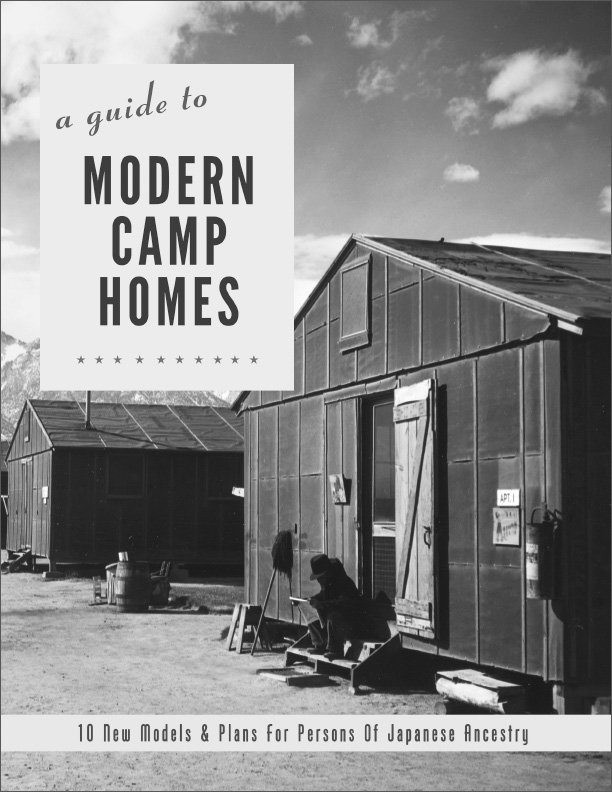

The whole thing was unexpected, tbqh, but one of the surprise bonuses of the Rabkin Foundation writers award situation was meeting artist/photographer Kevin J. Miyazaki when he came to make my portrait. I asked him to bring a copy of his 2013-and-counting artist book, A Guide to Modern Camp Homes.

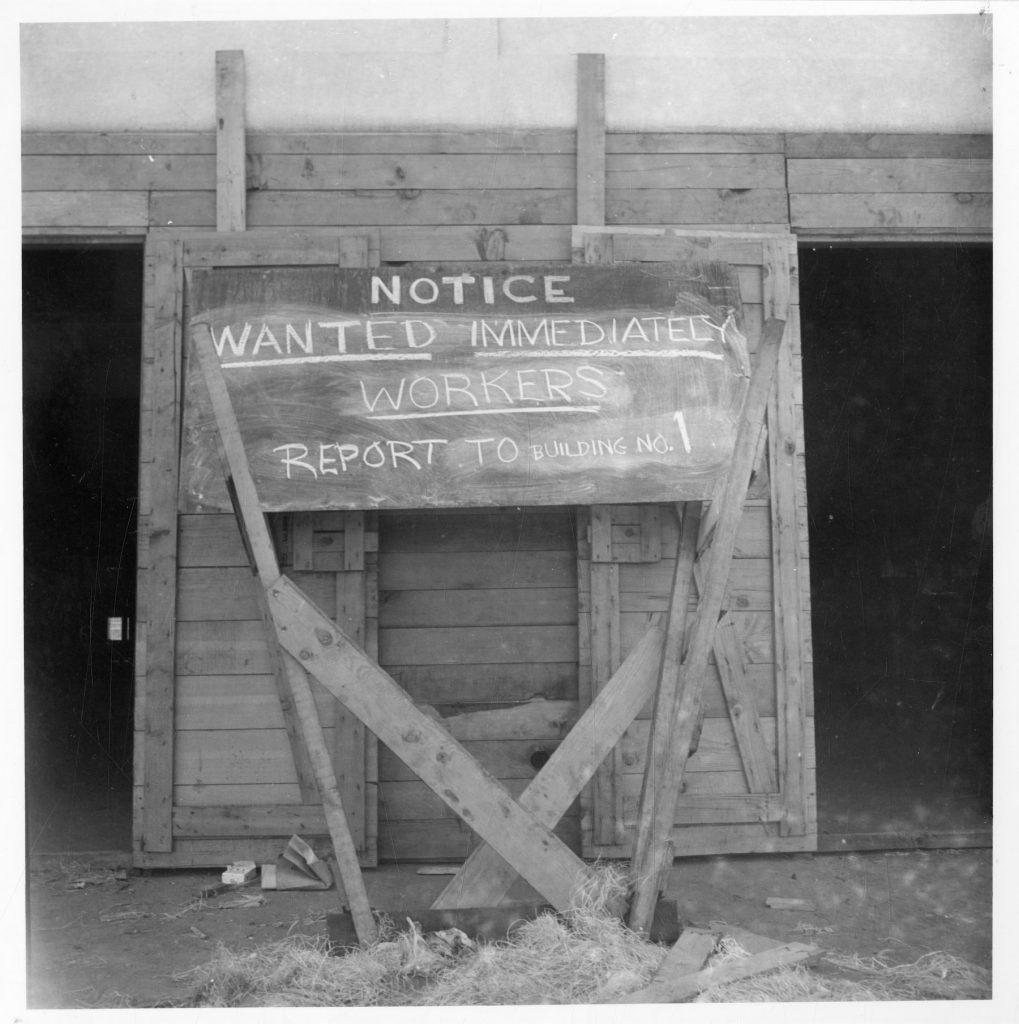

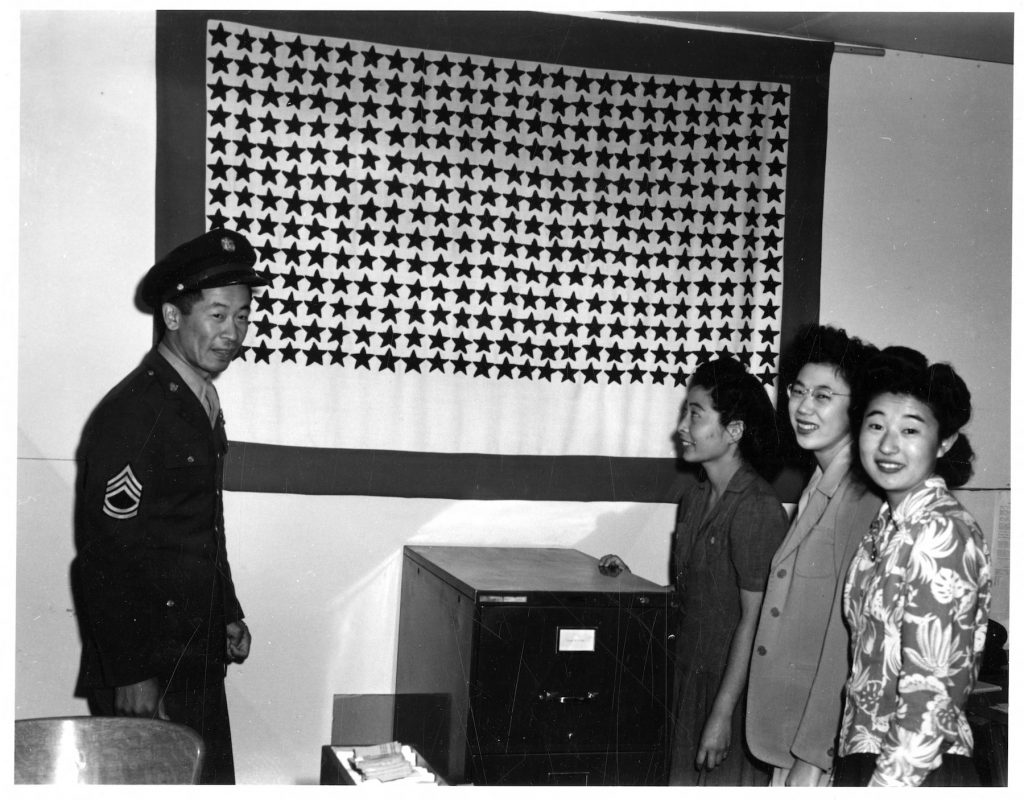

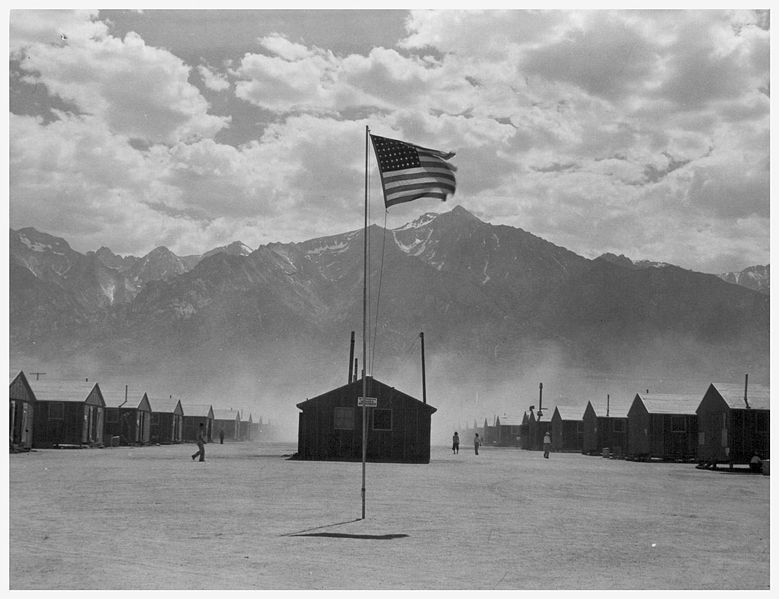

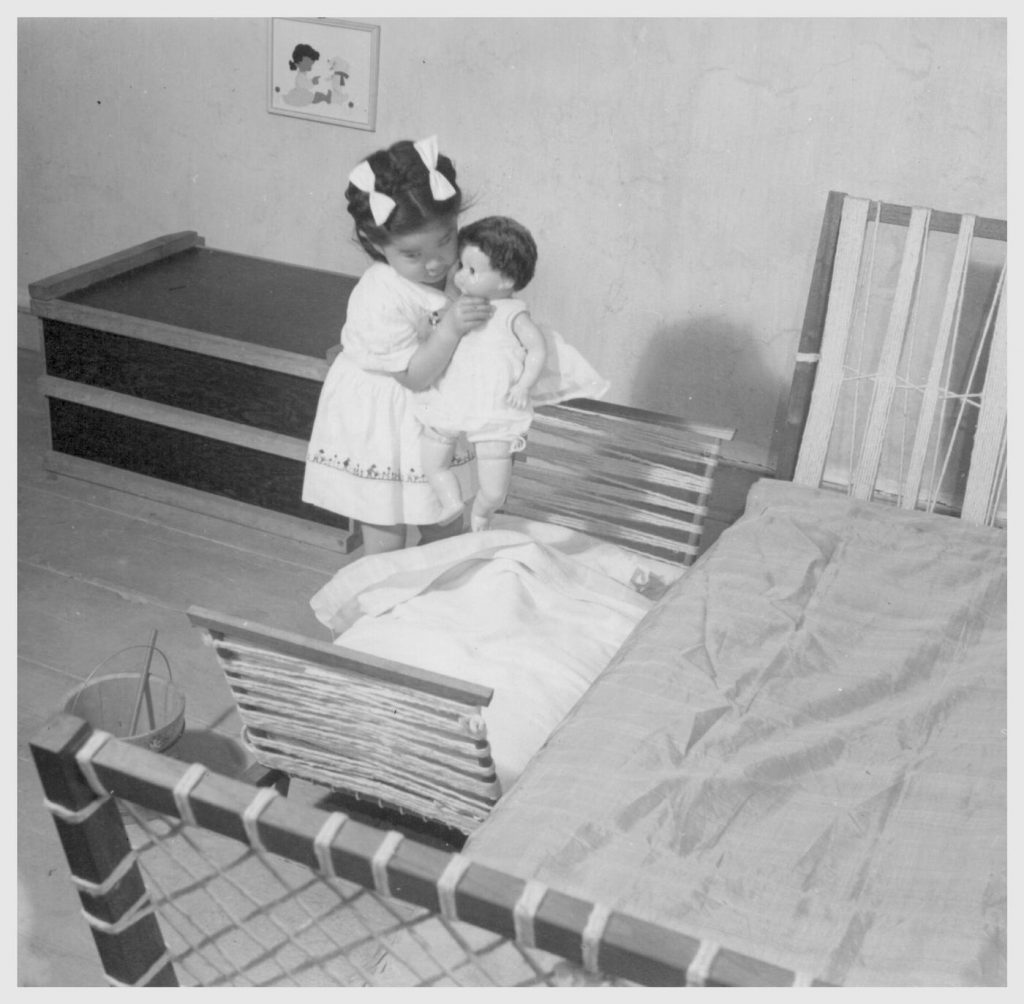

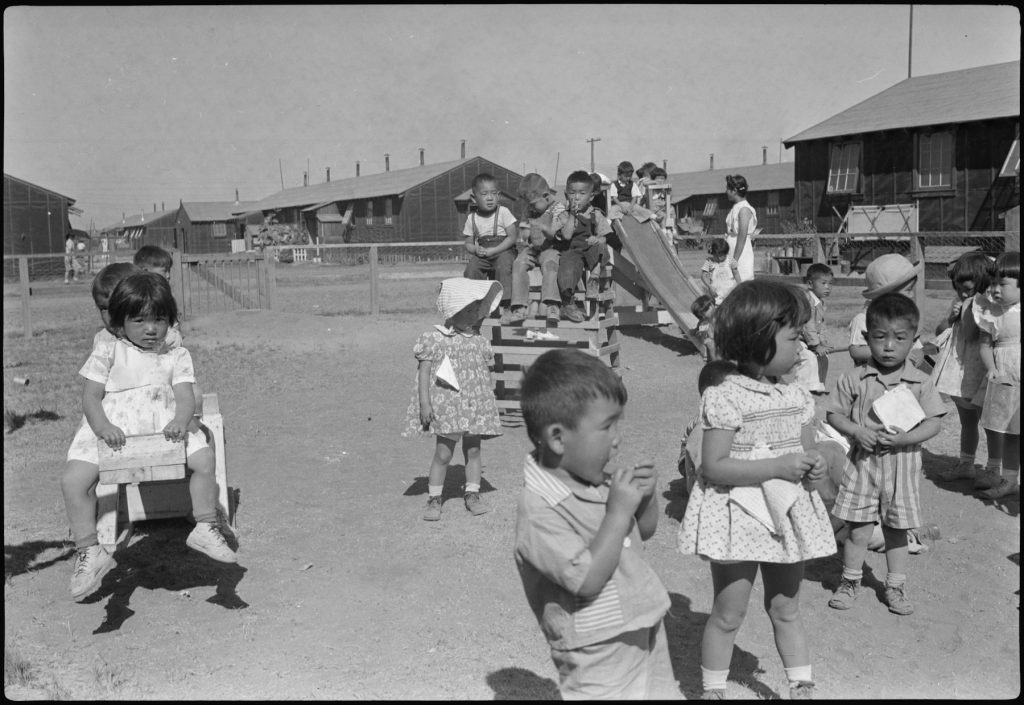

Modeled after Sears brochures for selling kit homes, Miyazaki’s Guide combines quotes from official notices and chirpy marketing with bright archival photos and renderings, as if racially segregated detention camps in the desert were the next step in the American Dream:

Customize Your Home

Your new home is unfurnished, aside from your bed frames, mattresses, and stove. You may wish to customize it with room partitions made from hanging sheets, and optional handmade items such as chairs, tables, shelves and window curtains. At some centers, large piles of discarded, green wood may remain from the home building process…

Where Sears would have run blurbs from satisfied customers, Miyazaki quotes the testimonies of former detainees, firsthand accounts of the sort gathered by Densho. In 2013 when he first conceived the Guide, I imagine the juxtaposition of deadpan form and horrible content was meant to foster a meaningful reflection on the wrongs that had been perpetrated by the US government against its own citizens.

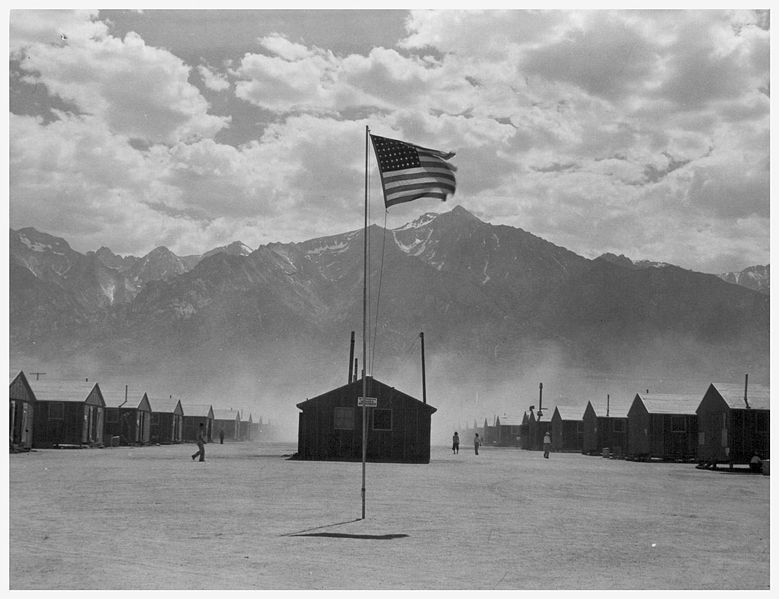

The next dates on the Guide, though, are 2017 and 2024, when Muslim bans; refugee children imprisoned and separated from their families; genocide; and campaign promises of industrial-scale detentions and deportations were back. And the guy behind it all just compared the jail sentences of the rioters convicted in the 2021 coup attempt to the WWII detention of 120,000 Japanese Americans.

And so now Miyazaki’s Guide functions, not as a gentle appreciation of the experience of the artist’s family and the Japanese American community, but as evidence in itself. That even just a few years ago, we held the truths of the deep, unjust, racist, violations of peoples’ fundamental rights and liberties to be self-evident, and that was reason enough to never let them happen again.

Read Kevin J. Miyazaki’s A Guide to Modern Camp Homes [kevinmiyazaki.com]

Previously, related:

2003: I mean, just look how happy they were!

2010: Ansel Adams’ Japanese American Internment Camp Photos at MoMA [Shhh!]

2011: I Am An American

2015/18: A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 6/X

My grandfather was a teacher in central Utah and volunteered to help teach the children there. He was appalled that these good people were interned (imprisoned) and admired them for how hard working and intelligent they were, and also for the patriotism to put up with this. I never knew this until I read his journal after he passed.

Ironically, he was a German immigrant whose travel to America was sponsored and encouraged by his Jewish employers who seeing the infant Nazi movement told him that if they were his age they would go to America.

They lent him the money on his word that he’d pay them back, which he did. I don’t know what happened to them.

Back to Topaz, that place is literally in the middle of nowhere desert.

[Originally published on Daddy Types on March 29, 2013, as Topaz Mountain Sleds by Dave Tatsuno and Bill Fujita, with a relevant comment included here.]