I’ve been writing this post in my head for months, years, even, but so many pieces have piled up in my browser tabs, it’s slowing my computer down. And plus, this weekend MoMA announced that they acquired and will exhibit Untitled (Free/Still), the original [sic] free-Thai-curry-in-a-gallery work, so it’s time to step back and look more closely at Rirkrit Tiravanija’s art practice. First, by starting with what we are fed. Here is a small sampling platter of familiar statements by and about the artist and his work:

“It’s part of what has been called ‘relational aesthetics,’ ” said Ann Temkin, chief curator in MoMA’s department of painting and sculpture. “Joseph Beuys created social sculpture; it’s the act of doing things together, where you, the viewer, can be part of the experience.”

That’s from MoMA’s press release in the NY Times.

You could say his art is all about building “chaotic structures.” Then again, it’s about lots of things; his work is so open-ended and departs so radically from the art market’s orientation toward precious objects, that it’s earned many labels, many – like utopian or chaotic – that only tell part of the story. But one that’s stuck, for better or worse, is French theorist-critic Nicholas Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics,” the idea of judging the social relationships sparked by an artwork instead of merely considering the object.

That’s Paul Schmelzer, now/again of the Walker Art Center, an early and frequent supporter of Rikrit’s work, writing in 2006.

Tiravanija’s art is free. You only need the experience. In fact, the essence of his work resides in the community, their interrelationships, and chance. Make art without objects, their purpose is a complaint against the possession and accumulation.

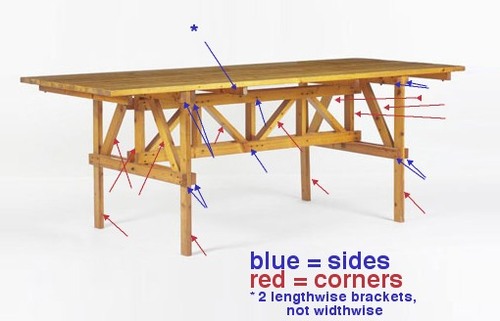

The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, which owns Untitled (Caravan), a 1999 plywood model of a camping trailer, with kitchen, above.

Rirkrit as quoted by Bruce Hainley in Artforum, 1996:

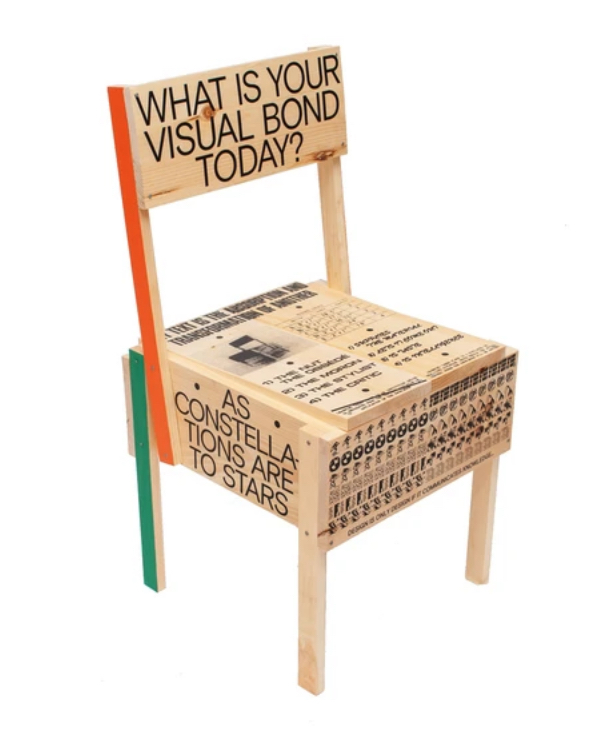

“Basically I started to make things so that people would have to use them,” he has said, “which means if you [collectors, museum curators, anyone in these roles] want to buy something then you have to use it. . . . It’s not meant to be put out with other sculpture or like another relic and looked at, but you have to use it. I found that was the best solution to my contradiction in terms of making things and not making things. Or trying to make less things, but more useful things or more useful relationships. My feeling has always been that everyone makes a work – including the people who . . . re-use it. When I say re-use it, I just mean use it. You don’t have to make it look exactly how it was. It’s more a matter of spirit.”

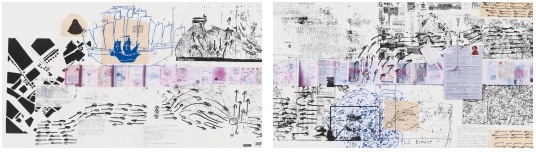

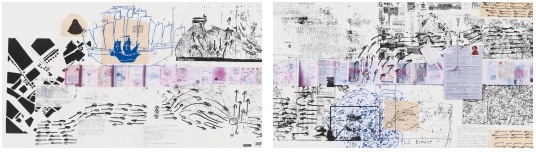

And here’s Faye Hirsch in Art in America this summer, perfectly teeing up her making-of story for Untitled (the map of the land of feeling), [above] an extraordinary 84-foot-long print edition Rirkrit has worked on for the last three years with students and staff at Columbia’s Leroy Neiman Center for Print Studies:

Rirkrit Tiravanija has never been known as a maker of elaborate objects. In a market-riven art world, he has remained, since the early ’90s, a steadfast conceptualist whose immaterial projects, enmeshing daily life and creative practice, have earned him a key role in the development of relational art. At galleries and museums around the world, he has prepared meals and fed visitors, broadcast live radio programs, installed social spaces for instruction and discussion, set up apartments–where he or visitors might live for the duration of a show–and dismantled doors and windows, leaning them against walls. At two of the three venues for his 2004 retrospective, the “display” consisted of a sequence of empty rooms referencing (in their proportions and an accompanying audio) his selected exhibitions over the years.

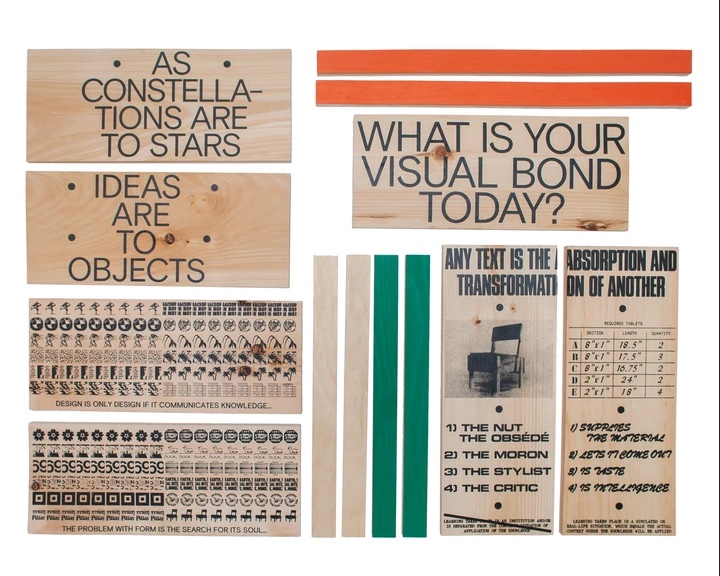

When Tiravanija does make objects, they are generally of a modest nature–most often multiples and ephemera connected with exhibitions. At his show this spring at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, for example, he set up a room where an assistant screenprinted white T-shirts with his signature terse, block-print headlines, ranging in tone from vaguely political (LESS OIL MORE COURAGE) to hospitably absurd (I HAVE DOUGHNUTS AT HOME). They cost $20 apiece.

Ah yes, the t-shirts. Not sure if I ended up being the only one, but I was apparently the first to order a complete set of all 24 shirts. So there’s that.

I have been an admirer and follower of Rirkrit’s work since his earliest shows at Gavin’s, and Untitled (Playtime), the awesome, ply&plexi, kid-sized replica of Philip Johnson’s Glass House he built in MoMA’s sculpture garden in 1997 [above] bought him at least a decade of good karma in my book.

And so it’s only very recently that I’ve started to watch and wonder if I’m the only one who– See, this is why Faye Hirsch’s quote is so perfect: because it encapsulates exactly how people talk and write and think about Rirkrit’s work, and it’s perfectly and exactly wrong.

I’m sorry, that’s the overdramatic hook in this post. What I really mean is, as his social, experiential, ephemeral practice, his “art without objects” has taken off, Rirkrit has also been making some of the blingiest, sexy-shiniest, most ridiculously commodified luxury objects around. I love them. Why can we not talk about them more?

Continue reading “Transactional Aesthetics, Or The Highly Collectable Rirkrit Tiravanija”