While researching the National Gallery of Art’s Barkley L. Hendricks paintings, which were purchased by J. Carter Brown with money from Michael Whitney Straight, I came across one of the crazier space-meets-art moments in the history of exhibition design: Art Fleet.

While researching the National Gallery of Art’s Barkley L. Hendricks paintings, which were purchased by J. Carter Brown with money from Michael Whitney Straight, I came across one of the crazier space-meets-art moments in the history of exhibition design: Art Fleet.

In an amusingly transparent move to manage his own complicated story, Straight wrote a biography of Nancy Hanks, the founding chairwoman of the National Endowment for the Arts, who had been appointed by Richard Nixon. [Straight himself had been approached to found the NEA by the Kennedy administration, at which point, he disclosed his history as a KGB spy. He became the deputy chairman, instead, a post which did not require Senate confirmation.]

Anyway, Art Fleet. We begin in San Clemente, 1970:

In the same spirit of loyalty to the president who had appointed her, Nancy committed the Endowment to supporting a project entitled Art Fleet. She had asked the president, when she met with him in San Clemente, what he would like the Arts Endowment to do. He had replied that “it was extremely important to get the arts out into the country.” Nancy had agreed. She was reminded of the technical problems involved in moving art masterpieces around the nation. She dismissed them. As Bill Lacy, our program for Architecture and Environmental Arts, recalls, “Nancy contended that if we could put a man on the moon, we could surely send the Mona Lisa around the country.” [p.149]

Surely, why not, but seriously, why?

And what do you want to do with the Mona Lisa again?

In explaining the rationale for Art Fleet, the NEA’s 1971 Annual Report [pdf] cited nationwide demand for high quality traveling exhibitions, which was being thwarted because museums faced prohibitive insurance costs.

But the reference to the Mona Lisa is not a coincidence. Margaret Leslie Davis’s 2009 book Mona Lisa in Camelot tells the fascinating story of how the current, official American arts landscape–from the blockbuster exhibition to the NEA itself–was shaped by Jackie Kennedy seducing Andre Malraux into loaning la Joconde in 1962. The NEA was clearly associated with Kennedy and his legacy. If Nixon wanted to co-opt or leverage that glow, it sounds like finding a way to repeat the Mona Lisa’s rapturous reception in NYC and Washington in cities full of people Nixon hated less, which was anywhere else.

In fact, the New York Times said in 1971 that Hanks was

reported to have said a year ago: “We could send the Mona Lisa to the moon and get her back without an extra crackle. Why can’t we send a John Singleton Copley from Boston to Los Angeles in perfect safety?”

Whoa.

Nancy commissioned two prominent design firms to prepare plans for a fleet of trailer trucks that would carry great paintings to every corner of our continent. A year’s hard work followed. Then in February 1971 a progress report was given to the National Council on the Arts. The briefing book prepared for the council stated: “As presently conceived, works of art would travel and be displayed in the same large containers. Each of these would be sealed from dust, their contents protected from vibration and shock under highly refined temperatures and humidity control.

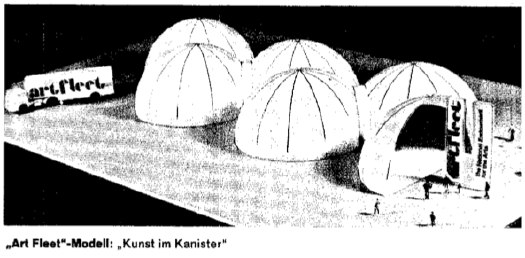

“Trailers would convey them. Inflated domes, interconnected, would shelter them. Exhibitions would be organized in units together composing a large show.”

Art Fleet seemed splendid on paper, as splendid as the stately pleasure dome which Kubla Khan in Xanadu decreed. In practice, the longer we worked on it, the greater its problems appeared to be. [ibid.]

Seriously, can I never escape inflated domes? Maybe it’d be easier to just ask everyone in the early 1970’s who didn’t have an art scheme involving inflatable domes to just raise their hands?

Art Fleet’s designers–George Nelson [!] and Charles Forberg, collaborating as Designers Associated–embraced the inflatable dome after visiting the Expo ’70 in Osaka, where pressurized domes were all the rage. I expect that a side trip to Lawson’s for a nikuman steamed pork bun was also an inspiration.

[Nelson had been invited to a design competition for the US Pavilion at Osaka; his proposal, a giant spaceframe structure, lost out to The Great Balloon, a 275-ft inflatable version of Buckminster Fuller’s ’67 pavilion, designed by [Ivan] Chermayeff & Geismar. That design was ultimately scrapped for budgetary reasons, and the “great bunion pad” was built instead.]

But it wasn’t just domes and trucks. Nelson & Forberg also worked to develop a protective, “modular sytem” of vitrine-containers for both transporting and exhibiting great art in climate-controlled splendor. Damien Hirst would love them. From an exhaustively transcribed October 1971 account in the Washington Post:

To nurture and protect paintings, Nelson and Forberg came up with something new. Using the language of the aerospace technology which created it they call it “a picture life-support capsule.”

…

It is a box about the size of a U-Haul-It trailer (14 by 8 feet) only skinnier (2 feet). It hums like a refrigerator and a Long Island aerospace company, Convectron, Inc., made it.

Holy smokes, add another space-meets-art object to the must-replicate and exhibit list! Move over, Jan de Cock, because I am kicking it Nixon-style!

Ahem. The article was occasioned by a capsule proof-of-concept exhibition of 19th and 20th century American landscapes, titled “Wilderness,” which opened, ironically enough, at the museum which had to close a show of borrowed masterpieces because of utter climate control failure, the Corcoran Gallery, run at the time by Walter Hopps.

The other curatorial eminence involved was Douglas MacAgy, who at the time was head of the NEA’s exhibition programs. He explained to the Post how “advance men,” a literal Art Fleet “avant garde,” would

“work out the logistics” of setting up the bubble clusters, and go around the community to schools, community centers, (whoever would listen), giving educational lectures about the exhibits themselves. Hopefully local people would want to lend their talents, and the high school band, the little theater, could perform in or near a dome.

That was the concept, anyway. Nelson actually called it “a circus of the arts. An art museum shouldn’t be a cross between a major psychological depression and a death in the family.”

Apparently it still needed work. Straight [who didn’t mention Nelson, Hopps, MacAgy, or the Corcoran show at all in his account], picks back up in April 1972, when Nelson & Forberg were coming back with revisions:

The designers, as Bill Lacy said, had grappled with the problem of bringing the Mona Lisa to every hamlet and, at the same time, protecting it from every conceivable danger. In Lacy’s words, “What they’d come up with was a rather unattractive merger between an ice box and an iron lung in which a great painting would reside. It was about that appealing to look at. We tried as best we could to regard it as a breakthrough but we knew that it would be greeted as a disaster. For, no one wanted to look at art in that way.”[p.150]

Ouch. In July of 1972, Hanks was supposedly looking for solutions for Art Fleet’s problems or a way to “junk it with good reason,” so Straight set up an advisory committee, which included the NGA’s J. Carter Brown.

[Brown] was patient, but the day came when he threw up his hands…Rather than attempting to transport great art to the people, he said, we should transport the people to our museums.

It was a direct hit. With that salvo, the indestructible trailer-trucks of Art Fleet and its impenetrable containers sank beneath the waves, like Victor Hugo’s mariners, never to be seen again.[ibid.]]

I’m sorry, I can’t resist Straight’s literary codas; he had a million of them. With Straight’s telling, Brown brought the Art Fleet to a swift demise, but it apparently it still took a while to chase the art circus out of town. Der Speigel had a very upbeat-sounding article in November March 1972 that sounds more like 1971. [1] [It’s also where I found that image of the model up top, with the awesome caption, “Kunst im Kanister.”] By October, when the 1972 NEA Annual Report came out, there was no mention of Art Fleet at all.

In 1975, Congress addressed the exhibition insurance problem by passing the Arts and Artifacts Indemnity Act, which gave the Federal Council on the Arts & Humanities the authority to offer museums and non-profits up to $1.2 billion of insurance for artwork loans. It’s not as sexy as Walter Hopps curating shows in domes on trucks, but it makes more sense.

I was eating dinner with Terry Riley in 1998, and we’d been talking about MoMA designing its new building in anticipation of accommodating Richard Serra’s sculptures, and how museums react and respond to art on an architectural timescale. It was right after SwissAir flight 111 crashed with several artworks, including a Picasso, onboard. And I remember him saying there had never been a major artwork lost in transit, but as soon as there was, the chilling effect on international loan exhibitions would be immediate and overwhelming. One result would be a shift to exhibitions that focus on conceptual, ephemeral, experiential, or otherwise non-irreplaceable art.

While the Mona Lisa/masterpiece fixation is obvious, after sitting on this post a while, I can’t help think how painting-centric the Art Fleet concept was. And it was brewing at exactly the moment [Six Years…from 1966 to 1972, as the book propping up my laptop right now tells me] where conceptualism was dematerializing the art object.

[1] So much, that I kept staring at it to make sure I hadn’t misread it. The Oct 1971 grouping of stories is clearly from a press event. But the Spiegel story does say 11/72. And then on another part of the page, I found “06.03.1972,” which is obviously March. So 11/72 is the issue number. So this all predates the advisory committee; so maybe Brown drove that Art Fleet right off the cliff before summer was over after all.