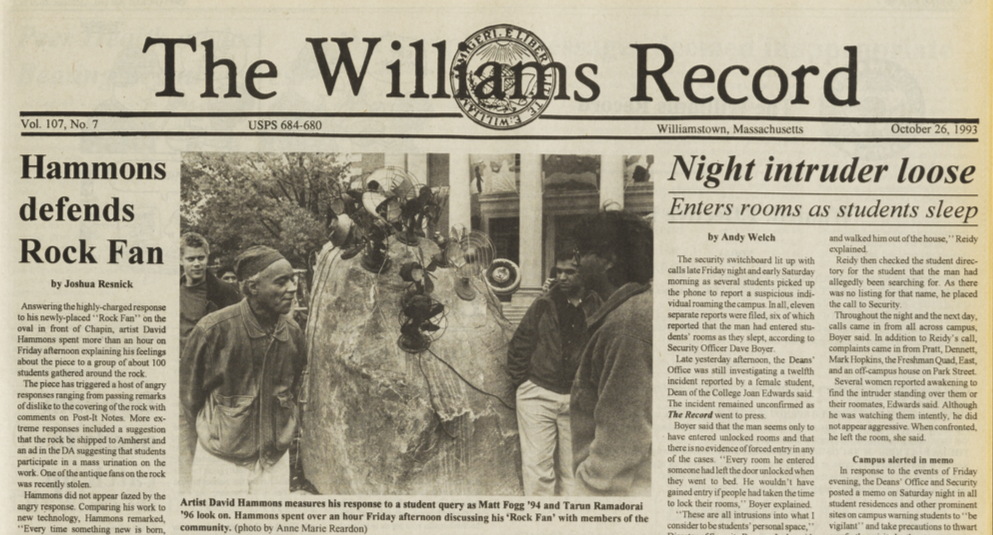

Four years later, Hammons again encountered local resistance while installing another outdoor sculpture, which was then vandalized, and later destroyed. It all went down on the bucolic campus of Williams College, in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

In October 1993 Hammons opened a show, curated by Deborah Rothschild, at the Williams College Museum of Art. Yardbird Suite, the indoor installation of boomboxes in trees playing Jazz was chill. The six-ton boulder placed in front Chapin Hall at the center of campus, with antique fans bolted to the top, was not.

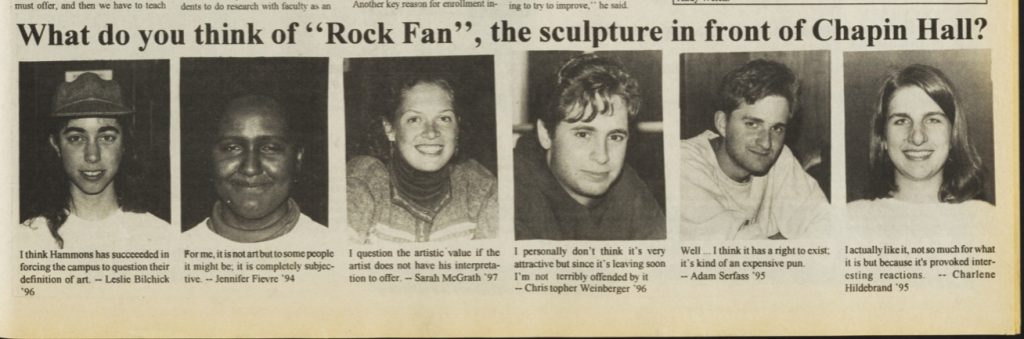

Students began questioning and criticizing the piece as Hammons was installing it. He called it Rock Fan, which only seemed to incense those demanding deeper meaning or significance from this work of art temporarily in their midst. [He also told some agitated students that it was called The Agitator.] In Williams’ hyper-privileged and hyper-collegial culture, every gifted scholar was expected to be able to weigh in on everything. In practice, this meant students commented on Post-It notes on literally whatever poster, building, vending machine, or public sculpture they encountered.

They criticized the site, the title, the fabrication, the aesthetics, the imagined expense, and the disruption. Some complaints were reported in the weekly student paper, The Williams Record. Additional back and forth took place a daily student bulletin, plus the Post-Its. While he was on site, Hammons gave as good as he got.

“You don’t have to make it into some big mystery. Damn, relax. Use your energy on something else besides intellectual masturbation,” he said.

…

Hammons added that he was primarily interested in confronting and challenging people with images that they aren’t used to seeing or which seem out of place. “I’m in the business of making the invisible visible…Most of your eyes are very weak, so you need to see things you’re not accustomed to seeing so that your eyes get much stronger.” [WR 10/26/93]

In the first couple of weeks, a student or students [I haven’t been able to find yet] surrounded Rock Fan with their own sculptural responses: accordion-folded paper fans glued to small rocks [top]. Then came the painters, dousing Rock Fan with purple paint for Homecoming.

On March 3rd, 1994, David Hammons gave a slide lecture at SFMOMA, introduced by curator Gary Garrels, which ends with Rock Fan[s]:

And this is a piece at Williams College called Rock Fans.

This was protested. For about the last five months, they’ve been protesting this piece on their campus. And so some students made fans out of paper and put these little rock fans around the piece. It’s been vandalized and written about.

When the wind blows, the fans actually move. Someone said, “I don’t care how many fans you put on it, it’s not going to fly.”

And this is after Williams students painted the rock. Someone called me and told me that now they feel like it’s theirs, because they painted it their school colors.

The transcript of the lecture–but not the slides–was published this year by the CCA Wattis Institute as part of their year-long program devoted to Hammons and his work. The book, David Hammons Is On Our Mind, was created in collaboration with the artist. There are photos he selected, a poem by Tongo Eisen-Martin, and a text by Fred Moten. Reading Hammons’ narration of invisible slides creates an exquisitely baffling disjuncture that has to be intentional. It definitely sent me looking for things I was not accustomed to seeing.

Rock Fan was originally meant to travel to SFMOMA, too, but at some point Hammons decided it would not. He left it at Williams; it was removed in April, during Spring Break. The fans went back to the artist. I haven’t found the rock.

In 1997 Hammons appropriated the Williams students’ response to his sculpture to make a new Rock Fan out of a stone and pleated fabric. In 2004 the director of the Williams Museum found out about it at Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn’s place, and acquired it for the collection. In 2012 Robbi Behr (’97) designed a Rock Fan-themed coffee mug for their 15th reunion.

Previously, related:

How ya like How ya like me now?

Public Enemies Nos. 2–?

Stop and Piss

‘Art objects are tailored for physical spaces owned or controlled by the social elite.’ Will I never be able to stop returning to this 1995 Frieze essay on signifyin’? That is fine with me.

Jordan Stein found some amazing stuff on attempts to restore/repair/remake Philip Johnson’s little Giacometti