I ended up not bidding on anything in the David Rockefeller auction this week, but I had my eye on some things. At first I thought of the trio of simple, mismatched, 18th century Chippendale side chairs, which could round out a small table where a similar, orphaned family chair might one day need some company.

These nice but unremarkable chairs would go nicely with our humble chair, I thought, but claiming that is the reason to buy them would be a lie. You would buy them–I would buy them–because 65 years ago, the family registrar marked two of the three chairs with inventory numbers: D.R. 53.1758. I am fine with acknowledging this.

I realized that buying something you might conceivably need would violate the spirit of the occasion. Beyond all other auctions, a Rockefeller Auction is pure want. And what is wanted, above all, is provenance.

Could provenance and its auratic power be isolated from the object that is its ostensible vehicle? What object might make that possible? It would not just have to be non-precious, or non-aesthetic; it would almost have to thwart value and appeal. It couldn’t be ironic or sentimental, or hold even a remote association with Rockefeller personally–which seemed a little intrusive–or with the family and their history and legacy.

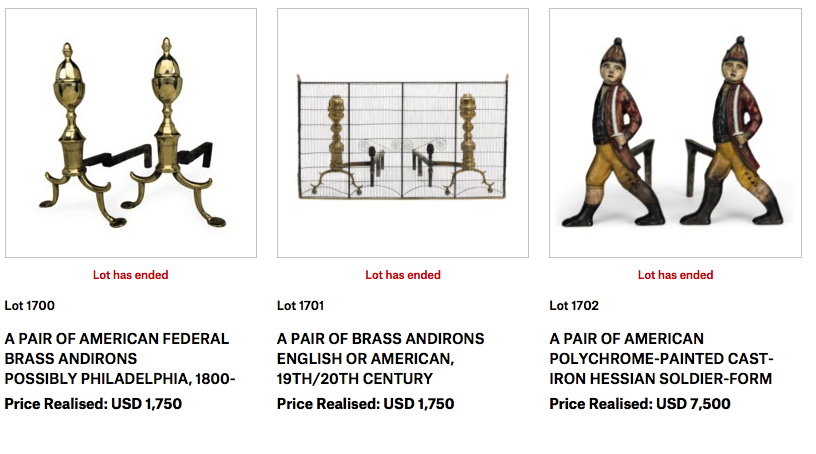

I love that this puzzle presented itself at the exact same time I was dealing with the Japanese plates Danh Vo bought 11 years ago from the rural Pennsylvania estate sale of an obscure US general with a connection to the Vietnam War and the JFK assassination. Anyway, I did a reverse estimate sort on the 800 or whatever lots in the online auction. I skipped past all the Staffordshire porcelain figurines of shepherdesses. I lingered for a moment over the fireplace tools and andirons (above). I have a thing for andirons of provenance, but then I remembered that the Rockefellers did, too: David’s brother Nelson had a business selling reproductions of his art collection, including his Diego Giacometti andirons.

Anyway, I did a reverse estimate sort on the 800 or whatever lots in the online auction. I skipped past all the Staffordshire porcelain figurines of shepherdesses. I lingered for a moment over the fireplace tools and andirons (above). I have a thing for andirons of provenance, but then I remembered that the Rockefellers did, too: David’s brother Nelson had a business selling reproductions of his art collection, including his Diego Giacometti andirons.

Then I found it: Lot 1732 An 18th Century English Cast-Iron Fireback, est. $200-400. It was in terrible condition, or rather, it had a rare patina. Like how they gratuitously leave the bird’s nest in the hood scoop of the barn find Ferrari. 1st Dibs lists two nearly identical firebacks [below] with Spes, the Roman goddess of hope, as 17th century Dutch, so Christie’s (and the Rockefellers’) description probably stems from the careful preservation of an inaccurate invoice “from WM. Jackson Co., 1 February 1956.” #provenance.

Oh, weird, what’s this, Lot 1753, Late 17th Century Italian Priedieu, “the base reduced in depth”, est. $400-600? A priedieu with the prie removed is kind of perfect. Not to question the Rockefellers’ faith, of course, just that when you put it in a home, the kneeling part of a priedieu can be a real tripping hazard. The provenance here was distinct, too: “Acquired with the contents of Hudson Pines.” David & Peggy bought Hudson Pines from his sister Babs, who’d built it. So this 10-inch deep, chopped up priedieu has a double Rockefeller provenance. I imagine it holding a tiny key bowl, or blocking an unsightly vent.

But it’s also almost the same dimensions as the fireback. Now I could see these two damaged, useless, clunky antiques together, a found monochrome diptych monument to this liquidity event, a celebration of the massive value accrued around them during the last 70 years of their 350 year existence.

Each of these marred tchotchkes ended up selling for $3000, which answers the question of what provenance is worth. And I don’t have to worry about where to put them.