Joerg tweeted last night about a “[DESTROYED]” 1982 Gerhard Richter candle painting, and heeyeahsure, I’ll look at that.

It turns out though, that the artist’s own term is not entirely accurate. Because according to his website, the painting, 2 Candles 1982, (CR 499-3), still exists: “Richter painted over this work in 1996. The painting is now entitled Abstract Painting (CR 837-4).”

l: 2 Candles, 1982-96 state; r: Abstract Painting 837-4, 1996-, images via gerhard-richter.com

Which would be interesting enough if it were a one-off thing. And no, it appears that Richter has not painted over any of the 73 other paintings listed as “[DESTROYED]”. But by 1996, he had already been painting on photographs for a decade. In 1989, in fact, he produced two editions of candle images overpainted with squeegees.

Candle III, 1989, ed. of 30+10, image: gerhard-richter

There are at least a dozen other such editions since then which combine photos or photoreproductions and squeegeed abstract overpainting. They constitute a persistent connection between the two seemingly diametrically opposed bodies of Richters’ work: photo-based representation and so-called aleatoric, or mechanized, gestureless abstraction. It’s a dichotomy that continues to stump even the illustrious Benjamin Buchloh, who laments while writing, at great length, in the latest Artforum: “The question posed over and over again (and which has basically remained unanswered) was how these photographic images could be related to the emerging works of abstraction.”

But my bigger point here, which Buchloh also cursorily notes, as does anyone who’s seen Corinna Belz’s film Gerhard Richter Painting, is that overpainting is central to Richter’s abstract practice. In these stills from the scene that appears in Belz’s original trailer, Richter very thoughtfully creates classical gestural abstractions:

Which remind me of nothing so much as the great, underappreciated-until-just-now, large-scale paintings of Willem de Kooning from the mid-1970s.

It’s one of the main reasons I hustled back to MoMA to see the de Kooning show on the last day, after seeing Belz’s film, and after getting both the Richter and de Kooning catalogues for Christmas. Because these amazing wet-on-wet structures that Richter laid down

felt almost like reincarnations of some of the virtuoso brushstrokes de Kooning made in 1975 paintings like Screams of Children Come from Seagulls [check out this dark blue, sideways L from the upper right quadrant, for example]

or the single, epic loop at the center of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Untitled XI (1975):

And then when they’re just right, Richter takes his squeegee to them. As if getting erased by Rauschenberg wasn’t enough.

But–oh man, I really did just mean to do a quick, “ooh, look, overpainted Richter!” post here–but this is the thing that bugged me so bad about Buchloh’s reading: his extraordinarily limited range of references in discussing Richter’s work. I mean, it’s basically Johns and Stella [Stella!]. And he dismisses Johns on false pretenses. And doesn’t mention de Kooning once.

Here’s what Buchloh got from Belz’s film–WHICH HE WAS IN: some kind of Surrealist theatrical something or other:

Starting the production of each canvas with strange rehearsals of various forms of gestural abstraction, as though moving through recitals of its legacies, in the final phases Richter seems literally to execute the painting with a massive device that rakes paint across an apparently carefully planned and painted surface. Crisscrossing the canvas horizontally and vertically with this rather crude tool the artist accedes to a radical diminishment of tactile control and manual dexterity, suggesting that the erasure of painterly detail is as essential to the work’s production as the inscription of procedural traces. Thus an uncanny and deeply discomforting dialectic between enunciation and erasure occurs at the very core of the pictorial production process itself, opening up the insight that we might be witnessing a chasm of negation and destruction as much as the emergence of enchanting coloristic and structural vistas.

Alright, so maybe it’s not that wrong. No, it is, because after 20 years working on layers and layers of paint with that “crude tool,” Richter has proved, I think, that he has all the control he needs.

Just as Rauschenberg’s erasing were not negation, but creation through another type of mark, I think Richter’s squeegee strokes are generative additions to, not killers of, the rich repertoire of markmaking techniques he inherited. Maybe it took Belz’s film to show how tightly the squeegee marks are linked to Richter’s body and movement. They don’t diminish, but magnify; they’re full-body gestural abstraction.

For a great illumination of the specifics of Richter’s abstract production, I keep going back to Tate Modern conservator Rachel Parker’s discussion with blogger Mark Godfrey during the Panorama show:

If we think about the very large scale of Wald 3, we must consider the logistics of one man making this painting. Although Richter probably dragged the squeegee across the wet surface in two separate applications this process must have demanded enormous physical energy. The two resulting squeegee tracks are obvious: one track extends from the top to about 5/8 of the way down the painting surface and the other starts just below this. It would appear that Richter applies the squeegee first to the left side of the work and then drags it from left to right: with both tracks he appears to stop ¾ of the way across for a rest before completion. You can also tell exactly when the momentum of dragging the squeegee across the very tacky surface began to slow down as the drag marks become more shallow. The upper track is characterised by the squeegee having embedded itself more deeply into the paint resulting in slightly sharper surface disturbances and deeper excavations. The lower track has glided more fluidly across the surface creating lighter disturbances. There is undoubtedly an element of chance in the results of this technique: the first track will bear most influence on the final composition whereas with the second track, Richter tries to replicate the same direction, speed and weight behind the squeegee to re-create the same marks in the paint. The compositional balance between track 1 and track 2 in Wald 3 exposes Richter’s trust in his materials and intuitive craftsmanship.

I’ve got more bone to pick with Buchloh’s analysis, which ultimately fails to convince because it seems so disengaged, so cut off within the hermetic, Richterworld bubble. But maybe later.

Because Parker and Godfrey make a very persuasive case, I think, for some of the implications of Richter’s overpainting,. In this case, they discussed SFMOMA’s 1999 Abstract Painting (CR 858-6) [above] on aludibond panel:

Richter has applied his paint in a similar manner as before, manipulating the paint with a squeegee when the paint is very newly applied, hence its fluid character…Once the paint has dried Richter has taken a sharp wide-head palette knife and gouged and scraped features out of the paint layer, exposing the paint-stained white preparatory layer beneath. The technique creates a hallucinatory effect (are the shapes portals or are they solid elements floating in a multi-dimensional composition?).

These underlying paintings aren’t destroyed; they just become something else.

UPDATE: Alright, I’m righter than I knew. There are at least three more overpainted paintings.

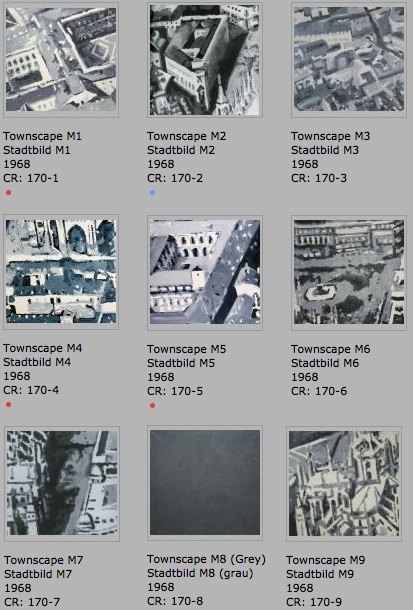

Stadtbild M1-M9, 1968, rearranged into a 3×3 grid, image: gerhard-richter.com

The earliest known example is from the Stadtbild/Townscape series, from 1968. Richter first created a large, 2.7m x 2.7m painting based on an aerial photograph of the center of Milan, which he then cut into nine nearly square paintings, numbered M1-M9. Townscape M8, however, he painted over with grey [above]. Joe Hage, the collector/technologist/uber-groupie behind Richter’s website notes:

Townscape M8 depicted what was presumably a detail taken from the same source photograph and was painted over with grey paint later.

…

The series Townscapes M1 up to M9 illustrates Gerhard Richter’s engagement in the process of abstraction: starting from a concrete depiction, which was enlarged at first and then cropped, the final image can barely be traced back to the source photograph. The numbering of the single parts of the painting, which do not relate in any way to their initial positions in the original large format, also suggests that any kind of identification is less important to Richter than the painterly process of abstraction.

So in this case, at least, there is currently only the presumption of underpainting, based on the series, the title, and the procedure of its making.

Hanged and Blanket, both 1988, via gerhard-richter.com

The next example, though, is the opposite. While painting his October 18, 1977 series in 1988, Richter made two identically sized versions of Hanged [above, left], only to partially paint over one and retitle it, Blanket, after the blurred photo-based image that remains visible under the squeegee. The CR numbers show that Blanket [680-3] was completed some time after Hanged [668], with at least two dozen squeegee paintings in between [including two “[Destroyed]” works]. After evoking the “function of a curtain in art history: a painted curtain indicates that a glance is allowed at something that should not necessarily be seen,” Hage’s note offers an interpretation of this overpainting: “It appears almost as if Richter wanted to shield the events from view, by painting over the second version of the painting almost completely.” Which would be true enough in isolation, but which seems to mean not considering the existence of the un-squeegeed version. Which is nevertheless blurred, as if there’s a continuum of obscuring and revelation.

The third example comes from the Spiegel story on Richter’s destroyed paintings. Ulrike Knöfel writes of a work

painted in 1990 [which] shows two young people standing in front of Madrid’s Museo del Prado, Spain’s national art museum. However, two years later, he painted over this work, turning “Prado, Madrid” into “Abstract Painting, 1992.”

There’s no Prado related work mentioned on the side, but there are two Atlas pages of photos from Madrid. I’m still looking through the 279 108 abstract paintings from 1992 to see if I can figure out which one it is. update from a few minutes later: no idea.