It’s exactly the kind of scribbled note I dug through five boxes of Smithsonian archival material hoping to find: “Someone may have loc. stolen ptg. So Charles will talk to Bob about it.”

Well, I talked to Charles about it. The artist Charles Yoder worked for Robert Rauschenberg for five years, until around 1975-6. So I called him, and unfortunately, he had no idea where the Johns flag painting was, the one which had been removed from Short Circuit in the mid-60s [Michael Crichton says before 1965.] He did say there was “scuttlebutt,” at the time, a general awareness that there was a Johns flag painting on the loose. But it never went beyond the, “I heard some guy was trying to sell it on the Bowery,” type urban legendry.

But though I didn’t find any smoking guns, or burned flags, in the records from Walter Hopps’ 1976 Rauschenberg retrospective at the National Collection of Fine Arts, I did learn some more interesting details about Short Circuit and its complicated history.

Like, for one thing, the 1955 combine was not actually shown in Hopps’ retrospective.

This turned out to be something I could have deduced from the foreword to the NCFA catalogue, which included a full-page entry on Short Circuit, but only, it turns out, as a reference.

Instead, I found out by culling through draft exhibition lists, notes, and memos, some by Hopps, but most by Florine Lyons, the assistant curator who appeared to have done much of the heavy curatorial and organizational lifting to bring the show together. At some point in mid-1976 [the show opened in October] the credit line for Short Circuit, which had read, “Lent by the artist,” was crossed out, and “Collection of the artist” was scribbled above it.

Which means that Short Circuit had, in fact, been planned for the exhibition, but it was removed. When? Why? The note above [from Lyons] was dated 6/30/76, and it contains a description of the combine [“…Inside doors, 2 ptgs: by Sue Weil, fake Jasper Johns [sic/heh]…replica by Elaine Sturdevant [sic]”‘ and its condition [“needs restoration”].

It was gone by the end of July, though. A couple of memos imply that Short Circuit, which was in Rauschenberg’s collection in New York, would be a substitute for Interview, a larger, similar, paintings-and-doors combine the Smithsonian was trying to borrow from the Panza collection. Panza’s eventual agreement to lend Interview which is now in MoCA’s collection may have made Short Circuit unnecessary. Factor in the work’s condition, and its altered state, and it may have been easier to cut.

Another thing I found is that there was confusion for a couple of months, from March through May, about which work Short Circuit even was, and when it was made. Apparently, Bob had told Susan Ginsberg, an art historian contracted to prepare his chronology for the exhibition catalouge, that Short Circuit was actually a 1961 combine called, Cabinet Piece. Cabinet was another combine-with-doors, which dealt, Bob explained, with his earlier work or motifs. But he also said it had been destroyed. For several weeks of drafts, Short Circuit was referred to as “1955/1961?” and “Short Circuit/Cabinet?” Ginsburg eventually decided that Bob had mis-spoke on the title/date for Short Circuit–or that she’d misunderstood him.

The thing about Short Circuit not being in the show was a surprise; what I’d actually decided to dig for was the story of the catalogue entry for Short Circuit which:

- Included the earliest mention of Sturtevant’s Johns flag replica, without saying when it was put in.

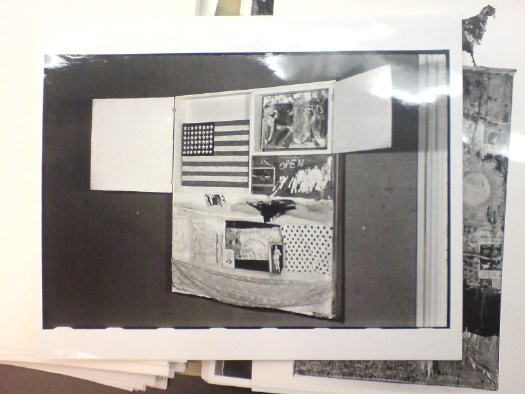

- Nevertheless used an early b/w photo that included the Johns flag [above].

- Had some unusually personal, even slightly anguished, but unsourced quotes from the artist about the combine being “a double document,” and about him wanting to paint the flag himself some day as “therapy.”

On most of these fronts, my archive diving came up empty. Charles Yoder did tell me, though, that Sturtevant’s flag was in Short Circuit when he started working for Bob, around 1971. [When the work was shown in 1967-8, the cabinet door was nailed shut, and press accounts said Johns’ flag was behind it, even though it had been removed by 1965. Which leads me to think Sturtevant’s flag might have come afterward, between 1968-1971.]

As for the photo: it’s possible, even likely, that once Short Circuit was cut from the show, there was no push to get a current photo for it. There was also no discussion, at least in the notes, of how the work might be different with Sturtevant’s flag in it instead of Johns’ flag, so the photo of the original 1955 state would have been sufficient.

The real disappointment, I thought, was Bob’s quote. I’d hoped to find a longer interview transcript, or notes, from which it had been pulled, but there was nothing; the quote just appears, handwritten onto a draft of Ginsburg’s chronology with no source, no date, no mention, even, of who he said it to:

“Some day I will paint the flag myself to try to rid the piece of the bad memories surrounding the thieft. Even tho E. Sturdevant did a beautiful job, I need the theropy.”

But as I kept on reading, and seeing other notes, and memos, and letters, and revisions, I realized that handwriting, that spelling, was from Bob himself.

A couple of other notes Ginsburg made seem particularly relevant to considering Short Circuit and its relationship to Johns’ work. In one draft of the Short Circuit story, the phrase “a flag painting by Jasper Johns” was crossed out and replaced with “a painted flag by Jasper Johns.” In that seemingly insignificant gap lies the enormity of Johns’ 1958 breakthrough. From Leo Steinberg to Roberta Bernstein and beyond, critics and scholars have cited the importance of Johns’ flags and targets in shifting from the flat painting to the painted depiction of a flat subject. [When extended discussion of individual works was shifted from the chronology to the images section of the catalogue, the text had changed again, to the even more inartistic, “an encaustic image of a flag.”

Unfortunately, I didn’t write it down, but there’s a note from Ginsburg to the Smithsonian staff saying that Bob was adamantly opposed to listing out the contents and materials for each combine. The works should be seen and considered as a whole, Rauschenberg insisted.

While he didn’t mention Short Circuit specifically, I think the prevalence of this view would go a long way to understanding the complicated dual existence of Johns’ little painting: it may seem to be a work, a painting itself. And if it is, it’s an extraordinarily important one, the first Johns flag painting ever exhibited. But it may also/instead[?] be not that at all. It’s a piece, a part, a subsidiary component of a whole–a whole combine painting by Rauschenberg. It was subsumed into Bob’s work as completely as de Kooning’s erased drawing. Of course, it’s this duality, when considered in the mostly unarticulated context of the artists’ romantic relationship–and their bitter breakup, and the uneasy aftermath, and their fraught joint custody of their shared history–that makes this work so fascinating to me. That, and tracking down that flag, apparently last seen being peddled on the Bowery.

Previously:

Finch College is off the hook, and Holland Cotter may be right.

Holland Cotter says the flag was stolen in 1965?

the flag was stolen in 1967, when Short Circuit was exhibited at Finch College

wait, what? There was a Jasper Johns flag painting stolen? When? Where? Why? Whoa.