Two years after her retrospective in Frankfurt, Cady Noland has opened a show in New York that includes new work. It is in support of The Clip-On Method, a new, 2-volume publication of her work and writing, edited by Rhea Anastas. The title calls to mind Clip-On Man, a 1989 print on aluminum work based on a Charles Gatewood photo of a wild-looking executive at Mardi Gras with multiple Budweiser six-pack rings clipped onto his belt.

The website announcing the book and show at Galerie Buchholz, states that, “Publishing photographs of the work of Cady Noland without the express permission of the artist will be viewed as copyright infringement.”

I have not seen the show in person yet, so this post is based on viewing many infringements on Instagram in the three days since the show’s unannounced opening.

The show includes three silkscreen on metal panels, framed, from 1991/1992, and six new works, all untitled: two whose materials are listed as “Galvanized steel fence,” and four described as “Plastic barricades.” These forms offer a continuity with earlier works.

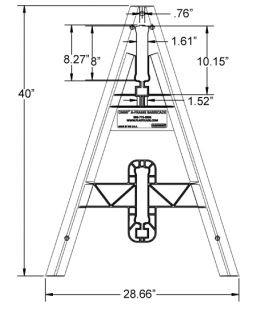

The plastic barricades are of the A-frame type, with slots for two 1×8″ rails. The edition titled, A Piece (1998), which these works most resemble, had only one rail slot. [For some reason, the MMK lists those barricades as “sawhorse blocks.”] Like A Piece, these apparently unique works have multiple, redundant legs racked and spread along a single rail. Unlike A Piece, the rails on these untitled works are not painted wood, but extruded plastic.

One barricade work with 16 frames, has the rail installed in the lower slot, because, I guess, now it can. The other three barricade works are shown in a former office space. Two with 15 and 23 frames, are side by side. The fourth is perpendicular, and six of its frames are exhibited beside the remaining eight, from which top slot the rail protrudes.

As someone who has tried over the years to identify from afar and source the A-frame legs from the 1998 works, which I saw in person at the time and have long regretted not buying, I feel attuned to the indexical aspects of the current examples. Whatever factors have driven the changes in injection-molded A-frame barricade design over the last 28 years, artistic consideration is not one of them. Without scouring through the entirety of Alibaba, I feel pretty confident in identifying these barricades as the Econocade™ Omni™ A-frame from the Plasticade division of the American Louver Company. [Unless? Because the rails on Noland’s sculptures lack the high-visibility orange striping of Plasticade’s product.]

The two chainlink fence-type works are of comparable size, probably 8×8 feet. They appear similar, except that one has a middle rail. The rails–top, bottom, and one middle–are connected by brace bands to two galvanized end posts by brace bands. The posts have no caps, and the bottom is inserted into the collar of a square footplate with four holes used to secure such posts to concrete. The chainlink fabric is finished knuckle-knuckle on the top and bottom selvedge, and is held taut by tension bars on each side, which are in turn held parallel to the posts by five tension braces on each side.

The chainlink work with a middle rail is similar to a 1994 work in the Frankfurt show, Not Yet Titled, which Bruce Hainley called a “massive, tilted chainlink ‘wall,'” [not sure whose quotes are around “wall”]. It is installed against the front window of the gallery, immediately to the right of the entrance. The chainlink work with no middle rail is flat against a wall, and up against the edge.

These four-sided, self-contained, fence-like objects are similar in composition to rolling gates, dog kennels, or the cages in which the US has been detaining children fleeing across the border since at least 2014.

It feels significant, though, that these are not readymades, found and recontextualized objects. As objects, they would be failures. An easily toppled, torqued, or circumvented fence. A barricade with 40 legs but only one rail. They are instead works composed and constructed from industrial materials, from components of industrial systems optimized to manufacture products that control the physical movement of human bodies.

The three earlier works are enlarged reproductions of annotated pages from Police Patrol: Tactics and Techniques, a 1971 textbook by Thomas Francis Adams. Like so much of Noland’s work, they feel more relevant than ever.

A charcoal carpet resembling wet asphalt covers the gallery’s parquet flooring, removing the only non-black/white/grey color from the show’s installation. After the euphoria of the availability of new work from a major artist subsides a bit, I wonder what it means that Noland is engaging some of the same forms and strategies she became known for. Is she looking back, or are these things she’s been engaged with all along? How do we engage with one of the most influential artists of the era, who makes an extremely rare exhibition of seemingly familiar work? Do we need to know how she arrived at these objects at this moment, or is it enough that they exist? To paraphrase Heraclitus, no artist shows in the same police state twice; for it is not the same police state, and she is not the same artist.

Cady Noland: The Clip-On Method, 17 June to 11 Sept 2021 [buchholz.de]

Buy The Clip-On Method [thecliponmethod.com]

Previously, related: Wait, What? Cady Noland, 2008?