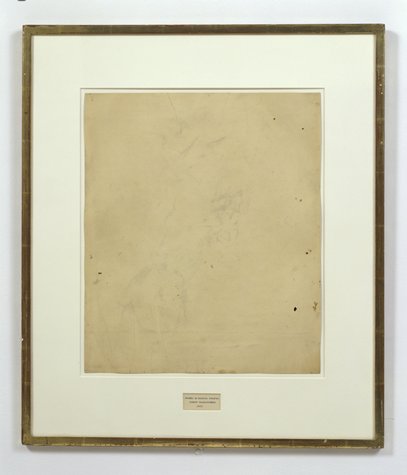

Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, "drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame." via SFMOMA

TIMELY BUT UNNECESSARY HOOK: LAST VISIT TO THE DE KOONING RETROSPECTIVE

Part of the reason I hustled back to MoMA Sunday was to look through the de Kooning retrospective from the perspective of his relationship to other artists [or really, vice versa].

Last summer, while mapping out the history of the reception of Robert Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing, I thought Leo Steinberg got it the rightest when he called the work "a sort of collaboration" which treats erasure as generative, not destructive. And sure enough, de Kooning's drawings and paintings of the 50s are filled with erasures, and smudges, and obliterations; they're accepted as legitimate markmaking strategies. Which could make Rauschenberg's project an extension or variation on de Kooning, not a patricidal, rebellious break, as it's come down to us. There's a continuity and dialogue right in front of us which we are not-told to ignore.

But while I'm glad to give attention to what I think are Steinberg's and Tom Hess's persuasive arguments about the deK/RR affinity, I don't really have much to add to them.

MUCH OF WHAT WAS KNOWN AND THEN SAID ABOUT ERASED DE KOONING DRAWING TURNS OUT TO BE DIFFERENT OR YES, WRONG

What I'm still trying to pin down are the basics of Erased de Kooning Drawing's history. Because it's become very clear that it has been presented and interpreted differently over time. It was not even exhibited until 10 years after it was made. Many prominent critics, especially those who considered it an ur-Conceptual masterpiece, seemingly wrote about it without seeing it. For decades, Rauschenberg claimed and everyone assumed, that he had created the work alone, but in 1999, when he gave EdeKD to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he revealed that Jasper Johns had given the work its title and had hand-drawn the "label." And it turns out that Rauschenberg physically altered the work over the years, after exhibiting it at least twice, in ways that have never been addressed.

The Erased de Kooning Drawing we know is not just a drawing. According to SFMOMA's complete description, it is comprised of "traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame." To get the point across clearly, Rauschenberg wrote, "FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING" [all caps and underlining in the original] on the paper backing.

But in Emile de Antonio's 1970 film, Painters Painting, Erased de Kooning Drawing appears unframed and unmatted. The sheet with de Kooning's original drawing is mounted on a longer piece of paper on which Johns [it turns out] drew the precise, label-like box of text.

Now I think the way it appeared in Painters Painting is how the artist meant for it to be seen. The earliest exhibition sticker on the back of EdeKD is from 1973. Which made me wonder if the work had even been shown before then. Finally, I found out. Yes. At least twice.

DO WE EVER CALL EDEKD PROTO-MINIMALIST?

In January 1964, Samuel Wagstaff organized "Black, White + Gray" at the Wadsworth Atheneum. The "Zeitgeist show," to use James Meyer's term, came to be considered the first museum exhibition of "minimalism," and Wagstaff specifically asked Rauschenberg to provide "works that have no color...the sparser the better."

WERE THERE EVER PHOTOS OR REPRODUCTIONS OF IT BEFORE 1976?

According to the exhibition checklist, Rauschenberg loaned exactly what the title called for: a black painting, a white painting, and a relatively gray work, Erased de Kooning Drawing. The registrar's record [graciously investigated by Atheneum assistant archivist Ann Brandwein] indicates the work was unframed and unmatted, and that it measured 12x18 inches. [It was also valued at $1,200, but listed as "not for sale."] There was no catalogue for the 4-week show [Jan 9 - Feb 9], and EdKD doesn't appear in the few installation photos that survive.

But the piece did get noticed. In her review for The Hartford Times critic Florence Berkman wrote:

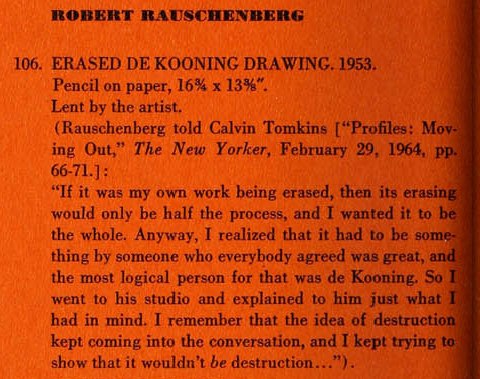

Perhaps the most unusual work is one called "Erased Drawing" [hmm] in which two leading artists, Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg are involved." Mr. Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning drawing, leaving enough of the design so that it can be seen in a strong light.And soon after the Wadsworth show closed, on Feb. 29, 1964, Calvin Tomkins' first long profile of Rauschenberg appeared in the New Yorker. It included the artist's first published discussion of EdeKD. When Lawrence Alloway showed the work in his American Drawings survey at the Guggenheim that fall, he included the paragraph from Tomkins' article in the catalogue checklist, the only piece to warrant [or maybe to require] an explanation:

American Drawings catalogue, p. 60, Sept 1964, curated by Lawrence Alloway via guggenheim.org

Of course, just a couple of months after I chased down and bought my own copy of the catalogue, the Guggenheim released an electronic version on their website.

The dimensions here are slightly different--16 3/4 x 13 3/8 inches--but the medium is the same: "pencil on paper." Whatever their internal variations, though, the drawing's 1965 dimensions differ significantly from its current, frame-like object state, which SFMOMA lists as 25.25 x 21.75 x 0.5 inches. Here's a handy, pixels-per-inch graphic to show the relative sizes.

However it was perceived before the early 1970s, whether as patricidal Dadaist prank or Minimalist forebear, Erased de Kooning Drawing came to be seen as an uncannily prescient, process-oriented, Conceptual object. But that's not just because the art world finally caught up with Rauschenberg, 20 years later. It's because Rauschenberg himself reconceived and transformed the work in the wake of, or in response to, Conceptual Art.