I’ve been writing this post in my head for months, years, even, but so many pieces have piled up in my browser tabs, it’s slowing my computer down. And plus, this weekend MoMA announced that they acquired and will exhibit Untitled (Free/Still), the original [sic] free-Thai-curry-in-a-gallery work, so it’s time to step back and look more closely at Rirkrit Tiravanija’s art practice. First, by starting with what we are fed. Here is a small sampling platter of familiar statements by and about the artist and his work:

“It’s part of what has been called ‘relational aesthetics,’ ” said Ann Temkin, chief curator in MoMA’s department of painting and sculpture. “Joseph Beuys created social sculpture; it’s the act of doing things together, where you, the viewer, can be part of the experience.”

That’s from MoMA’s press release in the NY Times.

You could say his art is all about building “chaotic structures.” Then again, it’s about lots of things; his work is so open-ended and departs so radically from the art market’s orientation toward precious objects, that it’s earned many labels, many – like utopian or chaotic – that only tell part of the story. But one that’s stuck, for better or worse, is French theorist-critic Nicholas Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics,” the idea of judging the social relationships sparked by an artwork instead of merely considering the object.

That’s Paul Schmelzer, now/again of the Walker Art Center, an early and frequent supporter of Rikrit’s work, writing in 2006.

Tiravanija’s art is free. You only need the experience. In fact, the essence of his work resides in the community, their interrelationships, and chance. Make art without objects, their purpose is a complaint against the possession and accumulation.

The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, which owns Untitled (Caravan), a 1999 plywood model of a camping trailer, with kitchen, above.

Rirkrit as quoted by Bruce Hainley in Artforum, 1996:

“Basically I started to make things so that people would have to use them,” he has said, “which means if you [collectors, museum curators, anyone in these roles] want to buy something then you have to use it. . . . It’s not meant to be put out with other sculpture or like another relic and looked at, but you have to use it. I found that was the best solution to my contradiction in terms of making things and not making things. Or trying to make less things, but more useful things or more useful relationships. My feeling has always been that everyone makes a work – including the people who . . . re-use it. When I say re-use it, I just mean use it. You don’t have to make it look exactly how it was. It’s more a matter of spirit.”

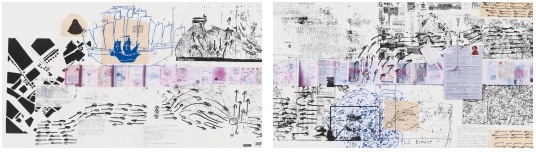

And here’s Faye Hirsch in Art in America this summer, perfectly teeing up her making-of story for Untitled (the map of the land of feeling), [above] an extraordinary 84-foot-long print edition Rirkrit has worked on for the last three years with students and staff at Columbia’s Leroy Neiman Center for Print Studies:

Rirkrit Tiravanija has never been known as a maker of elaborate objects. In a market-riven art world, he has remained, since the early ’90s, a steadfast conceptualist whose immaterial projects, enmeshing daily life and creative practice, have earned him a key role in the development of relational art. At galleries and museums around the world, he has prepared meals and fed visitors, broadcast live radio programs, installed social spaces for instruction and discussion, set up apartments–where he or visitors might live for the duration of a show–and dismantled doors and windows, leaning them against walls. At two of the three venues for his 2004 retrospective, the “display” consisted of a sequence of empty rooms referencing (in their proportions and an accompanying audio) his selected exhibitions over the years.

When Tiravanija does make objects, they are generally of a modest nature–most often multiples and ephemera connected with exhibitions. At his show this spring at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, for example, he set up a room where an assistant screenprinted white T-shirts with his signature terse, block-print headlines, ranging in tone from vaguely political (LESS OIL MORE COURAGE) to hospitably absurd (I HAVE DOUGHNUTS AT HOME). They cost $20 apiece.

Ah yes, the t-shirts. Not sure if I ended up being the only one, but I was apparently the first to order a complete set of all 24 shirts. So there’s that.

I have been an admirer and follower of Rirkrit’s work since his earliest shows at Gavin’s, and Untitled (Playtime), the awesome, ply&plexi, kid-sized replica of Philip Johnson’s Glass House he built in MoMA’s sculpture garden in 1997 [above] bought him at least a decade of good karma in my book.

And so it’s only very recently that I’ve started to watch and wonder if I’m the only one who– See, this is why Faye Hirsch’s quote is so perfect: because it encapsulates exactly how people talk and write and think about Rirkrit’s work, and it’s perfectly and exactly wrong.

I’m sorry, that’s the overdramatic hook in this post. What I really mean is, as his social, experiential, ephemeral practice, his “art without objects” has taken off, Rirkrit has also been making some of the blingiest, sexy-shiniest, most ridiculously commodified luxury objects around. I love them. Why can we not talk about them more?

Untitled (Apron with a Thai Pork Sausage), 1993 via

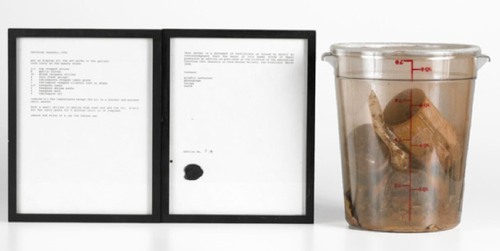

Hirsch is right in one sense, or at one time: early on, Tiravanija’s objects used to be slight, and leftovers and dirty dishes were common. A couple of pieces in Rago’s upcoming sale give a taste: one’s a butcher paper apron with a sausage sticker, above; the other’s a framed recipe and a cup of empty cans, below,

Untitled (Beauty), 1994, via

which came from a ramshackle kitchen-in-the-gallery show at Jack Hanley in San Francisco.

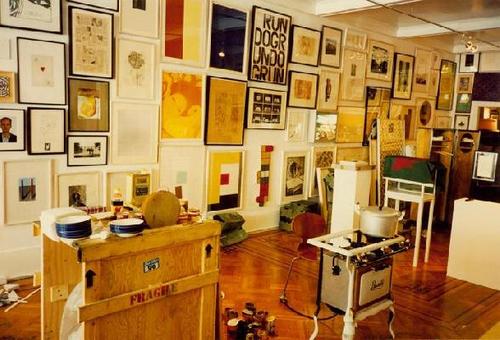

Untitled (Beauty), 1994, installation view, via jackhanley.com

The first Rirkrit piece I didn’t buy was a tent with a little video of Parisian skateboarders projected inside. It had more presence than the plexi vitrine filled with discarded mussel shells, and looked more serious than the Japanese plastic display ramen, but all the objects really did seem to reinforce the sense that the “essence of his work resided” elsewhere.

Substantial [re]built structures–like his apartment at GBE/Passerby, and the caravan he drove across the US on a pilgrimage/project to visit Earth Art works–felt provisional and disposable because they were plywood. But that scruffiness, of course, didn’t stop MUSAC from buying it.

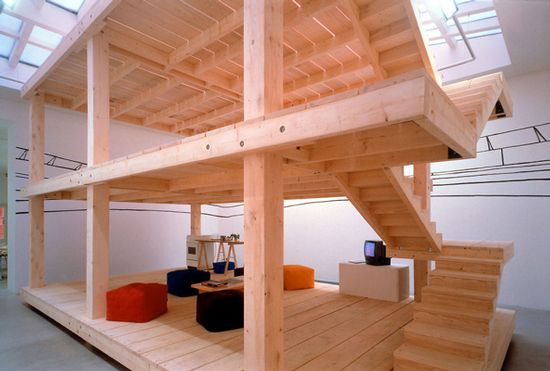

Dom-Ino, 1998, via: crousel

Something seems to have happened between 1998, when he showed Dom-Ino [above], a beautiful, but simple timber replica of a Le Corbusier structure at Crousel in Paris; followed by the plywood apartment, Untitled (tomorrow can shut up and Go away), in 1999 in New York and his 2002 show at Secession. Because though he was still recreating historically resonant architecture, Vienna was a spectacular blowout.

untitled 2002 (he promised), 2002, via guggenheim

Untitled 2002 (he promised) was a full-scale model of a section of RM Schindler’s Kings Road House, plus the garden, all executed in mirror-like stainless steel. It was designed to host music, films, and Thai massages. Reviewing the show for Frieze, Mathias Dusini made one of the early, obvious, and soon-to-be-rare invocations of this incredible object:

Since he surfaced on the art scene ten years ago Tiravanija has developed a hippyish critique of participation in art, in which he encourages people to drink tea together, watch films or knit. After the vernissage-grillage was over, however, it was evident that Tiravanija is neither a one-man health centre nor a catering company chef but a sculptor who knows how to combine art-historical references with specifically situated ideological models.

After the feast, when the room was empty of visitors, it became clear that a backdrop of mirror-like metal was all there was to see.

Ah, not quite. Because in the mirror-like metal, what we actually see is ourselves. So though the cynic might be tempted to tie the increased production value to fame-driven exhibition budgets, the materials upgrade also reinforces awareness of the works’ specific objective: the audience’s social interaction in the structure.

That modernist revival looks sexy as hell in chrome is just a market-friendly coincidence. In the 00s, Rirkrit’s market had caught up with him, and vice versa; shiny iconic, utopian pavilions that have done their experiential duty proliferated along with pavilion collectors. Just because it can’t fit in your apartment doesn’t mean it’s not collectable.

The Guggenheim acquired Untitled (he promised) in 2004. This insane Tea House is from 2005, I think.

Palm Pavilion, 2006-8, being installed at Inhotim, via Daniela Name’s flickr

After debuting at the Sao Paulo Biennial in 2006 as a film screening room, Palm Pavilion, Rirkrit’s silvery reconstruction of Jean Prouve’s Maison Tropicale, eventually ended up in the world’s biggest pavilion collection, Inhotim.

En route, it also appeared at the artist’s Mexico City gallery, kurimanzutto, where it was installed alongside–come to papa!–a set of Rirkrit-modded, Enzo Mari autoprogettazione patio furniture.

I’ve been smitten by Rirkrit’s Mari mashups ever since I first saw the stainless steel set at Basel in 2004.

Huh, whaddyaknow, I wrote about Rirkrit’s sexy, dematerialized-looking objects as such 2.5 years ago now. 2004 may have been when the chrome really kicked in, and not just for pavilions, but at all [sic] price points.

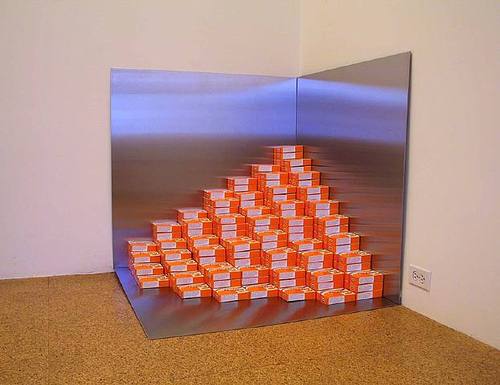

That’s the date for Untitled (Cooking Corner), the earliest piece I’ve seen where Rirkrit riffs on Robert Smithson’s iconic three-mirrors-in-a-corner non-site sculptures. And these are sculptures, not sets or props for a social experience. And they’re certainly not free. The beauty of these–besides their obvious aesthetic appeal, that is–is that just like the modernist architecture and design, Smithson was enjoying his own revival in the 00’s, but there’s precious little work to be had at any price. So Rirkrit’s mirrored corner pieces deliver that sweet, Smithsonian look, while his anti-materialist, art historical criticality or whatever helps ease collectors over the too-referential hump. These would not work, I think, without the relational practice, even though I’m kind of stumped what, if anything, they have to do with it.

[FWIW, Untitled (Cooking Corner) was bought by Tim Nye, shown by Tim Nye, and is now being sold by Tim Nye. A $40-60,000 estimate doesn’t seem crazy; it’s probably only 2-3x the original price. My fascination with Rirkrit’s objects is not that they’re overhyped market darlings, but that they exist at all. And are so patently seductive.]

that outlet is so unprecious: Untitled (Social Pudding Corner), 2004, image via 1301PE/artnet

Ah, maybe this piece, Untitled (Social Pudding Corner) is the earliest. Rirkrit and SUPERFLEX did a joint show at 1301PE in LA at the end of 2003 that contemplated trading the concept of “the fabric of society” for “the pudding of society.” The thread continued with Superflex’s reappropriation for Guarana Power Corner, 2006, and Rirkrit’s Untitled (let them eat mussels), 2007.

Untitled (let them eat mussels), 2007, image via covers & citations

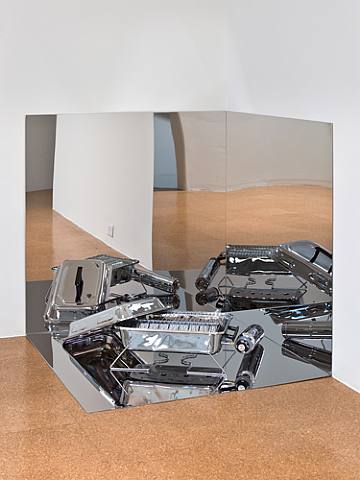

The mirrored surface almost swallows itself by 2010, the date for Untitled (BBQ), also at 1301PE.

Untitled (BBQ), 2010, images via 1301PE

I guess the reference to Smithson can make sense if you apply the site/non-site dyad to Rirkrit’s social practice; things like rice steamers and BBQ’s and mussel shells are the cookout equivalents of Smithson’s transferred coral and sand piles.

Except, is that Rirkrit stunt-cooking inside Untitled (BBQ)? I believe it is. So the site/non-site, cook/non-cook, experience/memory, action/object pairing doesn’t hold after all? Or is this how he authenticates/inaugurates the objects; they still have to be used? I want to hold these seemingly contradictory concepts in my head at once, I really do!

You know what did me in, though? Pushed me over the edge, without quashing my desire for these things? It was not Untitled (family of four), 2006, the mirrored stainless steel pedestal covered with a mound of rice grains cast in sterling silver.

And it was not the otherwise awesome Belgian collectors, the Gordts-Vanthournouts, who told The Art Newspaper Basel Daily edition [pdf] that they “only bought it on condition that the gallery [kurimanzutto] will do the silver-polishing themselves. We agreed to post the rice back to Mexico so it can be polished by local Mexicans. It’s included in the price.”

It was not the teak le Corbusier t-shirt pavilion barge.

It was the ping pong table. The #$*(%ing sick, mirrored steel, $50,000 ping pong table.

I mean, yeah, the boy’s club playing ping pong in Nyehaus was obnoxious, as was the NADA Miami Beach lawn pong install, but that’s not the problem. The problem, bless Cumulus Studio’s heart, is that it’s being sold as “outdoor functional objects by contemporary artists.” I’ve been soaking in the art/artist furniture, art/non-art soup for a very long time. I’m typing this on my Mari X Ikea table, which will be an art object the second I put it in a gallery [which, email me, we’ll talk].

But with this ping-pong table, you can pretend it is not a ping pong table, but is actually a sculpture. Except that it’s being sold in an edition of 10 by a lawn furniture dealer. Somehow this seems non-trivial. It feels like product.

And yet, all along, Rirkrit has produced some proper editions with Klosterfelde which have a distinctly humble, documentary utility that feels closer to the “true,” Tiravanija-ism, the only one critics and curators talk about. That flashy stuff is flashy, but these tent-jackets and bike-showers are good for you.

And yet, shiny objects are so irresistible. Which makes this Untitled (solar cooker), 2007, of the most nuanced objects Rirkrit has made. My understanding is it was a fundraising edition [of 10, no sweat] for the land, his long-running collaborative site in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Yes, it’s mirrored shiny, but it’s found mirror, an actual solar oven, complete with rice pot and some the land rice. Even if the the land logo is a little SUPERFLEX SLICK, this feels very real and tight to me. Do want.

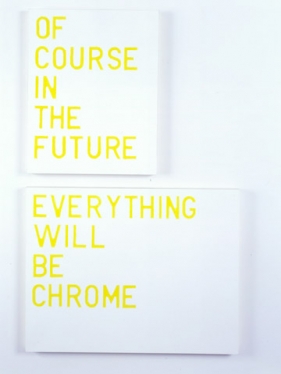

Somehow I go this long and I still don’t mention the neon pieces or the paintings. Here’s one. It feels important, foundational, even, even if it’s taken from a Spongebob Squarepants episode: Untitled (of course in the future will be chrome), 2003. [image via nyehaus]

Which is kind of funny, because as the artifact corner pieces and MoMA’s acquisition of the 2007 redo of the 1994 curry piece betray, Rirkrit’s objects are often vestiges of the previous experiential pieces. At his show this year, he recreated Gavin’s first space [out of plywood] and filled it with silver-glazed ceramic replicas of all the objects he showed/used in his first show. Untitled (558 broome st, the future is chrome). And so, now, is the past.