wants to be understood.” [I’ll look it up later when my copy of the catalogue arrives.]

the very flaggish, hinged In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961, Art Inst. of Chi., via NPG

And that, coupled with the remarks from the curators of “Hide/Seek” that it was the first time Johns has ever allowed his work to be seen in a queer context [that link it to Michael Maizels’ discussion of the show], makes me feel that this longer, closer look at this painting–these paintings–is not just alright, but right. And that Johns would agree.

Anyway, the point is, buy this book. No, no, the point is, Johns rewards close, intense looking, and Short Circuit, both in its original state and throughout its fraught, altered history, feels like a key touchpoint in the works, lives, and careers of these artists. And it turns out that no one has gotten its story totally straight yet, not even Michael Crichton.

There is a note in Crichton’s Johns story that begins:

As a curious historical incident, a Johns painting was seen at the Stable Gallery in 1956, as part o a Rauschenberg painting.

Actually it was 1955. But then there’s this bombshell:

Leo Castelli later acquired the Rauschenberg with the two doors. He kept the painting in his warehouse. One day he examined the painting and dsicovered that the Johns flag had been stolen.

Wait, what?? Castelli bought Short Circuit? So it was not, after all, in Rauschenberg’s personal collection his whole life after all. And I only find this out after I leave the Castelli Archive. I wasn’t even looking for this kind of stuff. While it explains what Short Circuit was doing in Castelli’s warehouse, it doesn’t explain when Bob sold it, or why Leo bought it. Or why or when Bob got it back.

The artist Charles Yoder told me last month that Short Circuit was in Bob’s collection–and had Sturtevant’s replacement Johns Flag when he went to work for Bob in 1971. [Though the first published mention of Sturtevant I can find is still the Smithsonian’s 1976 catalogue, which ended up using Rudy Burckhardt’s original, Johns-era photo.] I guess I’ll have to get back to the Archive and look for Castelli’s own collection records. And his correspondence with Bob. And then look for the 1967-8 Finch College Collage checklist and/or catalogue, to see who was listed as the owner of Short Circuit, which was, remember, still described as containing a Johns Flag behind its nailed-shut doors.]

So this means that sometime between–well, we really don’t know when it was, just sometime before June 6, 1965–Castelli bought Short Circuit. And found the Johns Flag missing. But Crichton’s not through. “Castelli recalls a final incident in the story,” he writes:

Years later, a dealer–we do not need to say who–came to me and said, “Someone has brought me this Johns painting and I don’t kno wit, and I wondered if you could tell me about it, the date and so on.” I knew immediately what it was; it was the stolen painting. I said, “The painting has been stolen and I would like to keep it right here. I don’t want it to leave my gallery.” But this person said he had promised the person he got it from, and he didn’t feel he could leave it with me, and he said he would have to talk to the other person, and he was very insistent. So I said, “Well, all right.” I never saw the painting again.

“Castelli recalls”! “We do not need to say who”!

Well, this saves me a trip into Calvin Tomkins’ archives at MoMA; because I will bet that Crichton’s footnote is the source for the secondhand version of this incident Tomkins included his 1983 Rauschenberg bio. And where Tomkins ended broadly–and obviously wrongly–with “and nobody has seen it since,” Crichton nails the quote from Castelli: “I never saw the painting again.”

Which puts us back to where this whole thing started. Except that I think I now know–because I have been told by people who would know–who that dealer was, and who he was presenting the painting for. And based on some interviews I’ve done since, I am pretty sure I’m right.

But that turns out not to be the same as figuring out when the Johns Flag went missing, or more importantly, where it went, and where it is now. And even when Crichton quotes Castelli himself as calling the painting “stolen,” and I’ve seen it mentioned [albeit as “lost”] in an insurance report, when Castelli had the painting back in his gallery–and had chance to get it back from someone he obviously knows–he let it walk out the door again.

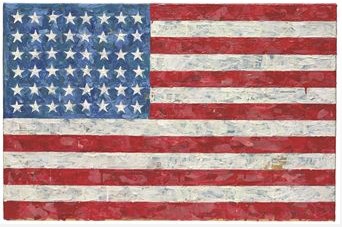

Michael Crichton died unexpectedly in 2008 while undergoing treatment for throat cancer. His art collection, including the Flag painting he bought directly from his friend Jasper Johns, which he considered his single most important acquisition, was auctioned last Spring at Christie’s. Mike Ovitz waxes a little hagiographic, and I deeply don’t get the Mark Tansey thing, but the video that Christie’s produced about Crichton and his passionate, intellectual engagement with art is really pretty good.

Measuring 17.5 x 26.75 inches, Crichton’s Johns Flag [above] is much smaller than the Flag which Castelli first saw in 1958 in Johns’ studio, an experience he later called, “Probably the crucial event in my career as an art dealer, and… an even more crucial one for art history.” It was slightly larger, though, than the Flag in Short Circuit [13.25 x 17.25 in.]. And it was painted between 1960-66, exactly the time when Short Circuit‘s Flag was being contested and lost–and shortly before Castelli got it back, and let it walk back out of his door. Crichton’s Flag sold in May 2010 for $28.6 million.