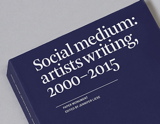

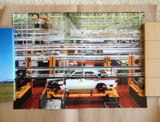

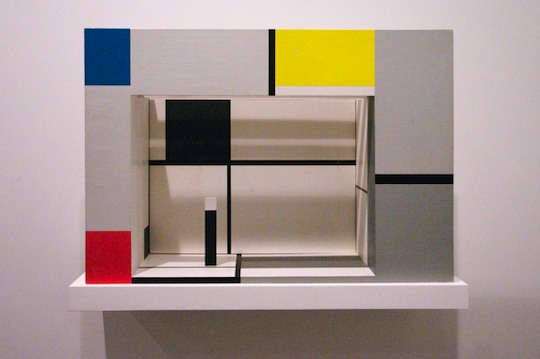

Model for set design, "L'Ephemere est eternel," 1926, recreated in 1964, photographed in 2008 at Vanabbemuseum by Jeff Werner

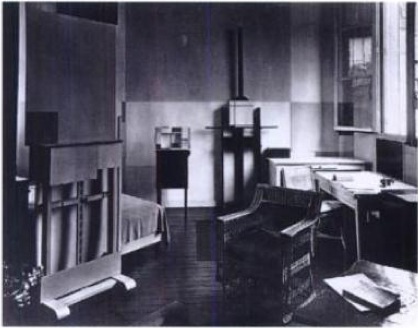

After reading Michel Seuphor's Dada play "L'Ephemere est eternel" in 1926, Piet Mondrian surprised his friend by designing sets for each of the three acts. The little models were photographed amidst Mondrian's paintings in his studio, a nice parallel to the play's denouement, in which a model of a theater is destroyed by an executioner. It also resonates with a play Mondrian himself wrote in 1919, which ends in his studio. For someone trying to change all the world, the stage was a nice place for a dry run.

Susanne Deicher noted that Mondrian refused to be photographed painting in his studio.

Mondrian often said that "new life" could be found in the free space opened up by reason and thought. The empty plane at the centre of the small painting on the easel reflects the absence of the artist.This absence to Mondrian's ideas for the staging of "L'Ephemere" as well. He really wanted sets that concealed the actors as they delivered their lines. To what extent Seuphor was on board with Mondrian's creative involvement, I don't know.

During this period Mondrian frequently spoke of the end of the subject in the new age to come. He designed his studio as an imaginary setting for a theory without an author, where the "new" appears to evolve in the non-space of the empty center of his abstract paintings.

I also don't know in what form it circulated at the time, or how widely it was read or known, but Seuphor's play was not actually ever performed until 1968. By then Mondrian's original models had been lost; someone--perhaps Seuphor himself--had refabricated one in 1964. It's in the collection of the Vanabbemuseum in Eindhoven. [That's where Vancouver designer/blogger Jeff Werner photographed it in 2008.. I first saw it a few months ago in "Inventing Abstraction" at MoMA.]

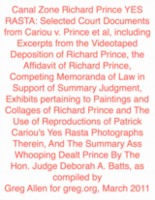

Remarkably, the US premiere of "L'Ephemere est eternel" took place in 1982, at the Hirshhorn Museum. It was one of several ambitious elements of Judith Zilczer's exhibition, "de Stijl: Visions of Utopia: 1917-1931." The show also included a large-scale recreation of Theo van Doesburg's lost interior of the cinema/cafe in the Aubette in Strasbourg. The opening was attended by Queen Beatrix, who, on a state visit, discussed nuclear proliferation and anti-NATO protests with Ronald Reagan.

Georgetown University theater professor Donn B. Murphy directed his and Zilczer's 60-minute adaptation of Seuphor's absurdist, plotless, and wordplay-filled script, which ran for at least seven public performances during the weekend of June 25-27. The show was in the museum's auditorium, which barely has a stage, more of a podium, but which was apparently able to accommodate a full-scale version of Mondrian's spare, shallow set.

The Washington Post hated it. In his review David Richards summed up the play's Dadaist, traumatized historical context as "the intellectual's version of 'Hellzapoppin,' music-hall for the nihilists born of World War I." Which, well, I guess it could be worse. Whatever could Dada tell the world of Washington during the throes of the Culture and Cold Wars and at the onset of the AIDS pandemic? [On the same page, the Post hated on John Carpenter's remake of The Thing, starring Kurt Russell, even more.]

In the Dada spirit of non sequitur, and to add one more datapoint to calibrate the Post's critical settings, I can't not quote from the their review of a local stand-up performance by one Jay Leno:

Leno's nasal delivery, which resembled Andy Rooney's, expanded to a colorful palette of characters as he worked through subject matter including the Phil Donahue show, photo stores ("How come they can transmit pictures 80,000 miles through space, and you walk across the street to Fotomat and they can't find yours?"), male strip shows, Steven Spielberg movies, video games, and even local deejay Howard Stern.Anyway, the Hirshhorn has a [VHS!] videotape of the performance in their archive. I will be making my appointment pronto.