I guess it doesn’t matter anymore that I don’t see why the White House’s art borrowing is news now, when almost the entire list was already published and discussed four months ago [and many weeks before that, too].

Because now some wingnut Know-Nothings have taken it upon themselves to accuse Alma Thomas of plagiarizing Henri Matisse, an act which reinforces their hard-held disdain for the Obamas and anyone and anything associated with them.

It’s a false and defamatory claim, and the real story of Thomas and Matisse is deeply fascinating and diametrically opposed to the spiteful, divisive worldview in which it originated. But it didn’t seem that useful to just say so.

So I went ahead and read all 200 or so comments on the Free Republic thread where the controversy was born to see if they figured out on their own that Thomas’s 1963 painting, Watusi (Hard Edge) [top] was originally created as a deliberate reworking of Matisse’s large 1953 cutout collage, l’Escargot [above], and that it had always been recognized and discussed as such by the people who followed Thomas’s work.

By around comment #120, they’d at least decided that it was “a study,” and that Thomas wasn’t a fraud, just a hack. So a small victory for fact buried under an inflammatory and inaccurate headline.

As a hopeless art elitist and documented Obama campaign donor, there’s obviously nothing I could ever say that would persuade a hater that the Obamas’ choices of art do not, in fact, catch them out as uppity, ignorant, race-hating, affirmative actionist, communist, stalinist, Nazi frauds or whatever.

Look under the hood, though, and the substance of the angry right’s criticism of Thomas–and, often enough, frankly, of Matisse–sounds very familiar: specifically, the perceived lack of skill involved in making “modern” art; and Thomas’s lack of originality, or more precisely, the rejection of appropriation as a valid artistic strategy.

Here are some representative comments from the Freepers. First up, the “My child could do that” critique:

kudos. that also looks like something my kids made in grad school. 😉

Grad school? You paid to have them do that??

grade school i meant, not grad school

With a little guidance, a four-year-old could make “art” like that.

Here is the Matisse:

My kids used to make those too.

when my kids were little and i volunteered in the chandler school district (also taught) we made stuff like this in K-2 grade. tear the construction paper and glue.

I always thought that the later Matisse was something of a fraud and and a hack, btw.

Which dovetails nicely with both the reality of the Matisse and the technique. L’Escargot was made just a year before the artist’s death at 84, and 12 years after his age and failing health left him unable to paint. He saw the cutout and collage technique as means to “get a more powerful expression of pure color through the sharpness of the outline.” If kids are learning color and composition in school today by making cutouts and collages, it’s because of Matisse’s influence.

As for the originality complaint:

Great work. I left a message for Carol Vogel and told her she needs to write a follow up story that the work of art is a ripoff on Matisse.

The least we can do is blackball her work from the WH.

Silly rabbit. They’ll just claim that Matisse stole it from Thomas.

Cheap tricks are a hallmark of today’s collegiate education.

Just like the President, a pale imitation of the real thing.

Basically, it was an admitted study of Matisse. Probably not as big if a deal as is what first appears.

I don’t believe it was a “study” of Matisse. More like a rip-off.

Clearly a ripoff. Maybe it should be titled “An Homage To A Better Artist Than I.”

They’re righter than they knew. Thomas had seen l’Escargot at The Museum of Modern Art in 1961. According to art historian Ann Gibson’s essay in the catalogue for Thomas’s 1998 retrospective [ed note: not Corcoran curator Jonathan Binstock as I originally wrote], Thomas, who’d just retired at 70 and began painting full-time, took direct inspiration from the late work of Matisse, saying, “If an old, crippled-up man can do that, I can do it.”

Gibson also notes the audacity of a then-unknown painter appropriating directly from the last, most advanced, abstract work of one of the 20th century’s greatest artists. Her reworking of Matisse, he wrote, “was more than an implicit defiance of modernism’s creed of originality.” But one page later she backs off:

It’s important to note that while Thomas was appropriating, she was not making what has since come to be called “appropriation art.” Her main intention was probably not to deny originality as a value. But neither was she trying to hide her source–to fake.

Gibson doesn’t elaborate, and I’m not sure I’m convinced. I don’t mean that Thomas was some kind of pre-postmodern conceptualist Grandma Moses, but the making of Watusi (Hard Edge) definitely resonates far beyond the time and place it was created–and far beyond the early 1970s, when Thomas finally joined the national art discourse with her small, one-room show at the Whitney.

Thomas was the first graduate of Howard University’s art program and the first female African American MFA at Columbia, in 1934. Thomas began her career as an art teacher within Howard’s traditional, figurative aesthetic. Her embrace of abstraction came after she retired in 1960, and she set out to develop a modernist mode by studying the techniques and theories of leading artists from the US and Europe.

According to artist Jacob Kainen who she studied with in 1957, that included the “crutch” of color theory, from the Bauhaus through Matisse and others, and “paint[ing] a few tentative abstractions in which torn, rectangular shapes floated against troubled, light-filled backgrounds.”

So she studied Matisse’s forms, but not his technique [painting, not collage] at length. She took his composition–and turned it sideways. Then she took the great colorist’s colors–and replaced every single one with its near-exact opposite on the color wheel. Is this series of deliberate strategies not postmodern only because October hadn’t started publishing yet?

By 1963 and well into the 1970s when Thomas gained recognition as a black artist, there was a heated debate within her own DC art community about what “true” black art should be; figurative vs abstract/modern; Euro-American vs African. Thomas essentially rejected Africanism and took a stand for modernism and integration, even as she critiqued Matisse and other early modernists for borrowing liberally from African art.

[The Barnett-Aden Gallery, where Thomas hung out and showed in Washington, also showed work by Matisse, Picasso, and other leading modernists. For decades, it was one of the rare spots where the city’s black and white cultural communities overlapped and integrated. At a time when the Corcoran wouldn’t show work by black artists, Duncan Phillips would travel to New York for artseeing and buying trips with gallery owner–and Howard professor and Thomas mentor–James Herring. It sounds like the Obama’s kind of town.]

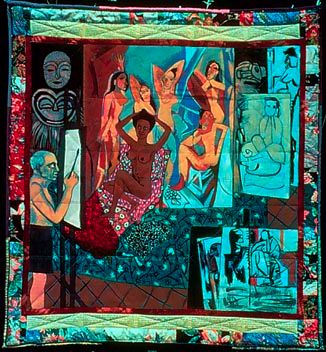

In an earlier essay on the “Avant-Garde” published in 1996, Gibson discusses Picasso’s Studio, a 1991 quilt-like painting by the African American artist Faith Ringgold, in terms that resonate directly with Thomas, Watusi, and Matisse.

Picasso’s Studio shows the artist, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and the “originals” he incorporated–“primitive” African masks–into his work which so decisively broke with the European painting tradition. Says Gibson:

Ringgold raises questions that strike at the heart of this aspect of the avant-garde enterprise: In the attempt to break away from the status quo, whose reversals are acceptable? Who benefits? And who decides?

[picking up further down]

Ringgold questions not only the the status that Picasso’s presumed originality granted to him as a representative of the avant-garde, but also the supporting role the art of colonialized nations and its feminine objects played in the avant-garde’s modernist enterprise.

Looking back, I have to wonder how it’s possible to say that Thomas, at least on her own terms, in her own context, and for herself, did not also directly challenge the “presupposition…that excellence was European and male”?

Watusi is hanging in the First Lady’s office. Another, later Thomas painting is installed in the foyer outside. Maybe the new burst off attention being paid to Thomas’s work will lead to a more expansive examination of our assumptions and interpretations of history–wingnuts and art worlders alike.