America’s imprisonment of its own citizens because of racial bigotry during World War II has been of great interest to me since discovering Born Free and Equal, Ansel Adams’ self-published photobook of Japanese Americans detained at Manzanar, in the early 1990s. It always felt like important history that must be faced and not forgotten. Now, of course, it is a crime being surpassed and magnified, with families being torn apart and children fleeing for their lives being subject to state-sponsored terror at a scale this country hasn’t seen in almost a century, and all for the accumulation of Mautocratic political power.

It is not a sufficient response by any measure, but I am republishing a series of blog posts here which I made over the years at Daddy Types, the weblog for new dads, which I ran from 2004 until my CMS broke late last year. On DT I often wrote about the overlooked or forgotten histories and objects of parenting, with a focus on modernism, design, DIY, and dad-related projects. That included frequent posts on the material lives of Japanese American children imprisoned in detention camps during WWII, including the attempts to provide kids an approximation of a normal environment through schools, playgrounds, and domestic spaces built out of scrap lumber.

Here they are in chronological order. The first is a January 2009 post on the pre-school and playground at Topaz Internment Camp outside Delta, Utah. [2009 is when I learned my grandfather had helped build the Topaz detention center as part of the CCC.]

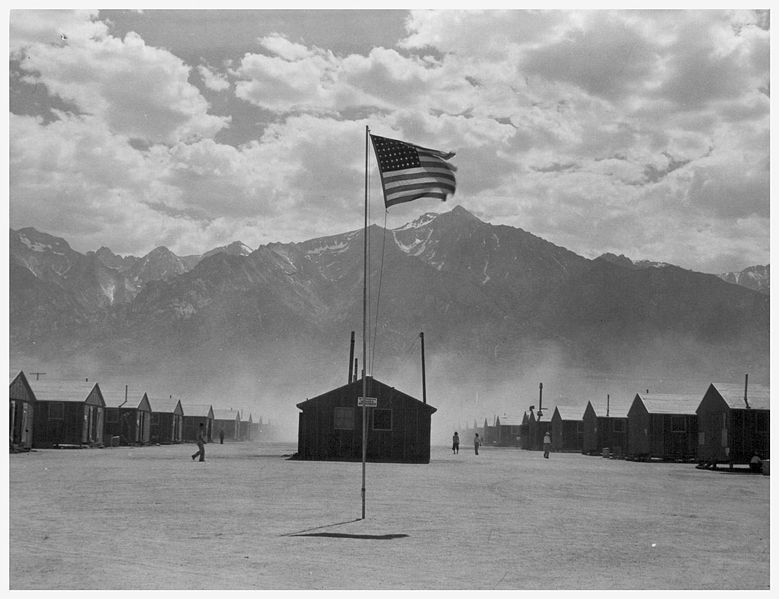

The Central Utah Relocation Center near Delta was later renamed Topaz Camp, after Topaz Mountain, which loomed over it to the west. When it opened on Sept. 11, 1942, several rows of tarpaper barracks had been finished and outfitted with an Army cot, a coal stove, and a lamp. The 8,000-plus Bay Area Japanese Americans who’d been stripped of their property and possessions and shipped to the middle of the BF Utah desert were left to build their own schools, churches, and furniture out of scrapwood.

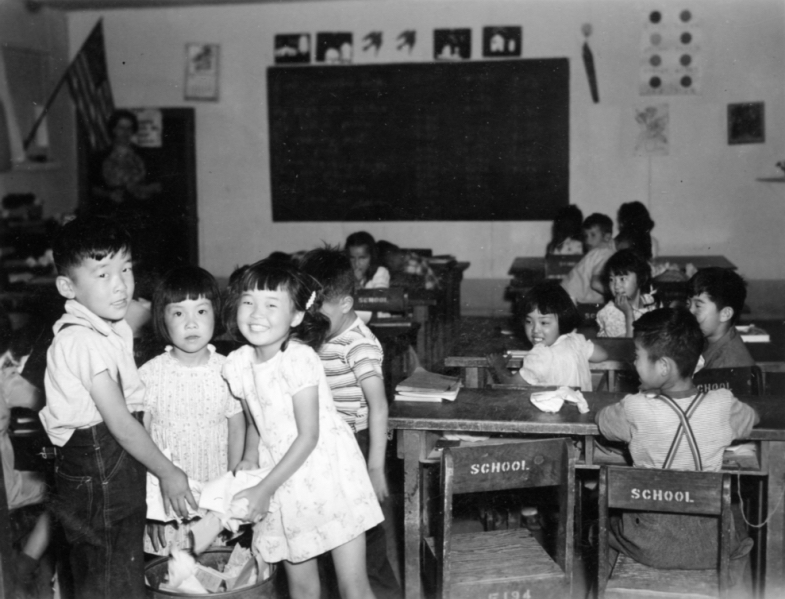

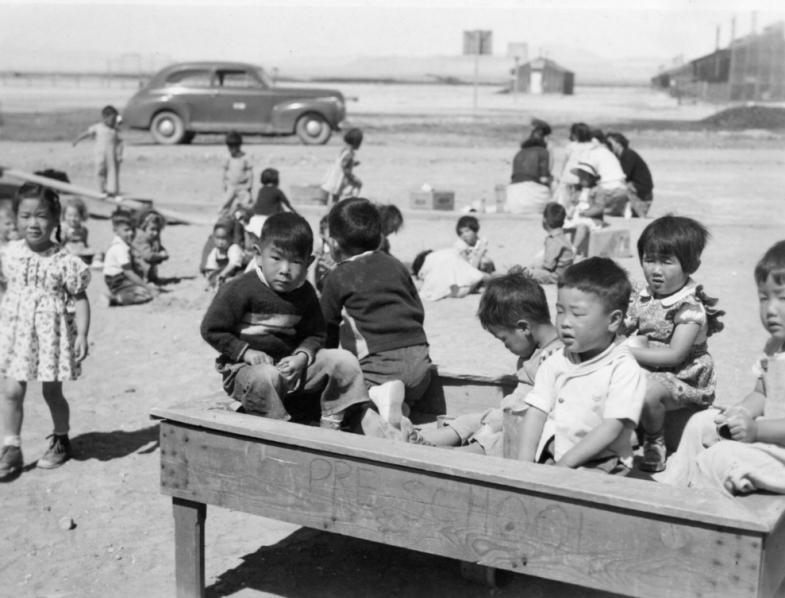

Common areas in the barracks were often repurposed into co-op stores and pre-schools. All the furniture, easels, and playground equipment seen here in the photos of Eleanor Sekerak, an Anglo teacher who moved to Topaz from Washington, was made by the carpentry workshop in the camp.

The Topaz Museum, based in Delta, has preserved and restored a half-section of a dining hall, which had been sold to a local farmer and used as a shed for 50 years. Mrs Sekarak’s scrapbook photos and other images and documents from Topaz Museum collection are available for viewing at the University of Utah Library’s website.

My great-grandparents lived in Delta, but I never heard much talk of Topaz. Over Christmas, I found out that my grandfather on the other side of my family had actually worked building Topaz Camp. He was young, but would have had at least one, maybe two kids in 1942, and had to leave them and my grandmother behind somewhere that summer. Now I wonder if these sandboxes and stenciled school chairs were made from the wood he left behind.

Topaz Museum collection [lib.utah.edu]

Topaz Museum [topazmuseum.org]

Originally published on Jan. 9, 2009, on Daddy Types as DIY Pre-School and Playground, Topaz Internment Camp, Delta, Utah [daddytypes.com]