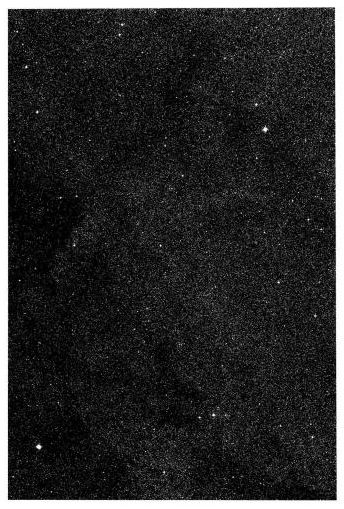

From around 1989-92, the German photographer Thomas Ruff created a body of work using astronomical survey photos from the European Southern Observatory in Chile. There is very little discussion online of this series[1], even though I believe it's the first time Ruff uses a found image in his work. [Before the Sterne series, Ruff was known for his very large portraits of his friends, which he described as "a construct based on identification photographs." Since then, he has appropriated and manipulated many types of photos, including industrial catalogue illustrations and internet porn.]

Ruff talked briefly about the Star photos in a rather painful 1993 interview with Philip Pocock:

Pocock: Why stars? Do they mean something extra special to you?

Ruff: When I was eighteen I had to decide whether to become an astronomer or a photographer. I also wanted to move the so-called künstlerische Fotografie boundary. Do you know Flusser?

Pocock: No.

Ruff: He defines isolated categories for photography that sometimes cross over. For example, if medical photography is used in a journalistic way, or with the Stars, a scientific archive isn't used for scientific research but for my idea of what stars look like. It's also a homage to Karl Bloßfeldt. In the twenties he took photographs of plants to explain to his students architectural archetypes. So he was a researcher but the way he represented his intention with the help of photography made him an artist. I like these crossovers.

All interesting enough, but given the photos he uses, I think the most relevant perspective comes earlier in another part of the interview, where he distinguishes between photographing to "capture reality" and "to make a picture."

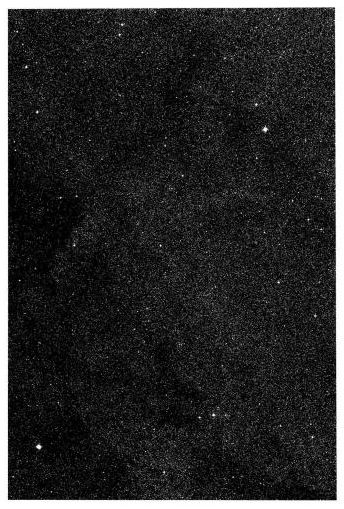

Ruff definitely makes an awesome picture. The Sterne photos are stunning, at least the largest prints--185cm wide by 250cm tall--are. They generally do well at auction, though it sometimes feels like the ones that do better are the "starrier" ones, a notion that seems to play right into Ruff's interest, inherited from his teachers, Berndt and Hilla Becher, that photographs are cliches, constructs of expectations ["my idea of what stars look like," even.]

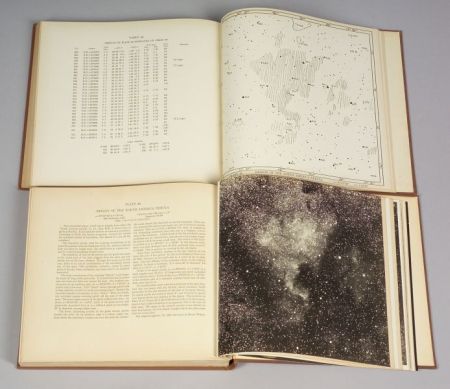

The photos Ruff used came from a project so conceptually ambitious and subjectively constrained, it'd do the Bechers proud. The ESO Southern Sky Atlas was a massive undertaking, an attempt begun in 1972 [images were taken from 1974-1987] to document the entire visible universe. Or at least the half of it visible from the Southern Hemisphere. And just the objects of enough magnitude to show up with the then-new 100-inch UK Schmidt Telescope and the 1m ESO telescope at La Cilla, Chile. And which could be seen on Kodak's then-new, experimental, hypersensitized emulsion.

The resulting 1,000+ photos are at once evidence of photography's futile limitations, and one of its greatest artistic achievements; they out-Becher the Bechers. The Sky Atlas is just one of several sky surveys over the 20th century. Each starts out with the same ambitious goal; each takes years of painstaking work; each results in images and objects that exhibit conceptual rigor and contemporary visual appeal in equal amounts; and as technology progresses, each is rendered utterly obsolete by the next survey. Particularly as astronomical data is digitized, the era of producing objects--glass negative plates and photographic prints--has died. Now it sits, at best, forgotten and neglected in university libraries and on storeroom shelves. At worst, it will be cleared out and dumped, replaced--people think--by a small stack of CD-ROMs or a web server.

For such projects, once-scientific milestones that represent an era's pinnacle of our achievement, the literal attainment of the capacity of human vision, maybe the best thing for them is to stop being science and start being art.

Note to astronomical librarians: if you're clearing out old sky surveys and atlases, please dump them my way.

[1] At least in English. Henning Engelke wrote about the Sterne series and the science-to-art spectrum, but it's in German and locked in a in pdf. maybe this google translation of the reformatted html version will be comprehensible.